The Hubble Space Telescope has been in orbit since 1990, capturing stunning images like this star cluster and its surroundings. PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF NASA, ESA, THE HUBBLE HERITAGE TEAM (STSCI/AURA), A. NOTA (ESA/STSCI), AND THE WESTERLUND 2 SCIENCE TEAM

Easton to the stars

A small company run by three generations of Lafayette alums has had an enormous impact on helping NASA achieve its missions in space.

by Michael Blanding

In July 1969, all eyes in America were turned upward for the Apollo 11 mission, mankind’s first attempt to land astronauts on the moon.

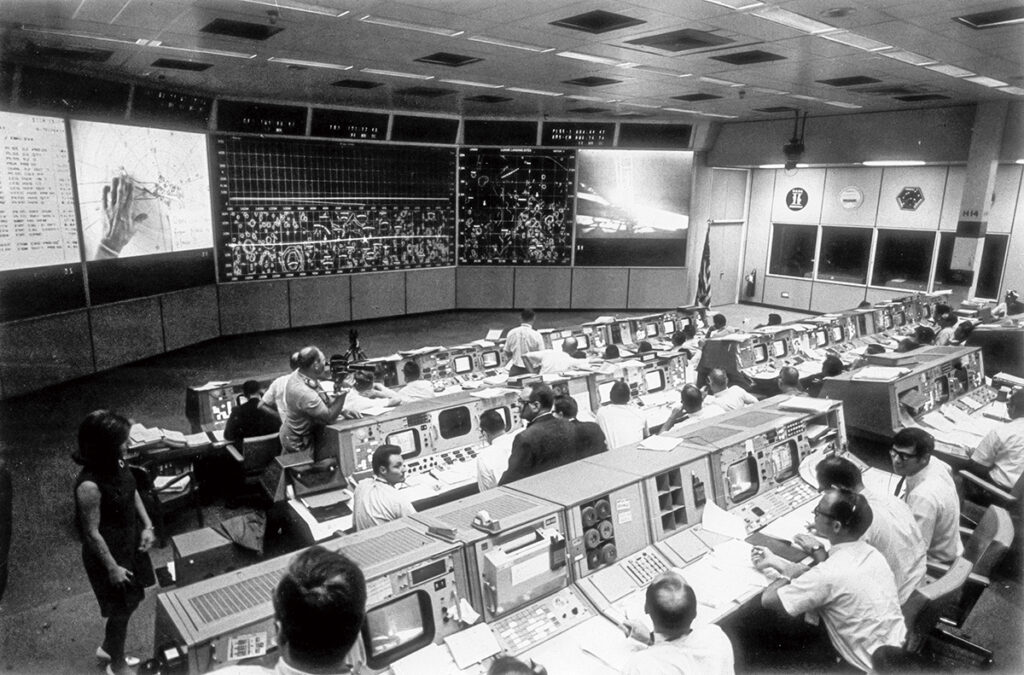

A rocket was slingshotted around Earth into lunar orbit before sending a lander to the surface, where two astronauts took the first steps on lunar dust. Not everything went well, however. Due to miscalculations, the lander missed its original landing site, having to make an emergency landing with just 20 seconds of fuel remaining. As 60 million people watched tensely from Earth, mission control in Houston beamed communications into space to guide the astronauts to safely recover the lander and bring the crew home.

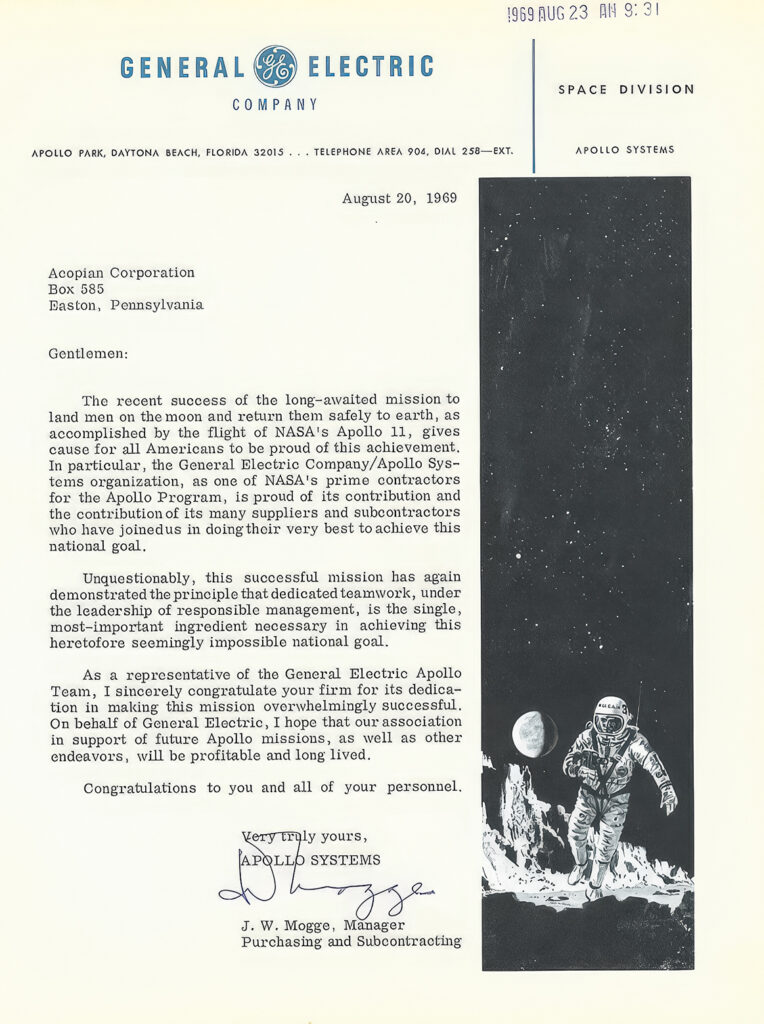

The mission was a massive undertaking, led by NASA and involving dozens of contractors around the world. Those contractors included a small family-run company in Easton, Pa., called Acopian Technical Co., which provided the crucial power supplies for the electronics at mission control, allowing for the operation’s success according to a grateful letter written by lead contractor General Electric. “The recent success of the long-awaited mission to land men on the moon and return them safely to earth,” it read, “gives cause for all Americans to be proud… I sincerely congratulate your firm for its dedication in making this mission overwhelmingly successful.”

Today, the letter is one of the company’s prized possessions. “This was a crowning achievement,” says company president Alex Karapetian ’04, “where we helped save the day.” Acopian provided power supplies that successfully drove not only NASA’s moon mission: It also has provided power supplies to all 10 NASA field centers in the United States, as well as multiple smaller facilities and subcontractors, for more than 70 years. It’s safe to say Acopian has been involved in every major NASA mission during those years. This also includes the upcoming Artemis II mission, which is expected to launch from Florida next year, sending astronauts back to the moon for the first time in decades.

The relationship with NASA also attests to the legacy of Lafayette, as three generations of family members have graduated from the College and applied their technical know-how to create power supplies advancing the space race—including Sarkis Acopian ’51, his sons, Greg Acopian ’70 and Jeff Acopian ’75, his grandson Ezra Acopian ’03, and his grand-nephew Karapetian. In their unassuming way, these family members represent the best of the American dream, beginning with a self-made immigrant who succeeded through the ups and downs of economic and technological change by focusing on the old-fashioned values of providing reliable products and superior service.

Three days or less!

Sarkis Acopian was born in Iran to Armenian parents and was ambitious from a young age. When a couple of American soldiers told him that Lafayette was a great engineering school, he came to Pennsylvania in 1945 determined to start his own company making inventions. “People in college laughed at him at the time,” says son Jeff. Drafted twice during his time in college, including a stint at a Texas Air Force base, he graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering in 1951 and began working at an electronics company in New Jersey, where he designed products including a power sander and soldering iron.

Set on being his own boss, Sarkis left a few years later to open Acopian Technical Co. in Phillipsburg, N.J., just across the Northampton Street Bridge from Easton. “He was doing shop-jobbing, making whatever anybody needed, electrical or mechanical,” Jeff says. His mind rarely stopped working, even at night, as he spent time tinkering with equipment on the living room floor. Among other products, he created the first radio run on solar power in 1957. According to Jeff, a Japanese customer purchased one with a pearl.

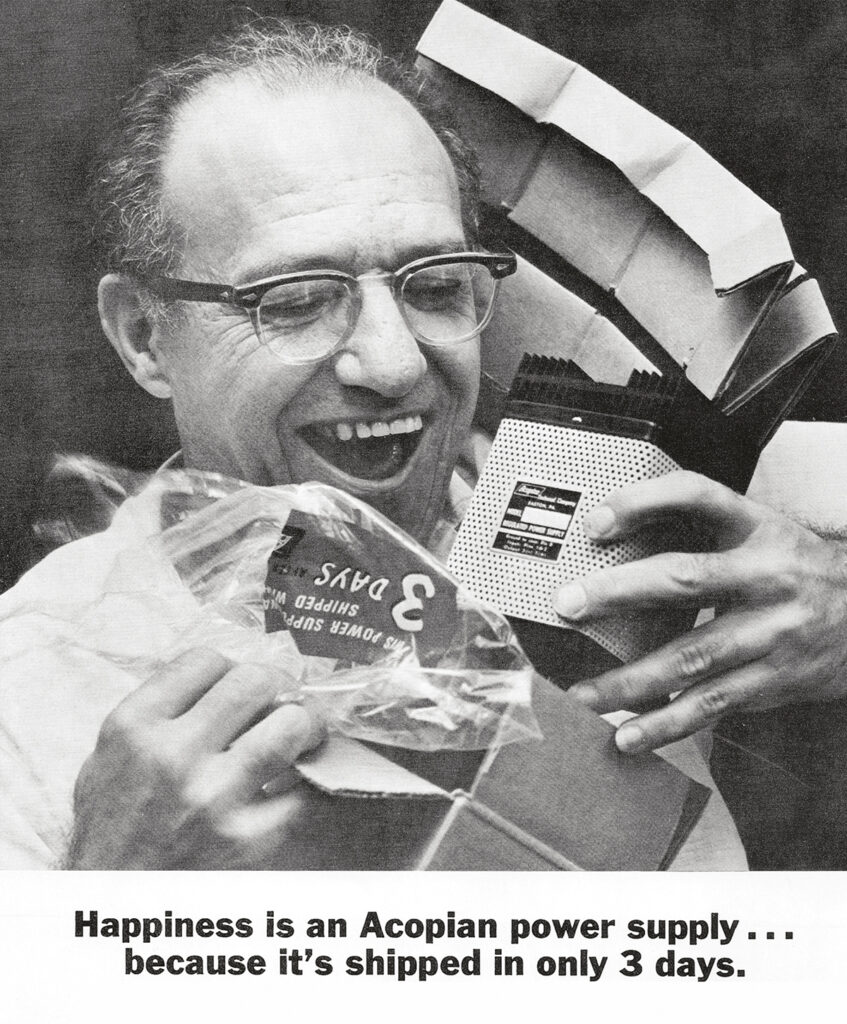

By the time Sarkis relocated his company to Easton in 1958, he had realized that the bottleneck for many of the products he was making for customers was the power supply, the component that converted the alternating current from the wall socket to direct current a device could use. “He’d make what was asked and then had to wait six weeks for a power supply to be delivered,” Jeff says. So he started making his own power supplies, and in 1963, made an audacious promise: He would make and ship any power supply in three days. That timeline was unheard of then, and is even rare today. “Nobody else could do it.”

Jeff has one word to explain how the company has been able to pull off the feat—efficiency. His father set up a system in which not only were all the parts available to build power supplies, but each person in the process was aware of where parts were coming from and where they were going so they could assemble the design quickly. This quick turnaround put the company on the map, along with cheeky advertising such as one 1965 ad that showed the close-up of an engineer with rimmed glasses and a goofy smile unwrapping one of its products along with the tagline, “Happiness is an Acopian power supply.”

While modeling efficiency in the business, Sarkis had a daredevil’s spirit outside work. He scuba dived in quarries in New Jersey and jumped from airplanes with an old WWII style parachute, completing more than 250 jumps in the early days of skydiving as a sport in the 1960s. In 1971, he opened a manufacturing facility in Melbourne, Fla., coincidentally near the newly constructed Kennedy Space Center, and flew the company-owned Cessna back and forth to Pennsylvania. A year later, Acopian power supplies were used to send communications when President Richard Nixon made his historic trip to China.

Both of Sarkis’ sons followed in their father’s footsteps by attending Lafayette, earning degrees in electrical engineering—and also inheriting his love for thrills. Older son Greg became an avid surfer of the New Jersey coast during his time at college, before working at a radio station after graduation. Jeff also surfed and played acoustic guitar along with Dave Farer ’75 in a group called “It’s Not a Hoagie.” Most of the duo’s music consisted of original compositions, with a few Beatles, Grateful Dead, and Allman Brothers songs thrown in. (Parts of their last performance, at Sigma Nu fraternity in 1975, are on YouTube.) He traveled for several years after college, building satellite antennas in Nigeria and repairing computers in California before returning home. Both sons began working at the company’s Florida facility in the early 1980s, surfing while they climbed the rungs of the firm. By the late 1990s, Greg had become president and Jeff vice president. Now they are both co-chairmen.

Over the years, the company has cranked out more than 7 million power supplies. “Our client base consists of everyone from the guy working out of his garage to Fortune 500 companies,” Karapetian says. Acopian power supplies have run rides at Disney World, dropped the New Year’s Eve ball in Times Square, and supported audio production houses for Grammy-winning artists and cameras at the Super Bowl. In all that time, says Jeff, “we’ve never missed a ship date. Never.”

Along with its off-the-shelf systems, Acopian also produces custom-designed power supplies no one else makes. “Standard voltages are 12 or 24 volts—a lot of companies can make that,” Karapetian says. “But they can’t give you a 17- or 62-volt unit. We can do anything from practically 0 volts to 30 kilovolts.” At the same time, the company can make units to fit into unusual spaces and customize them with switches and colored LEDs to a customer’s content. For the more complicated custom units, Karapetian says, time to build and ship might rise from three days to a maximum of three weeks, but that’s still light-years ahead of competition. “Other guys would take three months.”

Also making Acopian unique is the fact it services all of the power supplies it’s ever made, even those made decades ago with vacuum tubes. “We get power supplies that are 20, 30 years old that we fix and send back to the customer,” Jeff says. Last year, for example, a NASA engineer called about a system the company developed in 1979—46 years ago—assuming he’d need to replace it with a newer system, and was shocked to find the company could build him the exact same system, avoiding a costly retrofit.

A legacy in space

NASA started using Acopian power supplies early in the company’s history, and after a positive track record, soon expanded to using them in all of its facilities. While the company’s products have not gone into space, they’ve been used for R&D, prototyping, and testing of spacecraft and vehicles, as well as for mission control and ground support. Karapetian

remembers seeing the 2016 film Hidden Figures about female mathematicians who planned the early spaceflight missions, and feeling a swell of pride in the scenes featuring mission control, with rows and rows of technicians sitting at throwback computer terminals. “I just thought, ‘Oh my God, this is what our power supplies are doing. They’re using them in that control room,’” he says.

In 1995, Acopian provided crucial support to the Hubble Space Telescope, a high-resolution telescope launched in 1990, which orbits Earth, providing stunning images and other data that have led to crucial breakthroughs in astrophysics. When engineers were attempting to test an electronics package astronauts would soon bring to the telescope to replace outdated equipment, a 24-volt power supply failed. The project lead at the time, Mike Miskowski from Lockheed Martin Missiles and Space Co., phoned the original manufacturer, only to find it would take five weeks to replace. He then, on a Monday afternoon, called Acopian, who promised a replacement supply could be shipped in less than three days. In fact, he received the device Wednesday morning.

“I thought I was grateful beyond description,” Miskowski later said in a letter to the firm, “but I was to become even more grateful.” While replacing the 24-volt supply in the test console, the disturbance caused an adjacent 5-volt supply to go out. Acopian shipped another one that same afternoon, this one arriving by Friday. “I, and the entire Hubble Space Telescope program would like to express our extreme gratitude to you and your company for remembering the days when ‘service’ meant going one step further than the competition and attempting to support the customer in every way possible,” he wrote. “We stand in awe of your ability to step outside the ‘normal’ system and support your customer in time of need.”

Service like this has kept NASA and its contractors loyal customers for decades. “They ship quickly, and their stuff works,” says David Van Gilst, lead systems engineer at the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute, who has used Acopian power supplies for missions aboard NASA’s science fleet. “I have had zero failed Acopian power supplies out of the 100 or so I’ve touched over the last two decades,” he says. Acopian, Van Gilst says, has even taken back products when he’s inadvertently given the wrong specs, replacing them “quickly and for a reasonable price.” Bottom line, “the less time I spend dealing with a failed power supply, or equipment that no longer works because of a failed power supply, the more time I can spend on my actual job.”

The most recent generation of family members to join the company include Greg’s son Ezra, who majored in religious studies as an undergraduate before continuing his education at Eastern Florida State College, where he took several electrical engineering courses. “He has a very strong mechanical aptitude—it just comes naturally to him,” Karapetian says. After college, he worked at a conservatory in Texas before coming to work at Acopian’s Florida facility. He worked his way up from a warehouse stocking position to purchasing before becoming CEO in 2020.

Karapetian took a less conventional path, studying government and law at Lafayette and moving to D.C. to work for a lobbying firm after college. While home for the holidays in 2005, he helped out at the family business and found he enjoyed it more than his current work. “On my second day, I took a sales call and sold a power supply—and I didn’t even know what we sold,” he says. “I really loved sales and talking to people.” He called his uncle, Jeff, a few months later, asking if he could come work for the company. From there, Karapetian worked his way up through sales to VP of sales and marketing, before becoming president five years ago.

Now the Easton headquarters, located next to Easton Area High School, offers R&D and custom designs, while most products are mass-manufactured in Florida. An entrepreneurial mindset still runs in the family: Natalie Acopian ’19 started a women’s clothing boutique in Greenwich Village called Colorful Natalie.

After stepping back from the company, Sarkis gave freely to philanthropic causes, including funding for three churches and a number of other buildings that bear his name all over the Lehigh Valley, as well as funding a field guide to birds in Armenia and making the single largest donation to the World War II monument in Washington.

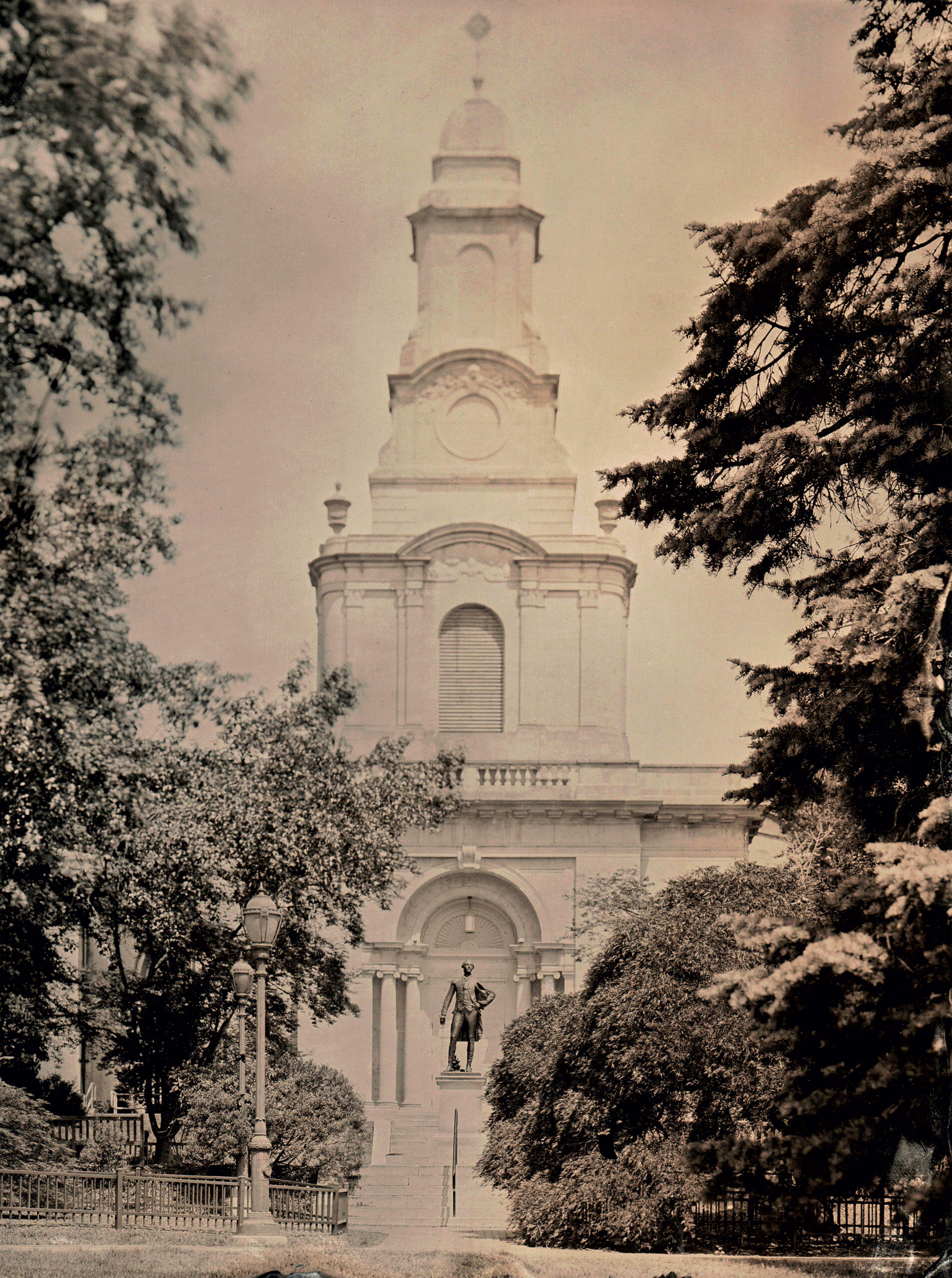

In 2002, he approached Lafayette about making a major donation to the College, which took the form of the Acopian Engineering Center, a 90,000-square-foot facility that opened in 2003. After Sarkis’s death in 2007, Acopian has continued to support Lafayette, sponsoring the school’s motorsports team and events on campus. “Lafayette is part of our DNA—it’s our extended family,” says Karapetian, who was president of the Alumni Association and now serves on the Board of Trustees.

Back to the moon

In addition to other support, Acopian has also welcomed many other Lafayette students and grads as interns and employees. Bill Hoffman ’10 started as an intern after his sophomore year and came back after junior year as well, seeing the hands-on experience as a perfect complement to his electrical engineering degree. “Doing assembly and testing is not something you see at school,” he says. “You are taught to design things but you don’t see the people on the floor actually putting them together and what their challenges are.”

He now works at Acopian as an engineer, doing custom work in the Easton office. Among other systems he’s helped design was one for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., to test vital components of the Perseverance rover, which went to Mars in 2021, sending back jaw-dropping photos and videos of the red planet. “We got to go to Pasadena to meet with the team face-to-face and see how they were using our products to power the vehicle to do whatever testing they needed to do,” Hoffman says.

In addition to NASA, Acopian has recently expanded its footprint in the space race with power supplies for private companies SpaceX and Blue Origin, which are each hustling to launch manned and unmanned missions to both the moon and Mars. When Karapetian first got an order from Blue Origin, he remembers, he’d never even heard of the company. “Then within a matter of years, it had expanded and had several successful missions,” he says.

According to Blue Origin instrumentation and controls engineer Jarad Neal, the company uses Acopian power supplies in the majority of its testing systems, powering sensors such as pressure transducers, which convert pressure into an electrical signal. “Just one of our test stands can have a thousand or more of these sensors,” Neal says. “Their performance has been something that we have come to rely upon.” Like other customers over the years, he’s been impressed with Acopian’s fast service. When a power supply for an energetics test at a West Texas site failed, he sent it back to Acopian to have it examined. “I had the supply roundshipped from my desk to Acopian and back in less than a week, ultimately saving the schedule for a project that was already in jeopardy of slipping,” he says, noting that this kind of turnaround was remarkable for factory repairs.

“We are honored and excited to align ourselves with NASA,” Alex Karapetian says. “Our small company is able to have a gigantic footprint.”

Karapetian is proud that no matter who ultimately succeeds in the space race—NASA, SpaceX, or Blue Origin— they’ll use Acopian products to do it. “It’s pretty cool we’re the constant between them,” he says. “We’re not choosing any of them—we’re choosing all of them!” Artemis II is currently using Acopian power supplies to test its new Space Launch System, which will propel its Orion spacecraft to orbit the moon, the first manned flight there in more than a half-century. If all goes well, then Artemis III will attempt a new moon landing, currently scheduled for 2027.

If it does, it’s certain Acopian will aid in that adventure, powering the mission control that enables the spacecraft to succeed. “We are honored and excited to align ourselves with NASA, who we’ve been supporting for decades, and to know they chose a family business from eastern Pennsylvania,” Karapetian says. “From our small company, we’re able to have a gigantic footprint—and that’s extremely inspiring and meaningful.”