Within reach

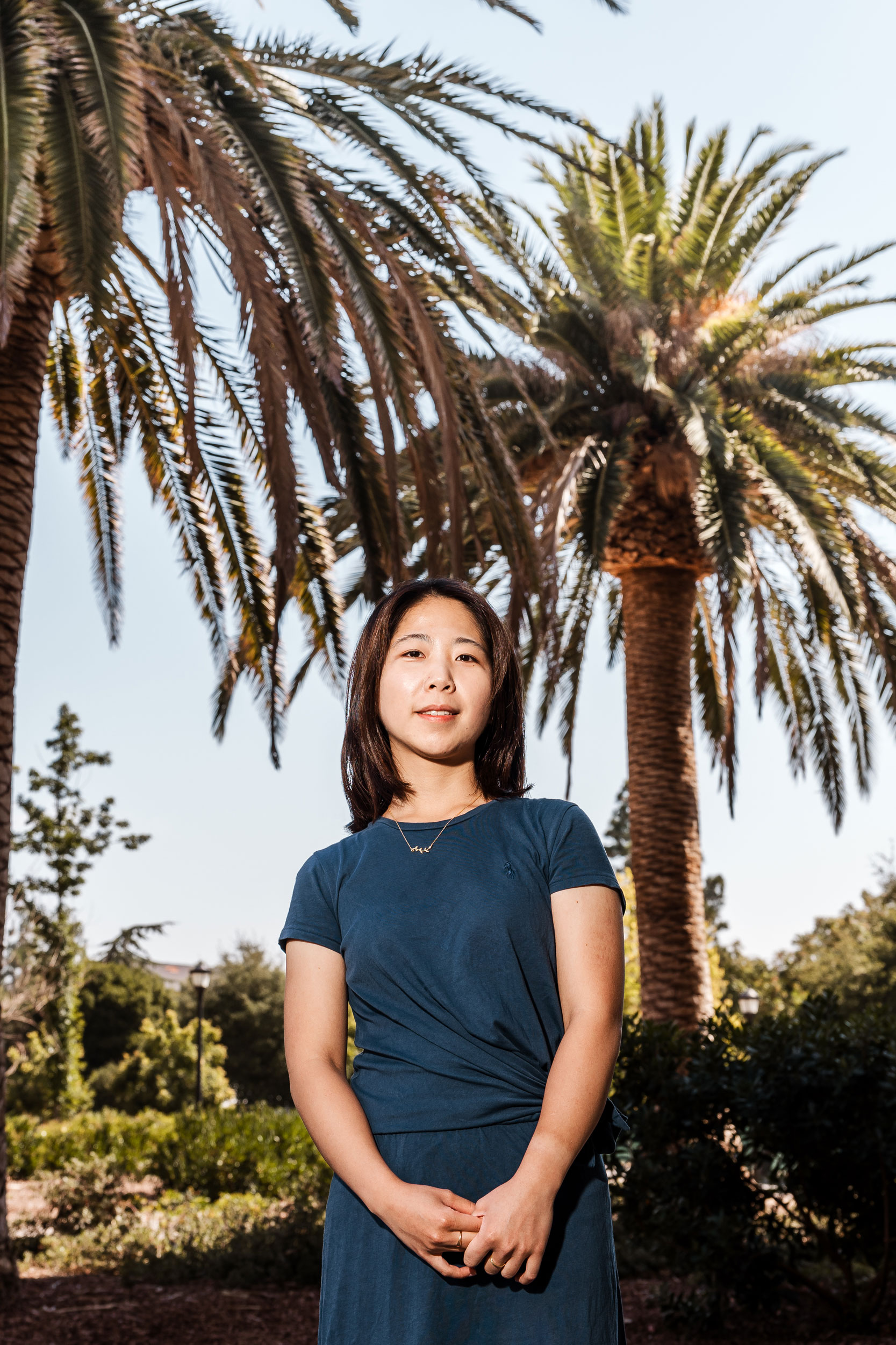

Manaka Gomi ’23 is improving the instrument, and the sounds, for pianists like herself.

Manaka Gomi ’23

Photograph by Carolyn Fong

Pianist-mechanical engineer Manaka Gomi ’23 is designing a keyboard that’s inclusive of musicians with smaller hands.

Following in the keyboard alteration tradition of Chopin and Liszt, Gomi (mechanical engineering and music, and now a Ph.D. student in mechanical engineering at Stanford University) is allowing pianists with smaller handspans to more comfortably reach a tenth, an interval that’s often demanded in Romantic repertoire but out of reach. “The keyboard is standard across the world. If you have smaller hands, it’s harder to play,” she says.

Her Lafayette piano instructor, Prof. Holly Roadfeldt, knows all about technical limitations when approaching certain repertoire. With smaller hands too, she’s been a supportive and sympathetic collaborator as Gomi continues to refine her prototype.

“In almost all works from the standard repertoire, a handspan of a ninth is required, but it is common for composers, like Rachmaninoff and Brahms, to include an interval of a tenth. Manaka and I can only reach that ninth,” she explains. “So you have to manipulate certain passages.”

Gomi has begun her endeavor by designing and building a hammer mechanism set in a block of aluminum, instead of the usual wood, and choosing a bronze guitar string, instead of traditional steel piano wire, to amplify sound uniquely.

The project “really allows her to use what she knows already, as an engineer and a musician, and to learn new things,” says Jenn Rossmann, professor of mechanical engineering and Gomi’s academic adviser.

Rossmann notes another benefit of her design: “A grand piano is not something you can put in the back of your car and take to your next gig. So portability was one design objective, along with inclusion.”

Kirk O’Riordan, composer, performer, and associate professor of music and director of bands, has been a Gomi fan since she enrolled in three of his music courses.

“Her project is fascinating, dealing with different ways of shaping the keyboard as an interface device to create a variety of different sounds,” he says. “As a composer, that automatically has a great deal of appeal to me.”

He describes the project as the epitome of Lafayette’s tradition of combining engineering and the humanities. “I don’t know how it gets any better, frankly,” O’Riordan says. “You’re using engineering to facilitate the creation of art.”