Living history

The causes and qualities of the Marquis de Lafayette continue to draw scholarly and public interest. They also reflect the ideals of our College.

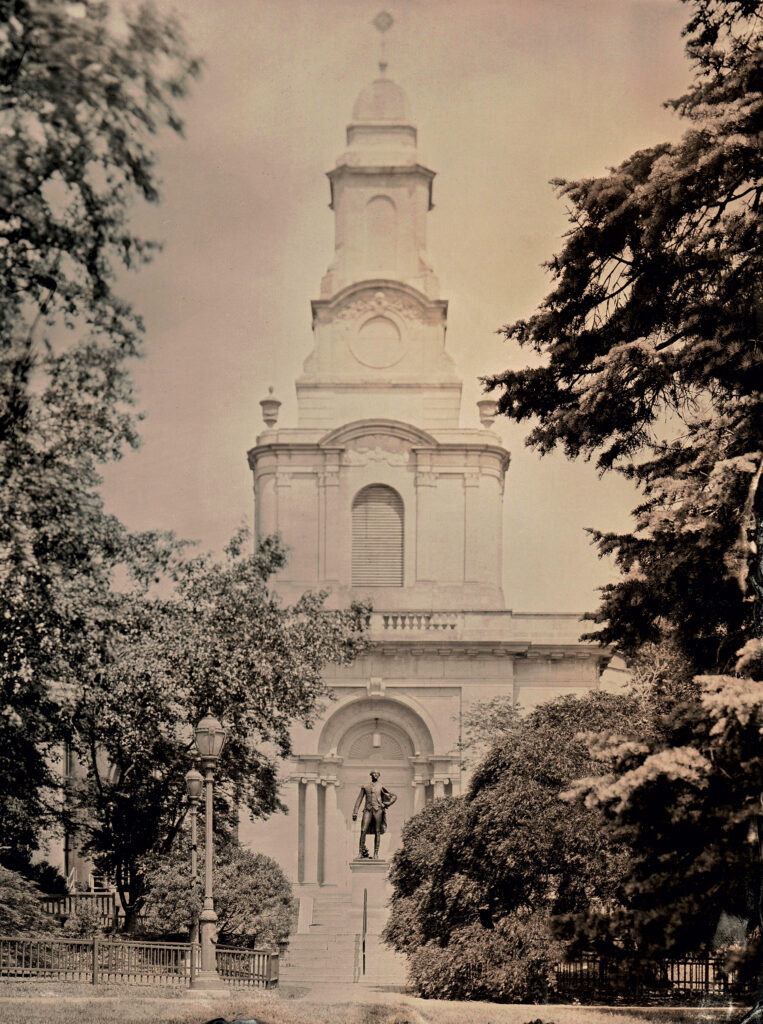

Lafayette’s statue, seen here in 2025, is framed by the arched entrance to Colton Chapel.

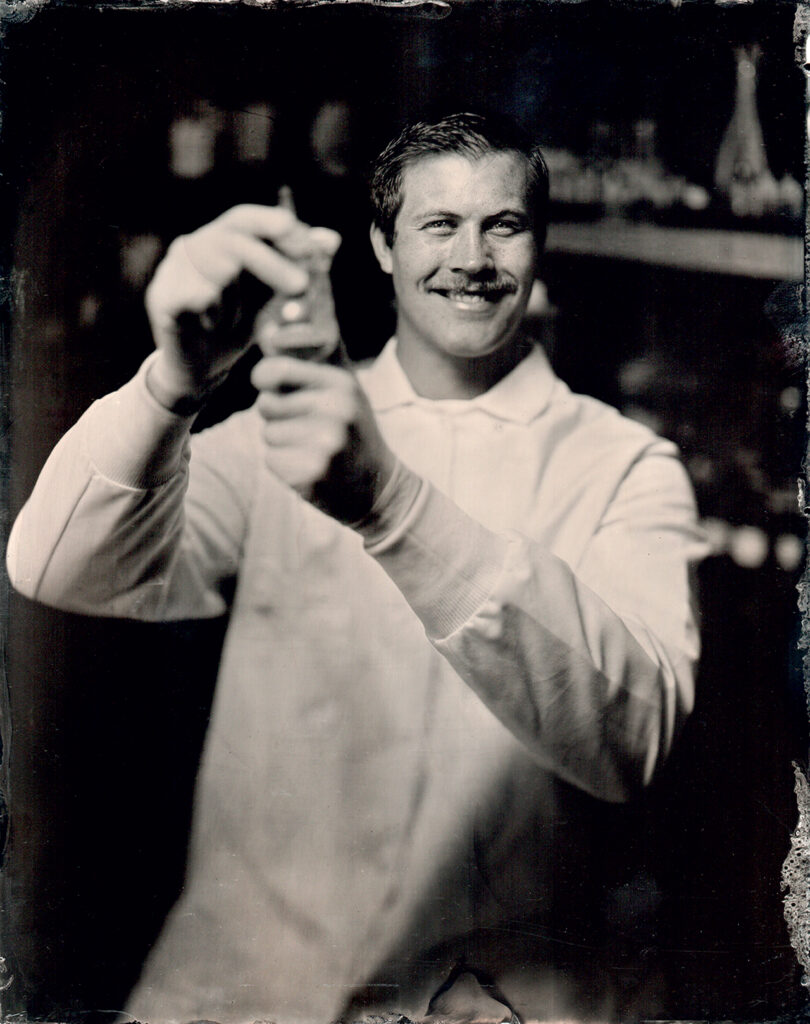

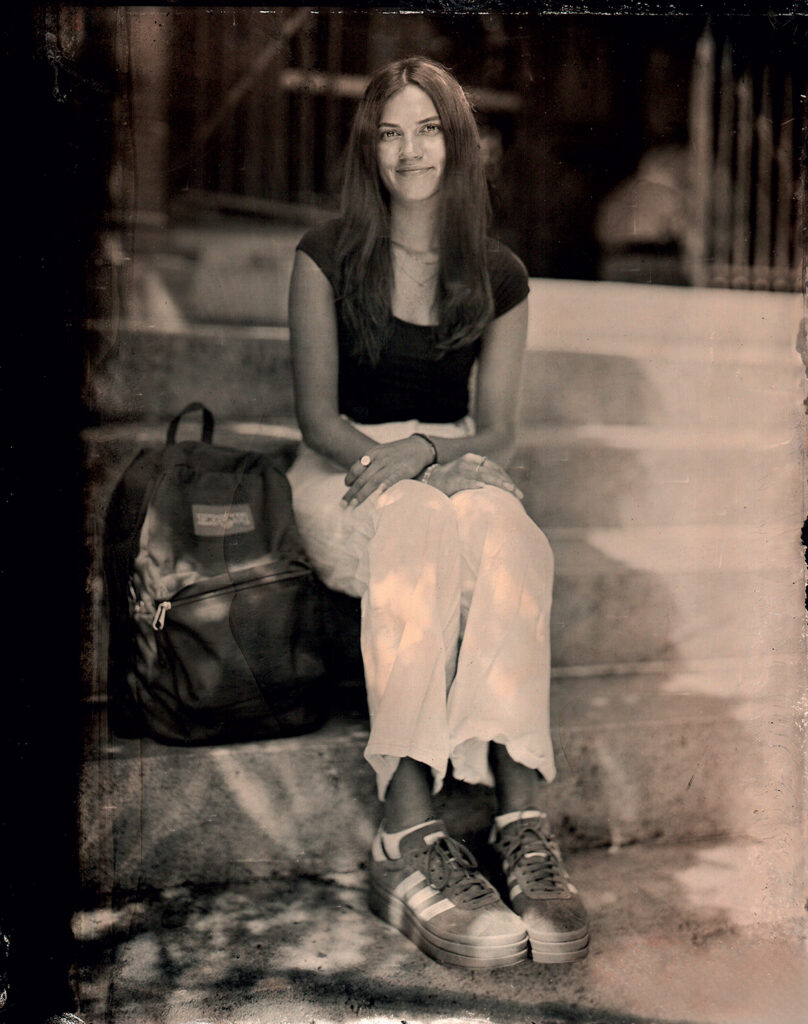

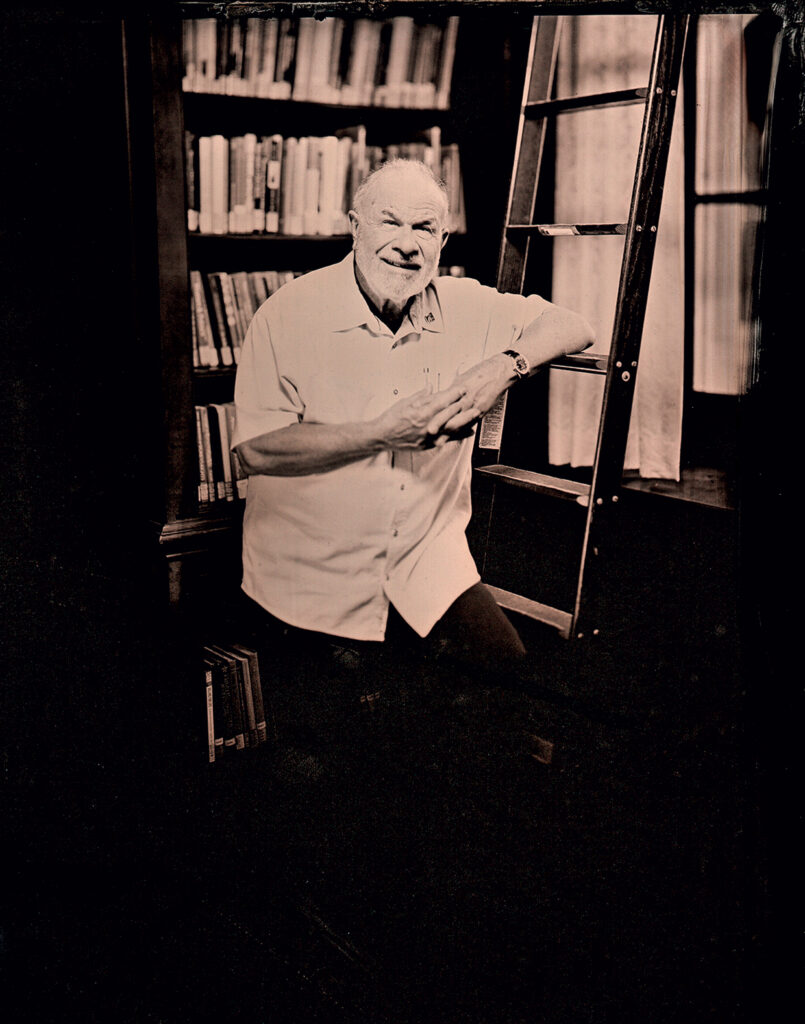

Photography by rick smith

What was it about the Marquis de Lafayette that made him a college’s namesake—and a character in a hit Broadway musical? A decade or so ago, Daveed Diggs was aware that Lafayette was a key French figure in the American Revolution. “That was about it,” he says today.

Then Diggs earned the role of Lafayette, and of Thomas Jefferson, in the original cast of Hamilton. In “Guns and Ships,” rapping at a reported 6.3 words per second—hardly the fastest rapping of his career, he notes—Diggs introduced the Marquis de Lafayette as a secret weapon in the Revolutionary cause: “He’s constantly confusin’, confoundin’ the British henchmen./Ev’ryone give it up for America’s favorite fighting Frenchman/Lafayette!”

Lafayette! As its Bicentennial approaches, why should the College identify with or even care about the fighting Frenchman? The United States has a long history of naming colleges for donors or for “Great Americans,” says Charles Dorn, a historian of education at Bowdoin College in Maine, which awarded an honorary degree to the Marquis de Lafayette. “It’s pretty unusual for an institution to be named after an admired foreigner,” he adds.

“What we tend to forget today is that the Marquis de Lafayette was for some time considered almost equal to Washington as ‘the’ hero of the American Revolution. At the time Lafayette College was founded, in 1826, many Americans were still foreign-born, the country was multilingual, and the kind of national fervor we’re used to today did not exist. Americans simply had little problem crediting a foreigner with the Revolution’s success.”

Diggs, the rapping Marquis de Lafayette, who was tutored along with the rest of the cast by Alexander Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow, certainly sees him as credit-worthy. Lafayette embodied the idea that “passions are worth pursuing and the things that seem important to you, that seem right for you, are worth fighting for,” he says. Then there was his eagerness to learn about the world, along with his desire to apply his learning to service—in particular, to the Revolutionary War, where a young foreign-born aristocrat had to earn his standing.

“And by all accounts, he was kind. People seemed to like the guy. That’s important to me.” Were he around at the time, Diggs says he definitely would have turned out for Lafayette’s 1824-25 triumphant return to America, which became known as the Farewell Tour. Lafayette visited each of the then-24 states, taking in more of America than any of the homegrown Founding Fathers. A stop in Philadelphia drew James Madison Porter, whose father had served with Lafayette at the Battle of Brandywine Creek. Porter and some 200 of his fellow Eastonians journeyed down the Delaware River for the welcome. Later, Porter called for a meeting in Easton’s Centre Square, where the attendees agreed to the founding of a college out of respect for “the talents, virtues, and signal service of General La Fayette in the great cause of Freedom.”

“The things that seem important to you, that seem right for you, are worth fighting for.”

Over the centuries, the admiration hasn’t diminished, a fact pointed out by Mike Duncan, author of Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution. Speaking at the College this past February, he said there are plenty of reasons for seeing the Marquis as a figure who belongs not just to history but to the present day as well. (Duncan was giving the Lafayette College Libraries’ annual John L. Hatfield ’67 Lecture, which brings a prominent author to campus for a public lecture and to meet with students.)

The values Lafayette represented are important. He modeled the sort of questions we should want to be asking of ourselves: Who do I want to be? How do I want to interact with the world?

As Duncan told the campus audience in Hugel Science Center, Lafayette “was born into a life of extraordinary privilege as a member of the nobility. The easiest thing for him to have done would have been absolutely nothing. But that was not the Marquis de Lafayette.”

According to Duncan, Lafayette harbored the sort of ambition that wasn’t aimless. “He would not just do anything to be famous. He wanted to do things for the greater good.” He was not a philosopher, or someone with a pronounced contemplative manner. But he absolutely was someone invested in a life of action—a life captured in his family motto, “Cur Non?” or “Why Not?”

“When he saw injustice,” as Duncan put it, he would summon the courage to “make the world a better place.”

Making the world a better place fed right into a program put on, five years ago, by The American Friends of Lafayette. It was titled “Character Matters: Perceptions of Lafayette and Lessons for our Time.” (According to the organization, there are approximately 80 cities, counties, townships, and towns in the U.S. that take their names from Lafayette or his longtime home, La Grange; there are countless streets, squares, statues, and parks, as well as a mountain and a lake named for him. And, of course, one college.)

One of the presenters, historian Lloyd Kramer of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, observed that Lafayette’s “decency and commitments to the ‘public good’ were valuable human traits that Americans recognized and appreciated during his lifetime—and traits that many Americans would like to see again in our contemporary political culture.”

Kramer added that “Lafayette always supported the development of constitutional institutions,” including free speech, a free press, and freedom of religion. He introduced a proposal for a Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen in the National Assembly during the first weeks of the French Revolution; he and his wife, Adrienne, were among the first Parisians to join the French Society of the Friends of Blacks, an antislavery organization; he supported free-thinking women who agitated for a more robust set of rights; and he promoted independence movements for countries around the world.

Lafayette’s ability to work across divides, in Kramer’s view, makes him exemplary for our own polarized time. “He became influential during the American Revolution as he mediated between the Americans and the French, and he continued to interpret or explain the cultural values and ideas of each national group throughout his later life.

“Equally important, the Revolutionary political conflicts in France pushed him toward a mediating ‘middle way’ within his own national culture. During the French Revolution, for example, Lafayette tried to protect the rights of people on both the political left and the political right. He faced the huge challenge of being a strong principled public leader who actually stood in the lonely middle of the political spectrum.”

One place to find the Marquis de Lafayette as a promoter of the public good is the College’s collection of historical materials. They include original letters from Lafayette to George Washington, many of which were written during the American Revolution.

In one letter, from 1783, he proposed a demonstration project: “Let us unite in purchasing a small estate where we may try the experiment to free the Negroes.” Washington delivered a gentle turndown. For his part, Lafayette would purchase two plantations in the French colony of Cayenne, now French Guiana, located on the northeastern coast of South America. Some 70 enslaved people came with the purchase; Lafayette began to pay them and to provide schooling. The aim was to prepare them for eventual emancipation.

That letter was one of the inspirations for an exhibition, A True Friend of the Cause: Lafayette and the Antislavery Movement. The exhibition opened in late 2016 at New York’s Grolier Club, the oldest bibliophile society in the country. It was co-curated by Diane Shaw, then-director of Special Collections and College Archives, and Olga Anna Duhl, Oliver Edwin Williams Professor of Languages. Duhl’s research focuses on late medieval and early Renaissance French literature, theater, rhetoric, translation, and textual criticism—and the Marquis de Lafayette.

Lafayette was always against slavery, according to Duhl. “He couldn’t process the idea that America, the land of liberty, would promote slavery. In his mind, this was a great paradox.” His South American plan inspired at least one admirer, the Scottish abolitionist and feminist Frances Wright, who joined Lafayette on his Farewell Tour in America. She later conceived a community in the Tennessee wilderness where enslaved persons would perform labor and earn their freedom; Lafayette was a trustee of the enterprise.

Lafayette’s efforts, like Wright’s, didn’t have much staying power. He lost all of his property during the French Revolution. But it was a striking example, for the times, of a desire to pave an uncharted path.

Duhl is now collaborating on another exhibition, Lafayette Between France and America: History and Legend, set for the National Archives of France from next April through Bastille Day, July 14. The exhibition will include about 114 pieces, some 50 of which will be from the College’s collection. Among them: memorabilia from the Farewell Tour; three paintings depicting Lafayette; and a model of the Hermione, the ship that carried him across the Atlantic for the third time. Plus, Lafayette’s letters to George Washington, among them the letter proposing the antislavery property.

The College’s co-directors of Special Collections and College Archives, Elaine Stomber ’89, P’17,’21 and Ana Ramirez Luhrs, have been working with Duhl on the Paris exhibition. Luhrs curated an earlier campus-based exhibition drawn exclusively from the College’s collections. All of the objects carried some sort of representation of Lafayette and testified to his “exalted” status, Luhrs says, as a returning hero: printed invitations, medallions, scarves, snuff boxes, plates, platters, a spyglass, a pipe.

Lafayette modeled the sort of questions we should want to be asking of ourselves: Who do I want to be? How do I want to interact with the world?

For the College, Luhrs is essentially the curator of all things Marquis de Lafayette. In the letters, he comes across as someone who was always inquisitive, always applying his virtues to a disordered world, and always interrogating conventional assumptions. Meaning he hewed to “Cur Non?”

Lafayette clearly clung to that family motto. A recent donation to Special Collections comes from the personal library of the Marquis: an eight-volume account of a fellow French aristocrat’s travels through the northern U.S.—a much earlier and geographically shortened version of Lafayette’s Farewell Tour. The title page of each volume has “Cur Non?” stamped on it.

The letters are likewise a big part of the portfolio for library colleague Nora Zimmerman, digital archivist and repository librarian at Lafayette. Zimmerman recently wrapped up the project of digitizing the letters to Washington. There’s Lafayette writing from Valley Forge in 1777, from Boston Harbor in 1780, from New York in 1784, from Paris in 1792, and much else across time and geography—nearly 150 letters in all.

“You can see him grow up and mature,” Zimmerman says. “In his youthful letters to Washington, he’s a sassy firebrand. And he keeps that fire in his belly for idealistic causes. He sees that things are so calcified, in terms of the social and political order. He senses that through the spread of what we would call ‘Enlightenment values,’ a new world is being created.”

The image of Lafayette as a sassy firebrand has a certain appeal for Peter Godziela ’25, a graduate of Lafayette College and Lafayette Elementary School in his hometown of Chatham, N.J. For Facing Lafayette: Man, Myth, Image, a campus exhibition that runs through the fall semester, he helped contextualize representations of the Marquis de Lafayette from the College’s holdings.

Several works depict Lafayette in his American Revolutionary War phase. A much later one shows him in a prison cell with Adrienne and their two daughters. With Lafayette’s involvement in the American and French Revolutions, Austrian authorities had viewed him as a threat to their own monarchy. Among the College’s Special Collections items is the sword he was bearing as he was captured by them.

That range of life experiences and emotional states—youthful optimism as he looked to adventures ahead, unbroken determination in dark times—makes him an inspiration, Godziela says. “What does it mean to be successful? What does it mean to be driven by idealism, to stand by the things you believe in, and at the same time to be putting yourself out in the world?”

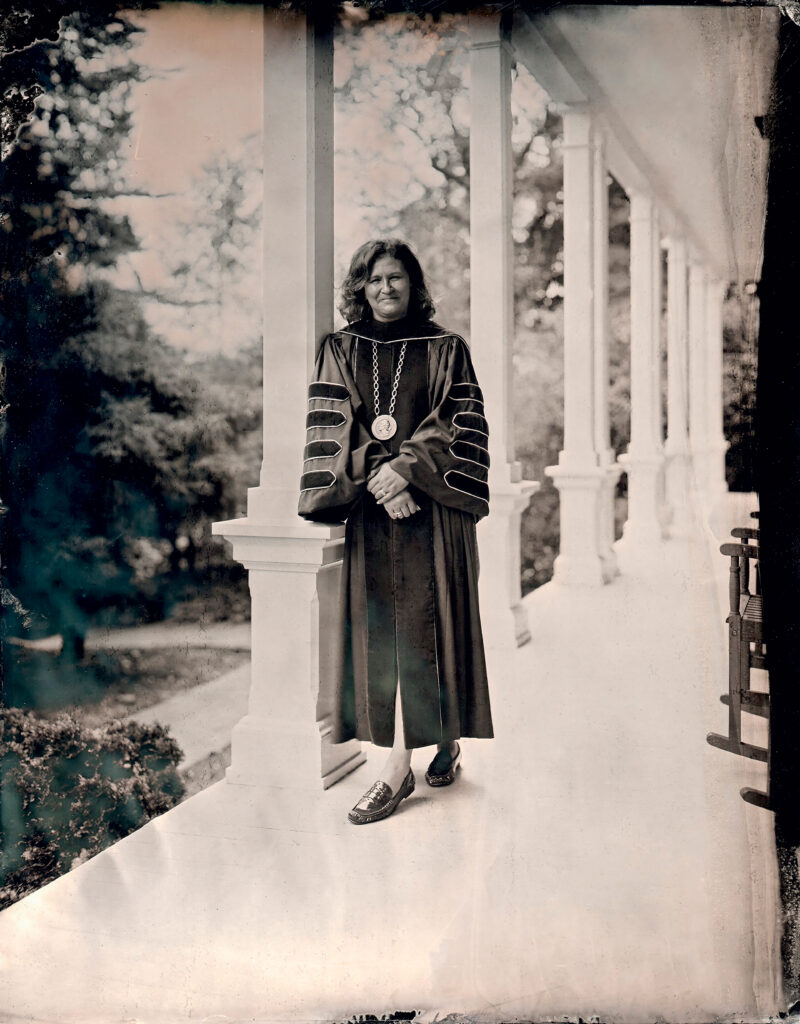

All of which is to wonder: What does “Cur Non?” mean in the life of Lafayette College? To Nicole Hurd, Lafayette’s president, it’s “a beautiful call to action.” (Hurd is a close friend of Hamilton’s Daveed Diggs, who has twice visited the campus and is a board member of the College Advising Corps, which Hurd founded.) “It fits an academic institution well. The undergraduate years should be animated by curiosity, whether that curiosity drives a student to write a poem or to mix solutions in a chemistry lab.”

“Why not be bold? Why not work to heal this world? Why not go places where people haven’t gone before?”

Hurd likes the “and” conjunction, as in liberal arts “and” engineering, or academics “and” athletics. “Cur Non?” fits right into her system. “It calls for both theory and practice. Academic rigor is a huge part of what characterizes a place like this. But then there’s the application of knowledge.”

“Cur Non?” is also an organizing question for how to live a life, she says. “Why not be bold? Why not work to heal this world? Why not go places where people haven’t gone before?” The College’s namesake “lived a life of service, a life of impact, and that’s very much part of our DNA as an institution. It’s about embracing something bigger than yourself. What an incredible example for our students.”

That institutional DNA helps define the College’s concept of its future. The recently adopted strategic plan calls for closer connections to the city of Easton, whose citizens founded the College in gratitude to the fighting Frenchman. The plan also identifies as a key theme the study of democracy and its technologies, including how to support “democratic practices and discourse.” In Hurd’s view, the Marquis would eagerly join in such an enterprise.

Above all else, she sees in the story of the Marquis an illustration of a consequential life, in all its complexities. “We hope our students will thrive and blossom,” she says. “We also hope that they will be challenged. Hard things are part of growth, part of the journey.”