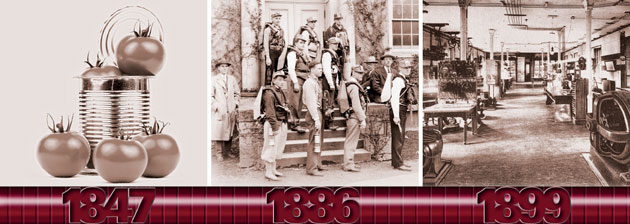

Engineering at Lafayette Spans 150 Years

by Bryan Hay

Every day, 20,000 vehicles cross the Northampton Street Bridge connecting Easton and Phillipsburg, tires on the metal deck producing a musical whir as people pass beneath golden finials, plaques, and gleaming reliefs of the Pennsylvania and New Jersey seals.

James Madison Porter III, who served on the engineering faculty from 1890 to 1917 and whose grandfather was one of the College’s founders, designed the majestic span, built in 1896 and known locally as the “free bridge.”

James Madison Porter III

His design is widely considered an engineering masterpiece, a pinned cantilever truss bridge with the sweeping lines and curves of a classic suspension bridge.

A disciplined union of science and the humanities, Porter’s design defines the Lafayette ideal, which was articulated on campus in 1866 with the arrival of the first civil engineering majors. They “set the goal of educating not just the engineer” but the whole person, who is then “able to meet the challenges of a world in which scientific, technological, and human needs have steadily become more complex.”

Now, in 2016, the world’s challenges and needs have become more complex than even Porter might have envisioned.

“We’re learning about tissue engineering and limb regeneration,” says Kyla Dewey ’18, a chemical engineering major. “I never imagined I’d be learning and discovering on this level.”

Laying the Foundation

By 1866, Lafayette College was prepared to add engineering—civil and mining engineering at first—to its offerings of majors. The Industrial Revolution was well underway, with the country eager to rebuild itself after the Civil War, says Professor Scott Hummel, the William A. Jeffers Director of the Engineering Division.

“The Civil War was a horrible conflict that fractured the nation,” he says. “Technical advances from the war used for the military got people thinking that it was time to use those technological advances for peaceful purposes to help people. And we’ve been doing that ever since here at Lafayette.”

Harrison Woodhull Crosby

The campus was becoming fertile ground for engineering as far back as 1837 with the offering of a basic course in mining. By 1841, the College’s catalog included the addition of a one semester offering of civil engineering.

By 1847, even the College’s chief gardener and assistant steward, Harrison Woodhull Crosby, investigated the possibilities of engineering by introducing the hermetically sealed tin can to preserve fruits and vegetables. Crosby canned stewed tomatoes, unfamiliar to American diets at the time, and sent six packs to President Polk, members of Congress, and Queen Victoria.

Illuminating the Future

Swept up by the electromagnetic advancements of Thomas Edison and Michael Faraday and the introduction of the telegraph in the Lehigh Valley, electrical engineering was introduced at Lafayette in 1899, just over a decade after the first use of electricity on campus in cooperation with Edison’s company. One of the first to enroll in the new electrical engineering curriculum was John Morton Davis, a great-grandson of John Morton, one of the Pennsylvania signers of the Declaration of Independence.

Courses in electrical engineering at Lafayette were initially part of the physics department and remained there until the major became part of the engineering department in 1909.

Edward Hart

Mechanical engineering was also introduced in 1899 with a $100,000 pledge from industrialist Andrew Carnegie. Although few students or members of the public knew about mechanical engineering at the time, its early development coincided with the era of the steam engine, the first Model T, and the Wright brothers’ glider. Faculty and staff at Lafayette understood that mechanical engineering would be needed to support the rising technology and innovations of the 20th century.

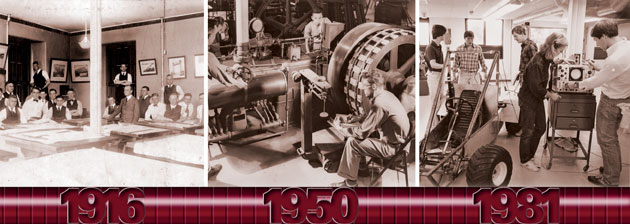

Recognizing the need for large-scale chemical facilities and an expansion in chemical engineering, Edward Hart brought chemical engineering to Lafayette in 1915. Hart saw the need for chemical engineers in America, and he connected the chemistry department and other engineering courses.

Technology for the People

Like the times and circumstances that inspired Lafayette’s engineering programs, this 150th anniversary year is another pivotal time for engineering, Hummel says.

With an 80 percent growth in enrollment in engineering majors over the last 20 years and a U.S. News & World Report list ranking Lafayette College among the top 15 engineering programs in the country, Hummel says, “we’re not going back down.” Lafayette placed 34th just a few years ago, ascending faster than any of the 250 schools ranked by the magazine.

“It’s all about the students,” he says. “From the moment they come to campus, it’s simply amazing to watch how their curiosity and enthusiasm for learning grows. When they leave Lafayette, they’re ready to make their mark.”

“Right now, especially with the anniversary, it feels like Lafayette College is on the cutting edge of teaching us about the newest technologies, like 3-D printing,” says Freddie Hess ’16, a mechanical engineering major.

Kyla Dewey is enjoying what she describes as “an amazing time of discovery,” particularly in her biomolecular engineering course with Lauren Anderson ’04, acting chair of the chemical engineering department.

Hummel is proud of the students and alumni he encounters. For that reason, he says, Lafayette needs to stay at the forefront of engineering, to inform, motivate, and drive people to discover and seek solutions for the common good.

“At Lafayette we’re changing the traditional view of engineering. The messaging that has surrounded the engineering profession for decades is that engineers are problem solvers and developers of technology,” he says. “While this is true, it doesn’t get to why, which is to help people. We’re changing the message of engineering from problem-centered to people-centered.

“Engineering should exist to help people live longer, happier lives, and develop technology to that end,” Hummel adds. “It’s up to the Lafayette College community to help society move forward.”

Norman Fortenberry, executive director of the American Society for Engineering Education, praises Lafayette for preparing engineering students for what lies ahead.

“Lafayette prepares engineering students to think beyond the purely technical to consider the social, economic, cultural, and political context in which their clients and end-user consumers live,” Fortenberry says.

In a nation where the fastest growing sectors of the economy are dominated by small- and medium-sized business, Fortenberry says the College’s engineering students excel because of their entrepreneurial mindsets.

“Lafayette exemplifies the integration of engineering with the liberal arts and provides the type of education needed to address the challenges of the 21st century,” he says.

Sustainable Suspension

To commemorate the 150th anniversary, a campus-wide competition is already bringing together students, alumni, and faculty in a friendly competition to build new bridges—in this case a large replica of Porter’s Northampton Street Bridge. In keeping with Lafayette’s commitment to sustainability and engineering principles, designs will be judged on the types of materials used and ease of assembly, as well as attention to the decorative touches used on the original bridge.

Members of the winning team will erect their free bridge on the Quad on Oct. 1 during homecoming weekend. Construction materials will be donated to a local charity after the model is taken down.

“Porter’s bridge is a symbol to rally around,” Hummel says. “Whether working on the model bridge competition or leading the way in the fields of energy, medicine, transportation, or communications, Lafayette engineers understand how curiosity, science, and the humanities combine to help them seek creative solutions.”