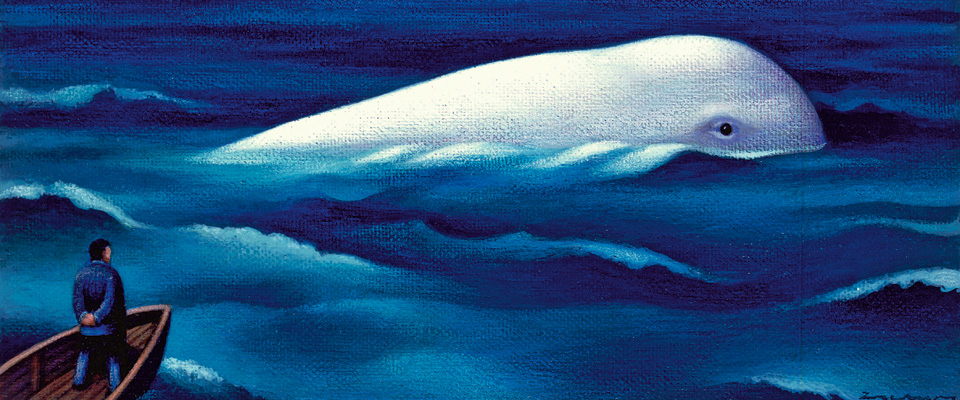

Riding Melville’s Whale

By Geoff Gehman ’80

There’s something about Moby-Dick that makes normally sane writers hunt its meaning almost as insanely as Captain Ahab hunts the white whale that swallowed his leg. They write about marathon readings of Herman Melville’s ultra-marathon novel. They write about the notes Melville made in the margins of whaling books he read to research his own book. They rewrite his epic, chapter by chapter and, sometimes, word for word.

Three literature professors with Lafayette allegiances recently tossed their harpoons into the ring and took Melville’s whale for a Nantucket sleigh ride. Melville is a mad genius, way ahead of and way behind his time, in the novel The Passages of H.M. (Doubleday, 2010) by Jay Parini ’70, a poet and a prominent biographer of adventurous writers. Christopher Phillips, an assistant professor of English and an authority on Melville’s poems and Pacific novels, depicts Melville as a radical political storyteller in his book The Course of Epic in American Culture, Settlement to Reconstruction, which Johns Hopkins University Press plans to publish in 2012. In Of Whales: in Print, in Paint, in Sea, in Stars, in Coin, in House, in Margins (Salt Publishing, 2010), a collection of poems and poetic prose pieces, Anthony Caleshu ’92 casts himself as a Melvillian sailor of the tides — and tidal waves — of fear, faith, and fatherhood.

All three men are fascinated by the way Melville turns literature into a cosmic sail. All three know that Moby-Dick is less about a vengeful quest than about ordering the laws of the universe. As Caleshu writes at the end of Of Whales, “We remind ourselves that it is just a book: even if it tells the stories of our lives.”

THE INVENTIVE INTELLECTUAL

Jay Parini has written books about the lives of five fabled writers. He’s authored biographies of John Steinbeck, Robert Frost, and William Faulkner and novels about Leo Tolstoy (The Last Station, made into a film starring Christopher Plummer) and Walter Benjamin (Benjamin’s Crossing, being made into a film starring Stanley Tucci). In The Passages of H.M., he freely mixes fact and fiction to make Melville more of a person and less of a phantom.

“Melville is the X factor in American literature,” says Parini, a professor of English and creative writing at Middlebury College and the literary executor for another fabled writer, Gore Vidal. “No one really knows anything about him. He left few letters, and the ones he left are models of self-disguise. I almost didn’t have a vivid sense of his hard reality as a person; I didn’t think he was somebody I understood. So I dug back into all of his fiction and all of his poetry and I asked: Okay, what kind of person could have created Moby-Dick or Billy Budd? I was working backwards, inventing the sources of his fiction in a way, giving him flesh and blood.”

| Everything I Know I Owe to Moby-Dick By Anthony CaleshuThere’s the obvious: to forego vengeance, the value of manly camaraderie, you. But there was also the time I was solo in the South Pacific, adrift for days. Without witnesses, I’ve always maintained Without sponsorship, I was fortunate to have protection with polarization — That self-inflicted mission was never going to be easy. with the help of a kind woman at the resort, Reprinted with permission. |

The Melville in The Passages of H.M. is a domestic Ahab. A mutinous sailor. A lover of a cannibal woman. An employee in an Oahu bowling alley. A wildly ambitious, desperately unsuccessful novelist. An unhappy customs officer. A fairly happy poet. An abusive husband. A tragic father. A jealous romantic. A brilliant philosopher, out of time and tune.

Parini scatters shards of himself through the novel. He colors Melville’s trips around the world with details from his own visits to London, the Scottish Lowlands, and Red Sea caves. He places in Melville’s mind his own thoughts about writing poetry (“each poem was a discreet universe of feeling and thought”) and novels (“one man’s plot is another man’s bad luck”). He parodies rambling, obsessive Melville biographers by compiling laundry lists of exotic plants, ancient ships, and other plot derailers.

Passages has many flights of fancy. The flightiest and fanciest involve writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, Melville’s friend, rival, and Moby-Dick dedicatee. Parini built the character of Melville’s wife Lizzie, who was far more mysterious than her husband, from a single description — “wry and smart” — uttered by Hawthorne’s wife after a tea. He invented a letter from Hawthorne to Melville praising Moby-Dick (“like every great and noble work of the imagination, it changes how we think, act, dream”) to illustrate Melville’s desperate need for Hawthorne’s respect and affection. He embellished this desperate need by conjuring a scene where Hawthorne rebuffs a romantic advance from Melville, whose fiction is animated by passion and love between males.

Parini admits Melville would have been severely displeased by this homoerotic fantasy. “He might have plunged a quill into my artery,” Parini says with a chuckle. “Even if I got it right, he wouldn’t be happy with me. I think he’d be happy that I took him seriously as a writer and put him implicitly on a par with Homer and The Odyssey. I think no writer can complain about that. I mean, every writer wants to be overestimated in his lifetime – it’s like the dream. Melville was underestimated in his lifetime, so, at least, posthumously, I’m giving him his due and then some.”

Parini began giving his Melville his due at Lafayette, where he studied epics of all stripes with such scholarly orators as W. Edward Brown and James Lusardi ’55. As a graduate student, he was mentored in Melvillian matters by the distinguished writer-teacher Robert Penn Warren, an early champion of Melville as a modernist poet. He’s raising Melville’s personal stock by writing a screenplay of The Passages of H.M. for actor-producer Paul Giamatti, who played a cranky Tolstoy disciple in the film version of The Last Station.

“Melville was underestimated in his lifetime so I’m giving him his due and then some.” – Jay Parini ’70

Parini is especially pleased that Passages has compelled his former students to read Melville novels for the first time, or from cover to cover for the first time. “This is the great success of my book — that it actually lures people back to Melville himself,” he says. “I’m nothing if not an advocate for the man. I grew to love him by inventing him.”

THE CULTURAL CARTOGRAPHER

Chris Phillips vividly remembers the moment when Moby-Dick first hooked him, line-and-sinker. He was a college sophomore enrolled in a survey of American literature, majoring in political science because it was “useful” and English because it was “fun.” He was reading a chapter in Moby-Dick on whaling law when Melville suddenly invited him, the reader, to join a debate over owned vs. ownable creatures: whales, factory workers, Mexicans. Phillips marveled at how Melville abruptly changed course, stepping into his story and becoming a political anthropologist.

That moment helped shift Phillips’ academic compass, pointing him to write an honors thesis on Melville and the law. A decade later, he is a cultural cartographer who charts literature’s many roles in the world, exploring everything from how Americans read old hymns to how Melville mapped his Pacific novels. In his new book, The Course of Epic in American Culture, he builds a scrupulous, nearly legalistic case for Melville’s creating a bravely novel form of novel, the encyclopedic epic.

According to Phillips, Melville in Moby-Dick greatly expanded the traditional Homeric epic with vast visual descriptions of the lives of whales and whalers. He collapsed the aesthetics of class, elevating primitive artifacts — scrimshaw, war clubs — to the status of noble antiquities. A daring, demanding storyteller, he plugged parallel and overlapping narratives into a switchboard of world views. Exhibit A in Moby-Dick is a chapter with nine perspectives on a gold coin Ahab nails to the mast of the Pequod and promises to the first man who “raises” the white whale, the captain’s infernal enemy.

Of course, many readers have been tempted to impale Melville’s novel after slogging through the doubloon episode. “There’s no user manual for Moby-Dick,” says Phillips with a laugh. “The first 100 pages are ridiculously slow. But the book is extremely profound and provocative. It’s also extremely funny; Melville even makes penis jokes. Too many readers expect it to be serious and good for them in the way that vegetables and exercise are good for them. They miss Melville’s point that literature is an experience like anything else. It’s an experience like whaling or sailing around the world. Look, if you’re looking for the whale in this book — the whale is the book.”

Phillips encourages students to catch their own Moby-Dick in his course Literature of the Sea, which he’ll teach again this fall, this time with new material on the Indian Ocean and the slave trade. He essentially urges them to ride Melville’s whale, bareback. “I tell them it’s not only the Great American Novel, it’s the Great American Rorschach test. So make a case for your angle. You don’t have to have dinner with Ahab, but, if you did, what would you talk about?”

Phillips would have plenty to talk about at Melville’s dinner table. After all, Phillips is the same age, 32, Melville was when he wrote Moby-Dick. The doting father of two young boys, Phillips is intrigued by how Melville, a bad father, still had the sensitivity to write the wrenching moment when Ahab sees his missing family in an officer’s eyes.

Phillips’ four-year-old shares his fascination with whales. Father and son also share a nervousness around the ocean; Phillips’ one whale-watching trip made him “terribly” seasick. Their safe harbor is the aquarium.

THE POETIC SHAPE-CHANGER

Anthony Caleshu grew up watching whales off the coast of his native Massachusetts. He didn’t consider writing about whales, however, until he was living on the other side of the Atlantic. He was a doctoral student in Ireland, working in a Galway bookstore, when he happened to pick up a copy of Moby-Dick. He’d read the novel in high school with little impact, but this time he was enchanted by Melville’s wildly inventive language and outrageous rhetoric. He found himself rereading paragraphs, savoring their “ecstatic lyricism,” gladly distracting himself from working on his dissertation.

Melville gradually became Caleshu’s captain. Moby-Dick made Caleshu think about being American in a foreign land. Living in England, with his wife expecting their first child, Caleshu began embracing Melville’s stories about fathers and sons. All these forces spurred him to write Of Whales as a triple threat: a family album of humanity, a mini-epic of performance poetry, a cosmic circus of shape-changing.

Caleshu riffs off everything from a sailor’s chapel to a whale bone outside Hawthorne’s house. He applies for a grant to write the Great American Novel, promising to become a failed farmer like Melville. He morphs into a sea captain who offers a son five reasons why whaling is so seductive. And he appears in several poems as a father who, by comforting a child lost in a sea of sickness late at night, finds a kind of equilibrium, a sort of psychological land. He ends “Wonderfullest Thing” with the acute observation: “In bed alone,/I am shoreless when you go quiet/and as indefinite as god.”

Caleshu does in Of Whales what Melville did in Moby-Dick. He plays the skald, creating original stories from borrowed sources, professional and personal. He references Melville’s references, including J.N. Reynolds’ book Mocha-Dick: or, the White Whale of the Pacific. He conveys his feelings of holding his son Parker to his chest to soften the boy’s miserable ear infections. He merges the loneliness of a sailor at sea with the brief, strange distance he felt when he saw his son and wife in England after a month-long whaling research trip in the United States. “It hit me how entering a fictional space had removed me from the real world for some time.”

Of Whales has spun off an extended literary family. A poet Caleshu admires but had never met told him she “didn’t know contemporary poetry could be so fun.” A history professor saluted his attempt to “strike up a friendship with an author and his work.” Caleshu continues this mission in his new collection, The Victor Poems, a rough search for a long-lost friend. The Victor Poems and Of Whales, in turn, honor his friendship with his Lafayette poetry mentor, Lee Upton, professor of English and writer-in-residence. “I can’t overstate just how much of an influence Lee has had on my reading and writing over the years,” says Caleshu, an associate professor of English and creative writing at the University of Plymouth and editor of the literary journal Short FICTION.

Like Phillips and Parini, Caleshu would like to grill Melville about his many mysteries. Caleshu would like to ask Melville why he was such a pompous philosopher with the practical Hawthorne, why Melville ranted about “ontological heroics” when all Hawthorne wanted was for Melville to pick up his parcel at the railroad depot. Caleshu would like to ask Melville how he wrote 150,000 words of Moby-Dick in a white-hot 13 months and why he never left behind a draft of his masterpiece.

Like Parini and Phillips, Caleshu is grooming another generation of Melvillians. He’s happy that he’s inspired the five-year-old Parker, whose ear tortures he soothed, to write his very own Moby-Dick and his very own The Imagination of Whales.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Anthony Caleshu ’92 is the author of two books of poetry and a novella. His poems and stories have appeared in journals and newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic, including Times Literary Supplement, Poetry Review, Poetry Ireland Review, The Dublin Review, American Literary Review, and Agni Online.

Anthony Caleshu ’92 is the author of two books of poetry and a novella. His poems and stories have appeared in journals and newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic, including Times Literary Supplement, Poetry Review, Poetry Ireland Review, The Dublin Review, American Literary Review, and Agni Online. Jay Parini ’70, D.E. Axinn Professor of English and Creative Writing at Middlebury College, is the author of seven novels, five volumes of poetry, and nine major works of non-fiction and criticism. The College awarded him an honorary Doctor of Letters degree in 1996.

Jay Parini ’70, D.E. Axinn Professor of English and Creative Writing at Middlebury College, is the author of seven novels, five volumes of poetry, and nine major works of non-fiction and criticism. The College awarded him an honorary Doctor of Letters degree in 1996. Christopher Phillips joined the faculty in 2007 with a doctorate from Stanford University. His teaching and research interests include American and transatlantic literatures of the 18th and 19th centuries, literary history, the history of the book and of reading, religion and literature, literary history, and the literature of the sea.

Christopher Phillips joined the faculty in 2007 with a doctorate from Stanford University. His teaching and research interests include American and transatlantic literatures of the 18th and 19th centuries, literary history, the history of the book and of reading, religion and literature, literary history, and the literature of the sea.