Illustrations by Fernando Cobelo

Inside the Gov Lab

While college students influence the U.S. political landscape, a group of students at Lafayette examines what might motivate Gen Z to vote.

Liliana Roginski ’25 wasn’t old enough to vote the last time the nation decided its president, but in November, she joined millions of her peers among the country’s newest and youngest generation of voters.

Leading up to her first Election Day, Roginski was invested in the behavior of other college-age voters. While working in the Gov Lab of Andrew Clarke, assistant professor of government and law, she and other students spent months digging into a deep and timely question: How do college students in swing states, one of the most influential demographics in electoral politics, get motivated to vote?

As the Lafayette community approached the 2024 presidential election, Roginski and her fellow Gov Lab student managers were running an experiment across campus to determine exactly how to mobilize college students. This work, just the latest in a series of nonpartisan, politically focused research projects conducted by Clarke and his lab, left the group with some interesting observations.

An idea hatches from the pandemic

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic had started to derail in-person summer professional development opportunities, including for Julia Cassidy ’22.

Cassidy, then a sophomore, had just written a term paper for Clarke’s Political Analysis class, focusing on reducing the gender gap in political candidacy. After reading it, Clarke was impressed by its potential applications.

“I said ‘Hey, do you want to actually do something out in the world with this?’” Clarke says. “And that became Gov Lab.”

With support from Prof. Helena Silverstein, department chair of government and law, and Chelsea Morrese, executive director of the Landis Center for Community Engagement, who secured financial and logistical backing for the project, Clarke and Cassidy were able to gather a group of student volunteers to work remotely, compiling a database of political activists and local party leaders in every county throughout the United States. “Every semester, we had more people doing research,” Cassidy says.

The team used their database of party leaders and activists from around the country to solicit advice for Lafayette students interested in public service, wondering if more advice would be offered to gender-specific groups. Ultimately, they found enthusiastic support for groups like the Lafayette Women in Law Society, especially from Republican women.

Eventually, Cassidy and Clarke were able to publish a research paper on their findings in the Journal of Women, Politics & Policy. The opportunity to be a published co-author as an undergrad is commendable, and especially outside of science fields. “You don’t write a paper for a class and feel like it’s going to escalate to this point,” Cassidy says. “But it’s pretty cool that I inspired something like that. Not a lot of people have that experience.”

“This research is about people my age, our impact, and what we can do,” says Emma Li ’27.

Gov Lab, as an organization, has always been student-led. Currently, four student “team leads” each manage a support staff of volunteers. As students graduate and new ones join, group projects within Gov Lab evolve. Each summer, the students identify a new topic in politics and spend the academic year researching it.

Although he is available for mentoring, Clarke emphasizes student leadership in his lab. “I take, quite seriously, giving the Gov Lab managers control over what the project will be, because they do so much work,” Clarke says. “To manage personnel, to do research designs, to do all this—I want them to be invested in the topic personally.”

From 2021 to 2023, the Gov Lab team initiated the Peer2Power Project, a study that focused on how peer networks impacted political action. The team, led by Deja Jackson ’23, built a mobile app to determine the efficacy of friend-based recruitment for political campaigns—in other words, could your social group influence you to get more involved in politics?

During last year’s Gov Lab study, students conducted a mass e-survey of leaders on education policy. This project resulted in more than 80,000 emails to public officials, school board members, state legislators, and others. In a randomized control trial, students asked those policymakers for their opinions on a variety of important topics, such as free eyeglass clinics in schools, programs to increase social belonging among middle schoolers, and the prospect of AI-informed tutoring services. The experiment found that public officials consider scientific evidence when planning educational policies.

Investment in Gov Lab, and in political research as a field, is a through line for these students. Today, Cassidy works as a legal assistant at a law firm in New Jersey as she applies to many of the top law schools in the country. A Gov Lab team lead from 2022 to 2024, Guilia Matteucci ’24, currently serves as a researcher at the Library of Congress, after being named a 2023 Newman Civic Fellow. Other members of the group have gone on to positions at the Young Democrats of America, and Peace Corps, and enrolled in prestigious postgraduate schools.

“Gov Lab expands throughout the years, and it grows bigger and bigger,” Roginski says. “It’s getting more recognition, and it’s a great opportunity for students to create research.”

Finding meaning in an election year

Roginski, alongside fellow 2024 managers Samantha Natividad ’25, Kate SantaMaria ’27, and Emma Li ’27, came together with the rest of the team during summer 2024 to determine their research topic. As for many across the country, the presidential election was on their minds.

“This is a really precious time,” Li says of the team’s decision to focus on elections. “We won’t be in college during another presidential election. A huge part of elections is getting people involved, so this research is about people my age, our impact, and what we can do.”

Ultimately, the group decided to first measure political engagement on college campuses, particularly in swing states like Pennsylvania, Arizona, and Michigan.

“Swing states have the capability to determine the course of the election,” Roginski says. “We looked into what college campuses [in those states] have done in the past and what they’re doing now with that sort of elevated position.”

The group gathered data not only on publicly available variables, like voter turnout and voter registration, but also measures of political engagement that are harder to quantify, such as protests, turnout in student government elections, placement of alumni in government careers, and more. Schools surveyed ranged from large institutions, like University of Michigan at Ann Arbor and University of Georgia, to small community colleges and other Patriot League schools.

Alongside Dylan Groves and Stephanie Chan, assistant professors of government and law who joined Gov Lab as co-directors this year, the team analyzed the data using statistical software to discern which college campus communities stood out as particularly engaged. Once that data was collected, the Gov Lab team set out to build an experiment on campus.

“It’s a pilot study of how to mobilize,” Clarke says. “We ultimately decided that we really wanted Lafayette to be engaged this year, so let’s figure out how to do it here first.”

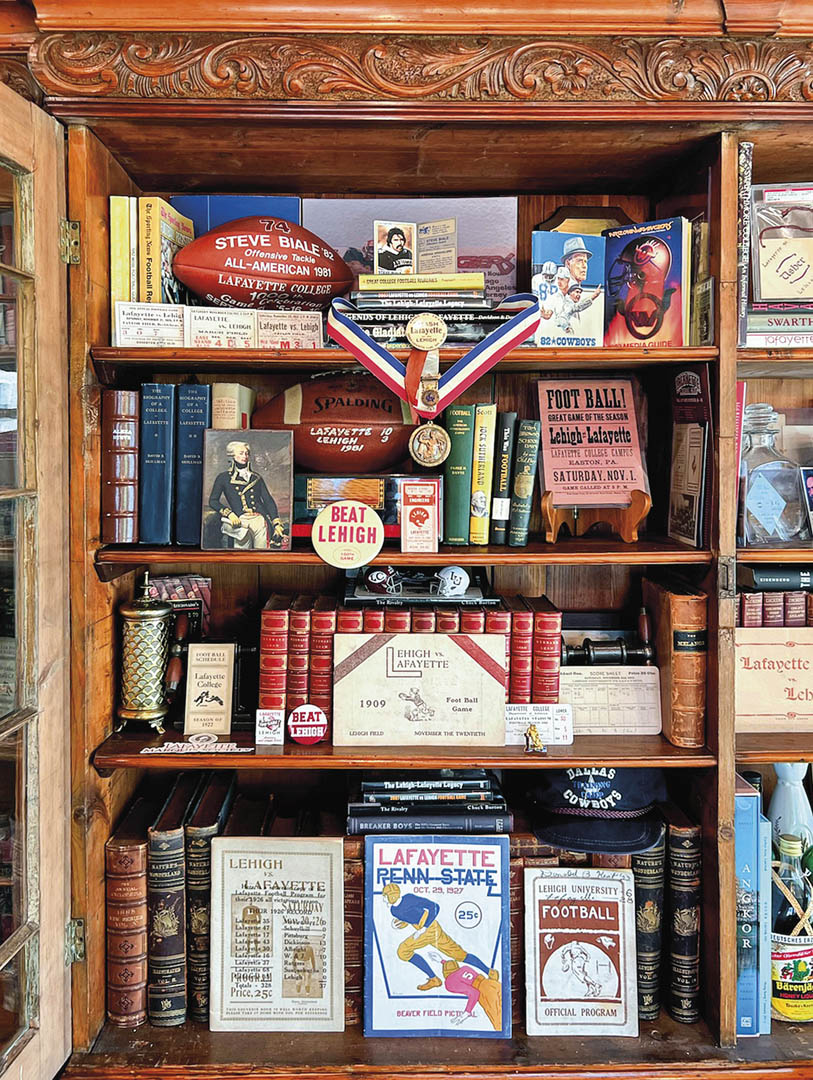

They settled on testing an unconventional theory: Could a sense of competition impact voting among students? And, in Lafayette’s community, it was easy to identify what fuels the most competitive spirit—the rivalry with nearby Lehigh University.

To carry out the experiment, the Gov Lab team distributed messaging across Lafayette’s campus leading up to the election, asking students to get engaged in order to “Beat Lehigh” on registration and turnout numbers. A control group was given the same information—with no rivalry messaging.

The student managers wanted to build their project around competition because of its generalizability.

“Many other colleges have a rival school,” SantaMaria says. “Even if they don’t, they have access to competition, because nearly every college has a sports team of some sort. So we’re taking this competition that already exists and seeing if we can put politics into it in a way where political engagement is increased.”

In the weeks leading up to the presidential election, Gov Lab researchers utilized a variety of in-person and digital outreach methods, carefully designed to be nonpartisan, to encourage their peers to get involved in the political process.

On Election Day, college students around the country showed up en masse. There was such a high turnout on campuses in the Lehigh Valley that Northampton County sent extra voting machines to both Lafayette College and Lehigh University to accommodate the crowds. Throughout the day, the Gov Lab team observed, and stood in, the long lines wrapping around Kirby Sports Center, Lafayette’s polling place. They noticed many students from their Gov Lab contact list also waiting—at times, at least three hours—to vote. Over in Bethlehem, Pa., it was reported that voters, many of them Lehigh students, stood in line for up to seven hours.

Student voters are key to unlocking decisions

College students have a significant role to play in the future of electoral politics. According to the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University, 8.3 million young people have aged into the electorate since the 2022 midterm elections. And the power is only growing: By the 2028 election, the voting bloc of millennials and Gen Z will account for the majority of the electorate.

“I think that as college students, we’re in this really interesting transition from being a kid to being an adult,” SantaMaria says. “For a lot of students, when you walk onto campus, you will be voting in your first election. I think it presents the perfect opportunity to learn about politics, and college campuses can be such a hub of accurate, unbiased information for students to develop their own political identities.”

Because college students are allowed to change their voter registration to their campus address, students going to college in a swing state like Pennsylvania may feel that their vote can make more of a difference.

Li, who is originally from St. Louis, Mo., changed her registration to her Easton, Pa., address when she matriculated last year. “I wanted to have my vote actually matter,” she says. “Not a lot of people switched my first year, but a lot of my friends are switching this year, because it’s more talked about and more contentious than a typical election cycle.”

“For a lot of students on campus, it’s their first election,” says Kate SantaMaria ’27. “It presents the perfect opportunity to learn about politics.”

According to campus organization Lafayette Votes, 82.9% of Lafayette students voted in the 2020 presidential election. During both the 2020 and 2024 presidential races, Pennsylvania’s results were a pivotal deciding factor in the outcome. In the week leading up to the election, the presidential candidates from both the Democratic and Republican parties made campaign stops in the Lehigh Valley, including one to a college campus in Allentown, Pa., the day before the election.

No matter how they get engaged, student voters can have a lasting impact on the American political landscape. “Young people can definitely make a difference,” says SantaMaria, who is 19 years old, “and we can have an impact on a greater scale.” And regardless of the results of the election, or their research projects, Gov Lab has made a lasting impression on the Lafayette students involved with it.

“I’m grateful for this opportunity,” SantaMaria adds. “One of the reasons I chose to go to Lafayette was because I wanted to be able to have research opportunities as an undergraduate, and this has completely exceeded my expectations.”

Although the election is now over, Gov Lab’s student managers and volunteers will continue to work on this project into winter and spring. In the coming months, the group will continue to encourage and analyze other important forms of student engagement such as attending campus political events and writing op-eds in the student newspaper. Once the research is complete, this year’s team leads will work to write an article for a peer-reviewed academic journal on their findings.

“I’m aiming to apply to law school next fall,” Roginski says. “So being able to say that I’m a contributing author on a working research paper is beyond my imagination. It’s amazing.”

Looking back on her experience and the impact her work as the first Gov Lab manager made, Cassidy encourages current and future Lafayette students to take risks.

“If there’s some sort of project you’ve been thinking about and think there’s no outlet for it, look into it and see where it can take you,” she says. “You never know. You could publish a paper from it.”