‘The Most Dramatic Thing I Ever Saw’

Jackie Robinson

Tom Villante ’49 remembers the man who shattered baseball’s color barrier, Jackie Robinson.

In the 1991 film Field of Dreams, long-dead baseball legends magically return to life in their prime to relive their game-playing glory days. But the magic only holds on the diamond. Once they cross the field’s gravel border, they can’t return.

That’s what happens to rookie “Moonlight” Graham. As he steps over the line, his cleats turn into wingtips, his uniform to a rumpled suit. His hair turns to frost, and he takes on the stooped posture of the aged doctor his future self becomes.

The message, seemingly, is when you’re part of a kid’s game, you’ll always be a kid. Maybe that explains Tom Villante ’49.

At age 88, Villante looks 30 years younger. He still has a head of dark hair, hits the golf course regularly, and splays his speech with rapid-fire anecdotes in his New York accent (think Joe Pesci on stimulants). Since World War II, he’s seldom strayed far from the game that owes him so much. Don’t scour through your card collection looking for a Villante; he never played a professional inning. But for the better part of the 20th century, Villante was a tall figure in the mists that surround the nation’s pastime, as important as some of the stars he called friends: DiMaggio, Berra, Robinson. Those stars are all gone now, but Villante still tells their stories from his home in Westchester, N.Y. He churns out an email newsletter called Me and Alphonse from a state-of-the-art computer. The newsletter is named for Alphonse Normandia, the mustachioed art director from BBDO, the ad agency where Villante started his career.

The room’s large windows draw light from the sun-dappled Westchester Country Club, Villante’s home for much of the past decade. Until recently, Ralph Branca, Villante’s longtime pal, lived one floor up. Branca was the Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher who gave up the famous Shot Heard ’Round the World to the New York Giants Bobby Thomson on Oct. 3, 1951. (For the baseball uninitiated, that’s the game where commentator Russ Hodges’ call—“THE GIANTS WIN THE PENNANT! THE GIANTS WIN THE PENNANT!”—came into being.)

“If I had a do-over, I would have thrown him a knockdown pitch,” Branca once told Villante, “then struck him out.”

Branca had been an usher at Villante’s wedding. He died Nov. 23, 2016, at 90 years old.

In the days that followed, Villante sent out three editions of Me and Alphonse, each about Ralphie. One was about the time they met actor Peter Falk on the streets of New York. Another was the story of Bobby Thomson’s shot. The third was a conversation about an aging Branca at a Dodgers fantasy camp in Vero Beach, Fla. Branca, with two bad knees, is sitting with a group of former Brooklyn Dodgers, each with ailments of his own. Branca gets up. Slowly, gingerly, he walks away from his circle of friends.

“Hey, Ralph,” yells center fielder Duke Snider, “where are you rushing to?”

Villante is curator of a wealth of baseball stories. Many of them collide in layers; a Villante anecdote might begin during World War II, but the punchline doesn’t arrive until the Reagan administration. Often, they swerve into unexpected cul-de-sacs. Stories can start in a locker room and end up in a fancy hotel with Jimmy Stewart.

All of it is “terrific.” That’s Villante’s go-to adjective. It’s a fitting one for a life that through energy, instinct, and spectacular luck created a charmed labyrinth of Americana.

Before you step inside, remember two things.

Villante lived baseball’s golden age.

And he owes it all to the New York State Regents Examination.

In October 1943, Villante’s buddy, Chester Palmieri, a ball boy for the New York Yankees, was studying for his Regents, standardized exams required by New York state for all college-bound students.

The boys hailed from Jackson Heights, the populous working-class neighborhood in northwestern Queens. They palled around with a young Don Rickles. They played sandlot ball in the nameless collection of ramshackle diamonds that fanned around Queens in those days. Villante was also a scrappy little shortstop for the Stuyvesant High School team.

Palmieri’s ball-boy job with the Yankees was a chance to get closer to the game. From time to time, Villante went with him to Yankee Stadium in the Bronx to help out and see Major Leaguers up close.

During the 1943 Yankees-St. Louis Cardinals World Series, Villante asked Palmieri if he could go with him to the ballpark.

“I can’t,” Palmieri said. “I have to study for my Regents exam.”

“You’re kidding,” Villante said. “Can I go in your place?”

All of it is “terrific.” That’s Villante’s go-to adjective. It’s a fitting one for a life that through energy, instinct, and spectacular luck created a charmed labyrinth of Americana.

So that day, Villante struck out for Yankee Stadium alone. To hear his story today in the era of security checks and metal detectors, Villante’s World Series entrance sounds magical.

He walked in through the players’ entrance. No one stopped him.

He wandered into the clubhouse, unimpeded. Villante told a man there he’d come to fill in for Palmieri.

“All right,” the man said. “Go to the Cardinals, the visiting clubhouse, and get them to give you a uniform.”

It was a mistake. Palmieri wasn’t a team batboy, he was a ball boy and for the Yankees–one of the kids who fields balls in foul territory and chucks them up as souvenirs into spectators’ hands. Ball boys hung out on the sidelines and weren’t much better than the average schmo in the bleachers eating a hot dog.

Team batboys were different. Villante found himself suiting up in a big league uniform, sitting in the dugout inches from the likes of Stan “The Man” Musial, and handling actual big league lumber.

So, for all three Yankee Stadium World Series Games from Oct. 5, 1943 to Oct. 7, 1943, Villante wore a Cardinal uniform and handed out big league bats. His Yankees won, even minus Joltin’ Joe DiMaggio, who’d gone with several other Yankee phenoms to do their bit in the military for World War II.

A week after the World Series, Villante decided to see if he could make it a permanent gig. He went back to Yankee Stadium. He waited outside until he again bumped into that clubhouse angel who’d given him the assignment. It was Fred “Pop” Logan, the Yankee custodian since the team first moved to New York as the Highlanders in 1903. Villante asked him about a job.

“Just a minute,” Logan said and went inside.

Moments later, a broad-faced man came out. He smoked a cigar. Slowly, Villante realized it was the legendary Yankees manager Joe McCarthy.

McCarthy asked Villante where he went to school and whether he had afternoons free.

“Would you like to be the home team batboy?” McCarthy asked.

“I’d love it,” he said.

So in 1944, Villante got his big break.

He never heard from Palmieri after high school. Once he tried looking up the name on his computer. He found an orthodontist in Rockville Centre.

Seventy-two years later, Villante has no idea how well Palmieri did on his Regents exam.

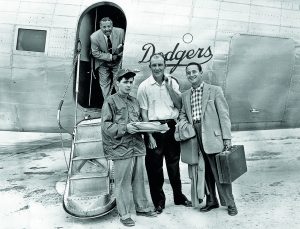

Villante (right) was a producer for the Brooklyn Dodgers in the early days of televised baseball.

At the time, the Yankees shortstop was a 33-year-old named Frank Crosetti. “He was like my mentor,” Villante says. During practice, Crosetti helped the kid with his fielding. At a big league ballpark, Villante found that throwing from shortstop to first base was like heaving the ball a mile. Crosetti recommended Villante move to second base.

Crosetti and second baseman George Stirnweiss must have liked what they saw, because the Yankees started to season their batboy as a player. They taught him to turn double plays and hit from both sides of the plate.

Other clubs began to take notice, as well. Lou Boudreau, the shortstop-manager of the Cleveland Indians, called him one day. He suggested Villante consider attending college at his alma mater, Northwestern University.

The next day, the Yankees’ McCarthy called Villante into his office. “Have you been talking to Mr. Boudreau? What did he offer you?”

“University of Northwestern,” Villante said.

McCarthy shook his head. “You pick out the college. We’ll send you.”

Villante’s cousin, Tony Labate ’31, lived in Easton and attended Lafayette. So did his brothers. They were doctors and lawyers.

It was 1945. Villante respected the new Lafayette coach Charlie Gelbert. The Yankees, who had promised to help him pay for Lafayette because of Lou Boudreau, anted up for room, board, and books. Villante received the William P. Coughlin Scholarship. (Coughlin had been a Lafayette Leopard coach for 23 years and a third baseman for the Detroit Tigers.) He played basketball, baseball, and as part of the deal, he worked out summers with the Yankees—still a top prospect to be the team’s second baseman.

World War II was just ending. The school was loaded with returning GIs or guys like Villante, who’d been too young to serve. They all shared an expression: Stay loose. “Everyone was always going around saying, ‘Stay loose, stay loose,’” Villante says.

So he wrote about sports for The Lafayette student newspaper, which had just restarted publication after pausing for the war, creating a fictional character by reversing the letters in Stay Loose as YATS ESOOL. “We had a lot of fun,” Villante says. “All these returning veterans got a big kick out of him.”

It was his first taste of sports media, he says.

One day in the spring of 1950 as Villante was working out with the Yankees, a fiery ballplayer came out onto the field and said, “I’m going to play second. You play shortstop.”

It was Billy Martin. Martin was the Yankees starting second baseman for seven seasons, an All Star in 1956, and won five World Series with the team as a player and a manager. In 1986, the Yankees retired his number.

Although Villante wound up befriending Martin, his playing days were done. Instead, he followed the fortunes of YATS ESOOL, which helped him land a job with New York ad agency BBDO.

It was the age of Mad Men, the AMC TV show about advertising men in the 1950s and 1960s and the lives they led. Villante’s BBDO was one of the models for the show. “Everybody smoked, no question,” Villante says. He felt the Mad Men characters’ alcohol guzzling was overdone and as for the extramarital affairs—“who knows?”

Villante had landed a job in BBDO’s public relations department. By the time he’d left Lafayette, he’d begun doing sports publicity work. (That iconic photo of Leopard hoopster Marty Zippel holding a basketball with 1001 on it, denoting his 1,001st point? Villante was the guy who did the math.)

The Brooklyn Dodgers were a BBDO concern. In 1952, Lucky Strikes cigarettes and Schaefer Beer split the entire Dodgers team sponsorship. So much money was involved that BBDO brass felt they needed a staffer from the agency to produce radio and TV broadcasts and the job should go to someone with sports knowledge. Someone who spoke the lingo and knew the guys. A certain former Yankee batboy.

“I knew nothing about radio or TV,” Villante says. “It was the pioneer days of television and nobody knew anything.”

But Villante had majored in electrical engineering at Lafayette; he knew about coaxial cables—knowledge that came in handy from time to time. He produced games in Brooklyn from 1952 to 1957. When the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles in 1958, he moved out to the West Coast with the team. He’s the only one who worked with both long-time Dodger commentator Vin Scully, who retired in 2016, and the legendary play-by-play man William “Red” Barber, who called the Dodgers games from 1939 to 1953.

One day, Villante’s own television set went on the blink. He called a repairman. “He wanted to charge me $30!” he says. “Ridiculous.”

After all, Villante had an electrical engineering degree. He opened the back of the TV. “It was all vacuum tubes in those days,” he says. He replaced the tube for about 50 cents.

After fixing the problem, Villante gave the inner workings of the box some thought. He knew enough, he figured, to help other people with most TV problems.

So he wrote a book. TV Cure, he called it.

“It made enough to buy a boat,” he says.

“I knew nothing about radio or TV. It was the pioneer days of television and nobody knew anything,” says Villante (top row, far left), shown here in 1954 with legendary broadcasters. Front row (from left) Vin Scully, Connie Desmond, Al Hefler. Back row (from left) Villante, Red Barber, Mel Allen, Joe Ripley.

Advertising, baseball, and Tom Villante evolved together.

But during the 1960s, as Villante was becoming a bigger name in the business, baseball was losing steam. Professional football with its faster pace and TV-ready style was eating into the national past time’s market share.

In 1969, Major League Baseball brass put the sport under the knife, restructuring the leagues and altering some of its rules. At the same time, the professional sport celebrated its centennial, which seemed tailor-made for a marketing coup to reenergize. E. Michael Burke, Yankees president and CEO, asked the old Yankee batboy to quit his job at BBDO and work for baseball full time. Villante refused, but took Major League Baseball on as a client and handled the centennial.

He created the “Greatest Players Ever” promotion and welcomed the biggest collection of living baseball heroes to a gala celebration at the Sheraton Hotel in Washington, D.C. To commemorate the anniversary, baseball held its All-Star Game in Washington, produced a baseball-themed U.S. postage stamp, and created the Major League Baseball logo still in place today.

Less than a decade later, Villante finally jumped ship from BBDO and went to work as executive vice president of marketing and broadcasting for Major League Baseball. One of the first orders of business: Who are these baseball fans, anyway?

Market research determined that fans were mostly guys, high school educated and blue collar. “He’s watching the game on TV or listening on radio,” Villante says. “So the objective was how do we convert 15 percent of that listening audience to come out to the ballpark? … You can watch it on television, but something happens when you’re there at a game. You’re there with other people. You get caught up in the emotion, the excitement. It’s contagious.

Among Villante’s most recognizable creations, “Baseball Fever: Catch It” was everywhere in the late 1970s.

“That’s where ‘Baseball Fever: Catch It.’ comes from.”

It was Villante’s slogan. You saw it everywhere during the late 1970s and early 1980s. The ads were simple: highlights from the game with the words superimposed.

It was the sport’s first ad campaign.

Did it work? According to baseballprostpectus.com, average ballpark attendance was stagnant at about 1.2 million from 1969 to 1977. By 1983, it had risen to 1.7 million and continued ever upward. In 2016, it was more than 2 million.

All those butts in the seats didn’t come from Villante, but his slogan and ad campaign were the first steps toward repopularizing the game.

In 1984, Villante struck out on his own. He launched Tom Villante Sports Marketing, continuing to produce spots drawing on his creative enthusiasm, baseball connections, and long memory.

Like this one: It was September 1946. Villante was on his break from Lafayette working out with the Yankees. One day, there was a commotion around one of the lockers.

“What’s going on?” Villante asked Joe DiMaggio.

“There’s this rookie we just brought up,” DiMaggio answered. “He’s kind of funny.”

Villante listened to the guy and cracked up. The rookie had a silly way of telling a story that was simultaneously inane and ingenious. He was talking about a movie he’d seen the night before.

“His name is Yogi Berra,” DiMaggio told him. “He’s a character.”

Villante carried that story with him for more than four decades before he figured out a way to use it.

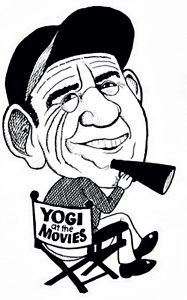

“I says, ‘You know, as a way to break through the clutter I’m going to have Yogi the movie critic and call it ‘Yogi at the Movies.’”

He visited his pal, the long-time Yankee catcher and manager.

“Yogi, you still love movies?” Villante asked.

“Yeah, I love movies if I like ’em,” Berra said.

Eventually, Berra agreed. The camera focused on Berra. Off camera, Villante asked him questions about the movies. “See, Yogi isn’t funny telling jokes,” Villante explained. “He’s funny in response to things.”

They opened up with the 1980s thriller Fatal Attraction. Berra called actress Glenn Close Glen Cove.

“Yogi, did you get scared?” Villante asked.

“Nah, nah, nah,” Berra said. “I only got scared at the scary parts.”

Stroh’s Beer turned it into a national spot campaign. Yogi at the Movies aired all over the country for several years.

In 2015 when Berra died, the world mourned the passing of one of its stars. Villante, as happens more often every year, mourned the loss of a friend.

He took to his office computer and sent out his memories in Me and Alphonse.

Villante’s field of dreams has narrowed to his office, his baseball diamond a computer screen.

His musings no longer become big national ad campaigns like Yogi at the Movies or Baseball Fever: Catch It. But through them the legends of America’s game live on.

And everyone is a kid again.

Tom Villante ’49 remembers the man who shattered baseball’s color barrier, Jackie Robinson.