by Chris Quirk

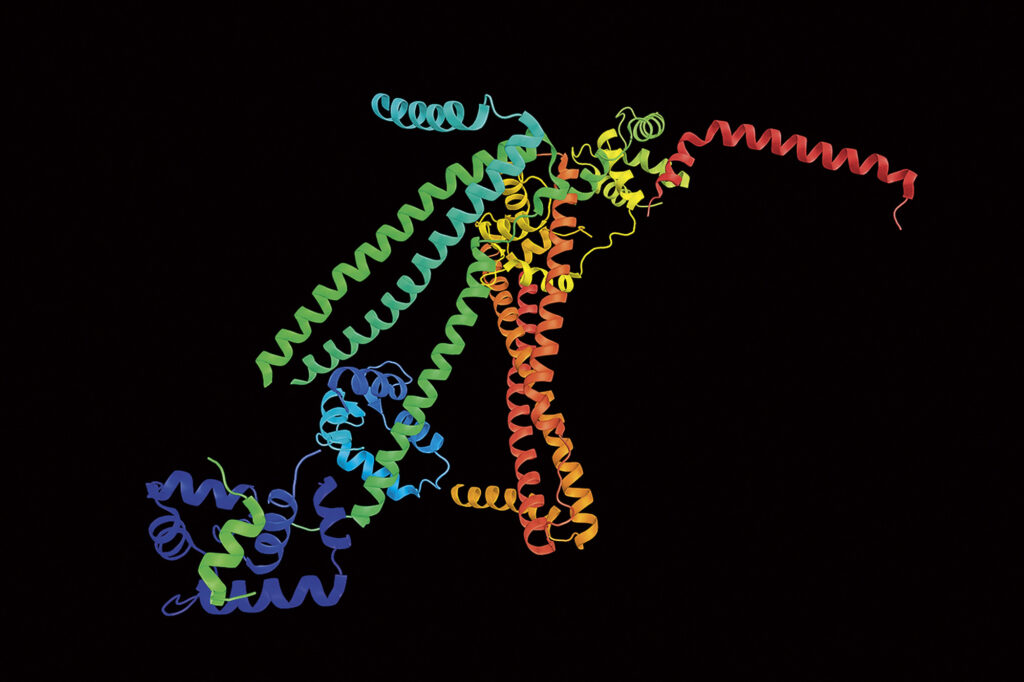

Spencer Keene ’14 is examining specific troponin biomarkers, a protein (visualized above) that’s found in heart muscle cells, can signal heart injury, and may help predict cardiovascular disease risk. The study was published by JACC Journals in April.

Photograph by Shutterstock

As researchers find new and more efficient ways to measure hard-to-trace biomarkers, they are providing new possibilities for diagnosis and care to clinicians. Spencer Keene ’14 (biology), a research associate in the Department of Public Health and Primary Care at University of Cambridge in England, has been investigating the use of cardiac troponin as a biomarker to improve risk assessments for cardiovascular disease.

Cardiac troponin is a protein released into the bloodstream when there is damage to the heart. It has typically been used to acutely diagnose heart attacks in patients, even in cases where a person may be unaware they have had one. “Sometimes a mild heart attack feels like an arrhythmia, or there may be temporary pain,” Keene says. “But you obviously want to know about it so you can take the proper steps clinically.”

With new testing methods, physicians can now detect cardiac troponin levels in minuscule amounts, and Keene is researching cardiac troponin as a tool for preventing the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease. “The presence of cardiac troponin in the bloodstream could indicate an underlying heart issue in a patient with otherwise normal risk,” Keene says. “The higher the levels, the more damage you expect.” And, like Alzheimer’s disease, early detection of unusually high levels of the biomarker could lead to more timely interventions.

Keene and his colleagues looked at data from more than a dozen heart health studies that included 60,000- plus participants to conduct a meta-analysis. The team waded through the vast amounts of raw data on individuals included in the studies.

They then went through the laborious process of harmonizing the data from the various studies to ensure they were analyzing apples-to-apples data from the original studies, and generated their results. “A meta-analysis gave us improved statistical power, and gave us greater precision in our estimates compared to getting results out of a single study,” Keene says.

The results showed that by testing for cardiac troponin, about one in 400 cardiovascular events could be prevented. While this is a low proportion, when applied to a national population, for instance, the absolute number is high, and the screening could potentially save many lives and reduce health care costs as well.

Keene envisions that eventually cardiac troponin could be added to the panel of tests used for predicting an individual’s 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease. “If you are low risk in the existing risk prediction model, adding a cardiac troponin test probably won’t influence what a doctor would do in terms of, for instance, prescribing treatment with statins,” Keene says. “But if you have intermediate risk, then if you measure high for cardiac troponin, the doctor may move you into a high-risk group and recommend statins in addition to lifestyle changes.”