The French Marchioness

When artist Audrey Flack taught at the College a decade ago, she learned about the remarkable—yet often untold—story of Lafayette’s wife, Adrienne. Enamored by Adrienne’s spirit, Flack worked to honor her through a bronze sculpture, set to be installed on campus during the spring semester.

In creating the clay mold of Adrienne, artist Audrey Flack studied iconic images supplied to her from Skillman Library’s Special Collections. Flack meticulously considered every detail: the curl of her hair, the contours of her nose, the angle of her head, and the graceful sweep of her 18th-century bodice.

Photograph by adam atkinson

During her residency at Lafayette in spring 2015, American artist Audrey Flack couldn’t help but notice all of the grand imagery devoted to the College’s namesake.

The bronze-cast Marquis de Lafayette, standing with youthful confidence in full 18th-century military regalia at the south entrance of Colton Chapel, sword drawn and tipped downward, his ribboned tricorn hat tucked at his side. And there was another statue, of similar posture, in light-colored limestone at the back of Hogg Hall. The major general’s presence appeared in portraits, busts, statuettes, and signage in academic and administrative buildings across campus.

As she walked the campus, Flack, known for her deep concern with the historical place of women and their representations in the arts, noted the absence of works dedicated to Lafayette’s wife, Marie Adrienne Françoise de Noailles.

The French noblewoman, born in 1759, married the College’s namesake in 1774; Madame de Lafayette would make a lifelong commitment to the cause of human rights, just as the Marquis did.

Married 33 years, the couple worked in partnership to help abolish slavery and establish social justice and religious freedoms. They survived separate imprisonments, hundreds of miles apart during the French Revolution, and with Adrienne’s tenacity after her release found their way back to each other.

Their lives were with purpose, each one establishing their own rightful place in history.

Transcendent connections

Flack, then in her 80s, grew so interested in Adrienne’s life that she went to Special Collections to search archival information and view historical images.

Her fascination with Adrienne would develop into an obsession, drawing in key experts of the Lafayette community who helped to support this late-career surge in creativity. Returning home to Manhattan after serving as the Richard A. ’64 and Rissa W. Grossman Artist in Residence on campus, Flack, revered for pioneering public sculptures and photorealist paintings, had become so engrossed in Madame de Lafayette that she immediately created a clay bust of her. She later turned this work (pictured below, on left) into a self-portrait, a sign of her identification with Adrienne.

In December 2023, Robert Mattison, Metzgar Professor of Art History Emeritus, who helped bring Flack to Lafayette, arranged a meeting between the artist and President Nicole Hurd, sensing they’d enjoy each other’s shared interest in sainted women and sainted mystics, an area of academic focus for President Hurd, who has a Ph.D. in religious studies. Mattison also wanted her to see the clay model and consider including the work as part of the College’s Bicentennial celebration.

An immediate personal and intellectual connection between them blossomed as they talked in Flack’s Upper West Side apartment, as if they’d known each other for years. “The same energy and light you see in her art was revealed in her spirit,” Hurd recalls. During the hourslong meeting, they engaged in deep conversation about the feminine and the divine.

That meeting ultimately led to the Bicentennial Art Commission to pursue a much bigger dedication to Adrienne: a bronze bust, 42 inches tall and 36 inches wide, and weighing 350 pounds.

Based on iconic images of Adrienne and biographies of her life from the Special Collections and College Archives, Flack last year completed a maquette of Adrienne, who is represented in her 20s, eyes gazing downward, in the early years of her marriage to Lafayette. She worked on the bust at all hours of the day while communicating regularly with Mattison, a friend and confidant for decades.

He’d often receive lengthy midnight emails from Flack describing her creative thoughts and processes, including a particularly touching one excerpted here: “Dear Bob, I had to stop, tear myself away from Adrienne and jot down my thoughts. Last night she let me sleep, the two nights before she woke me up at 2:30 in the morning telling me what to do. I feel like I’m channeling her. The collar above her bodice needed to be extended, and she needed shoulders. By 4:30 a.m., I had blocked out a rough version of shoulders and draped collar, but then, of course, she needed arms. By 8:30 in the morning, I could see she was in good enough shape for me to let go and get some rest. The entire process is exhausting, yet it’s extremely exhilarating when a work of art gets to this state, where every mark, touch, accent, dent, curve, twist of the lip, look of the eye, matters! The whole piece comes alive. That’s what happens when you hit it. She sings!”

Flack’s commitment to accuracy in her depiction of the young Marquise was remarkable. “She studied every representation of Adrienne I could locate in published sources and engravings from our collections,” says Elaine Stomber ’89, P’17,’21, co-director of Special Collections and College Archives and College Archivist. “The curl of her hair, the design of her bodice, and the shape of her nose were carefully considered and reworked countless times.”

The piece would become Flack’s last major work before she died, at age 93, in June 2024. Flack continued to communicate regularly with her Lafayette College colleagues as she refined her sculpture, right up until the end. Before Flack’s passing, the project was transferred, per her wishes, to sculptor Brian Booth Craig, Flack’s longtime assistant, who specializes in bronze. Now ready for final casting, the bust will be installed in the area of Skillman Library and unveiled during the Council of Lafayette Women Conference March 7, a biannual event celebrating the contributions of women to the College.

Gilbert and Adrienne

When the time came for the powerful Duc d’Ayen, scion of the House of Noailles, to consider potential husbands of acceptable means and social status for his five smart, independent, and highly educated daughters, he already had an eye on Gilbert du Motier—better known as the Marquis de Lafayette. An orphan by the time he was 13 in 1770, Lafayette was already in the King’s Musketeers and came from a long line of French patricians.

Diane Shaw, College Archivist Emeritus, who has written and spoken on Adrienne’s life, says it was a perfect match for contracted 18th-century nuptials among French nobles. And so, the duke arranged for his second daughter, Adrienne, to marry Lafayette, even though his wife, the Duchesse d’Ayen, didn’t think much of the lad, seeing him as cold and aloof and far too young to marry.

Her opinion of the young Lafayette quickly evolved, as she discovered in him “the most active spirit, the firmest character, and the most passionate soul.” In fact, Shaw says, the duchess spilled the news about the engagement early, much to Adrienne’s delight. The couple married April 11, 1774, at the family’s estate in Paris. Adrienne was 14, Lafayette 16.

“It was a love match, and she clearly adored him,” even though the union represented a step down in social position for Adrienne, Shaw says, describing the immense wealth of Adrienne’s family. “The family home, which still stands in Paris, takes up several blocks.”

After receiving a promotion to captain in his father-in-law’s regiment and the birth of the couple’s first child, Lafayette sailed off to fight in the American Revolution. A heartbroken Adrienne, pregnant with their second child, described her husband’s decision to leave without notice as a “cruel departure.”

Perhaps mindful of his impulsive actions, Lafayette took time to write to Adrienne, often keeping things light. Shaw always smiles at his amusing letters dismissing the leg wound he received at the Battle of Brandywine while recuperating with the Moravians in Bethlehem.

She adds that, as time passed after the war in America, the couple became involved in the antislavery movement and purchased a plantation at Cayenne in the French colony of Guyana in South America. “Lafayette wanted to try an experiment that would lead to the gradual emancipation of enslaved Africans,” Shaw notes. “Adrienne was part of that, too, and deserves credit for supporting it. As the French Revolution started to absorb Lafayette, she took over corresponding with the plantation managers and made arrangements with a local seminary to care for the religious welfare of the enslaved people. Adrienne also supported Lafayette’s efforts to secure rights for French Protestants.”

Returning to a restive Paris, Lafayette, affectionately known as “father-provider,” oversaw the police and military, while Adrienne, called “universal mother,” organized collections for the poor and mourned those who perished in the storming of the Bastille.

Shaw notes that Lafayette’s support of a constitutional monarchy ran afoul of the more radical leaders of the revolution and he was forced to flee France in late summer 1792. He had hoped to reach England, but the Austrians, at war with France, captured him at the Belgian border. He was jailed for nearly five years.

Adrienne soon faced peril herself and was arrested in 1792 and jailed in 1793 during the Reign of Terror, Shaw says, noting that her grandmother, mother, and her sister were executed. Only intervention from Gouverneur Morris, the U.S. minister to France, spared Adrienne from the guillotine. On release from prison in 1795, she immediately made plans to seek her husband’s freedom.

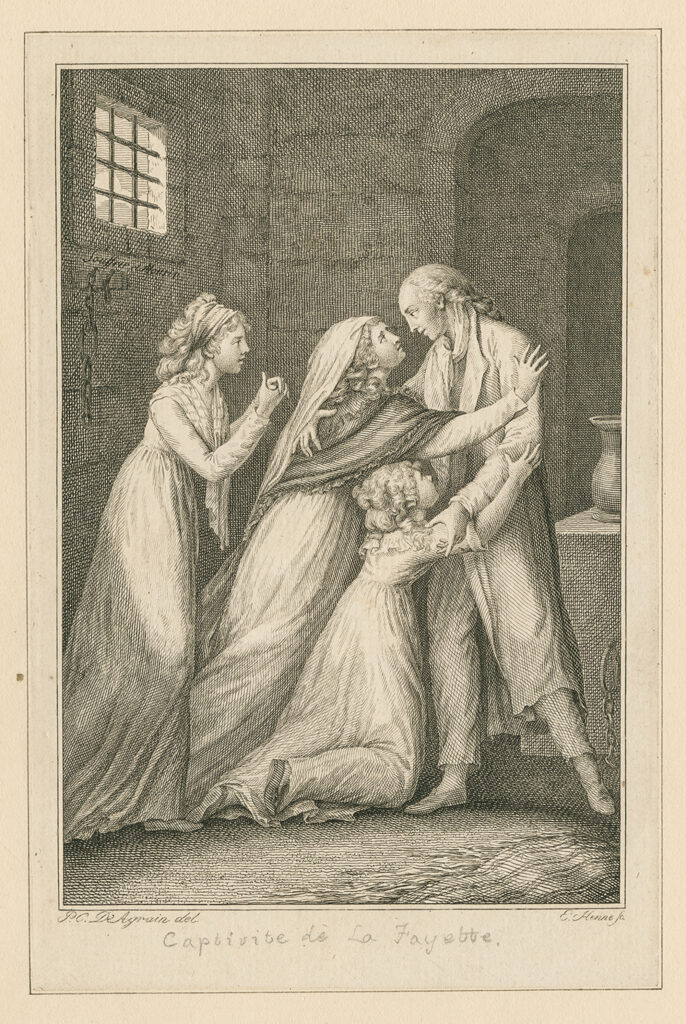

Mattison points to a dramatic engraving of Adrienne’s reunion with her husband in Olmütz prison in Moravia (now the Czech Republic), where Lafayette was being held by Austrian authorities. Adrienne and their two daughters had chosen to accept imprisonment during his last two years of captivity to be by his side. “Audrey recognized the poignancy of this scene as she worked on her sculpture. It captures Adrienne’s sense of dignity, propriety, strong intellect, and place in history,” he says.

“The Lafayette family became celebrated internationally as the prisoners of Olmütz until 1797 when Napoleon Bonaparte negotiated the family’s release,” Shaw says.

While in captivity, Adrienne secretly penned a memoir about her late mother by writing in the margins of another volume, using toothpicks and ink. When she was released and returned to France, she found a press to privately print a select number of copies of the manuscript in 1800. (There are only two known copies in the United States, and Lafayette College owns one of them.)

Unfortunately, the poor conditions Adrienne experienced in the Olmütz fortress ultimately led to her permanent decline in health. She died on Christmas Eve 1807, surrounded by her family. Her final words were for Lafayette: “I am yours alone.”

In a letter to his old friend, the writer, Madame de Staël, Lafayette wrote “the incomparable woman whom I married when I was 16 and she was 14 was so deeply fused into my existence that it was necessary to have lost her in order to know what part of myself would cease to live.”

Photograph by adam atkinson

“I can hear her voice.”

In his remote studio near East Stroudsburg, Pa., Craig spent much of the summer finalizing the clay mold and preparing it for the foundry where molten bronze will fill a crucible for the final pour.

Using Flack’s wood-handled shaping tools, each bearing her name and with a patina from years of use, he would make the gentlest of strokes to shape a lock of hair or lace on Adrienne’s gown.

He first met Flack in 1994, when he was a graduate student. Familiar with her every instinct, he completed her final work of art with the utmost sensitivity.

“I’ve been having conversations with her the whole time,” he says. “I can hear her voice, which has guided me. One of the challenges we face with this project is that we have very few source materials about what Adrienne looked like, which is OK, because Audrey had a way of really encapsulating the spirit of the person.”

Craig remembers Flack telling him with urgency about how he would have to finish her work on his own, without her oversight, never considering that she may have been sensing her end.

“Audrey was a prominent fixture in the art world for more than 60 years. I could only assume she’d be around forever,” he says, stepping away from the final clay mold. “In these final months working on Adrienne, it hits me—this is the last time I will get to work with Audrey. But what an honor to shepherd this through to the end, a significant work that will hopefully speak to generations of students and anyone in its presence at Lafayette.”

“This magnificent final work by Audrey Flack allows us to commemorate Adrienne Lafayette and her strength and courage in the face of hardship, and think about what she means for Lafayette College and what it meant for the Marquis to have Adrienne as his wife,” Hurd says. “This sculpture serves as inspiration for the role of women at Lafayette and in the greater world. As we lift up the Marquis de Lafayette as the inspiration for the founding of the College, we also lift up Adrienne and Audrey, and their contributions. It is an incredibly important historic and artistic moment.”

In all of her research on Madame de Lafayette, Shaw says it’s her courage and care for people that stand out as virtues that should be admired and emulated today.

“Despite her privileged upbringing, she was a modest, warm, and loving person with a spine of steel,” Shaw says. “She stared death in the face, and after her own incarceration went to save the man who stood for liberty and human rights. It’s no surprise that everyone who studies Adrienne is moved by her remarkable life story. And now she will have a permanent place on the campus.”

WHY BRONZE?

Bronze has been used by sculptors for thousands of years, ever since the ancient Greeks and Romans recognized the versatility of the alloy to create public works of art to honor its most important military and political figures.

Artists working on outdoor statues have historically turned to bronze, a mix of predominately copper with tin and zinc, because of its strength and its anticorrosive properties, making it resistant to the ravages of weather. It’s malleable and easy to cast, sculpt, and clean, and can last for thousands of years.

Artist Audrey Flack’s sculpture of Marie Adrienne Françoise de Noailles first came to life in bronze form in April with the casting of the smaller 25-pound model at Independent Casting Inc., a fine art foundry in Philadelphia. They’ve produced bronze artwork on other figures from history, including George Washington, Frederick Douglass, and Clara Barton.

Bronze ingots were placed in a graphite crucible, heated to 2,200 degrees Fahrenheit as foundry staff in heavily padded protective aprons tipped the vessel and poured bright, silky molten bronze with the consistency of whole milk into a ceramic mold. The steady work was performed on a floor covered with sand, to catch any dripping of molten bronze. Fiery liquid filled the space as a distinct smell of burnt metal lifted in the air. As the mold was broken, the bronze was released as a brownish hue and awaited final polishing after its cooling.

Photograph by adam atkinson