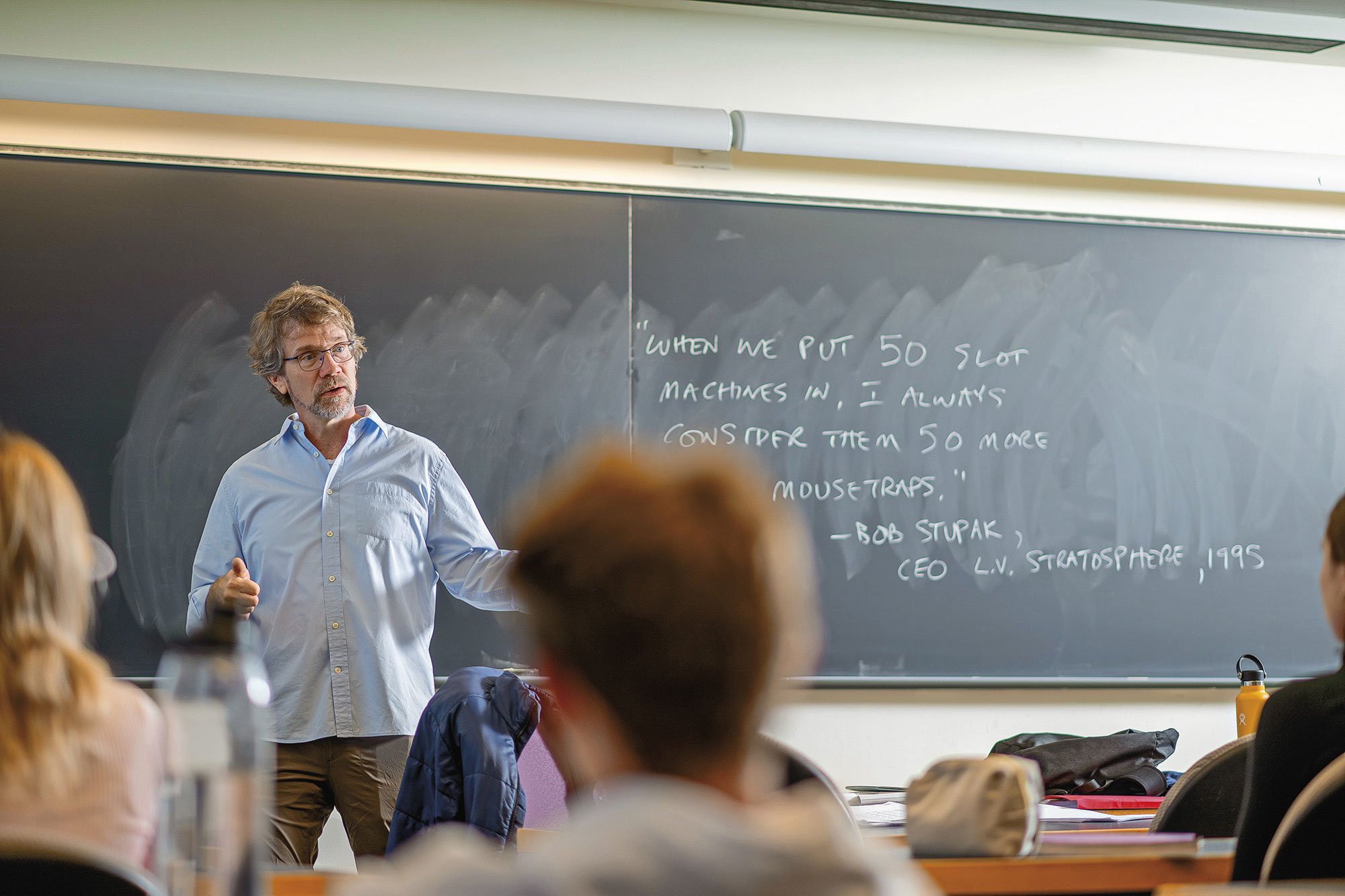

Exploring the odds

Prof. Derek Smith and his students unpack the high-stakes world of gambling

Photographs By Adam Atkinson

Lottery tickets, sports betting, and a trip to the casino—it may read like the schedule of someone pressing their luck, but it’s actually the syllabus for the First-Year Seminar “Gambling: Here & Everywhere” with Derek Smith, professor of mathematics.

This seminar, versions of which Smith has taught for nearly two decades, investigates the social, economic, and psychological impacts of gambling. “The motivating question for the course is whether the proliferation of gambling in its various forms is good for society,” Smith says.

When the Supreme Court overturned the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act in 2018, opening legal and regulated sports gambling to all states, the subject matter in Smith’s course became even more relevant.

“It’s now as easy as a ‘click’ to legally wager on sports, and not just on whether a team will win by a certain number of points, but also on whether individual players will perform at certain levels,” Smith says. This outside expectation to win—games, money—has placed added pressure on athletes across the country, including those on college campuses. He explains that the nature of sports gambling can more easily lead to student-athletes being targeted or harassed. What’s more, according to the NCAA, one in three student-athletes have experienced betting-related harassment.

Gwen Cahill ’28, who is taking the seminar this fall, was sympathetic to learn about student-athletes being caught in the crossfires of gambling. “It’s a lot of pressure for them to know they have money being placed on them,” she says.

Another sobering statistic: University of Buffalo reports that 10% of college students have a gambling disorder. So as Smith’s course explores ethical concerns, it also exposes the dangerous dimensions of gambling. “Are there ways to better protect students and student-athletes from these harms?” he asks.

For example, Smith has students consider how state lotteries might affect low-income citizens. According to a 2022 study from the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism, University of Maryland, lottery retailers in almost every state are concentrated in neighborhoods that are disproportionately home to Black, Hispanic, or low-income residents. He explains that these lotteries tout state benefits, such as revenue being earmarked for good causes like public education. “But, in the end,” he says, “the effect is a relatively small source of state revenue that takes a disproportionately large share of money from communities that tend to be poor, non-white, and less educated.”

Through class discussion and writing assignments, students are tasked with developing their own takes on the state lottery business. The first assignment asks students to evaluate whether or not a state without a lottery—Alaska, Alabama, Hawaii, Nevada, and Utah—should implement one.

Makenna McCall ’27, who took the course last year, focused on Alabama. “I was surprised by how interdisciplinary the project was,” McCall says. “We had to take the time to learn about some of Alabama’s specific cultural influences, and economic and political issues that the state is facing.”

Two-thirds of the way through the course, students take a class trip to Turning Stone Resort Casino in Oneida, N.Y. In the weeks leading up to the excursion, students complete a project pitching a new casino game to executives. To successfully do so, they must include an analysis of how much “the house,” or the casino, will make back on every dollar spent.

“Doing this assignment means realizing that the house edge is an integral part of how gambling works,” McCall says.

Participating students each receive $25 of “free play” with which they can demon-strate their newfound understanding of the casino system.

“The students have thoroughly studied casino and game design, which is per-fected to extract the maximum amount of money from players over time,” Smith explains. “Most of the students get back on the bus with none of their free play remaining, but with a much better under-standing of the house edge.”

Smith hopes the course will make students aware of the risks in gambling long after the class ends. “ A big motivation for me is to teach students to pause and question the propositions in front of them.”

“It may look like you have good odds, but learning the math really helps,” Cahill says. “I think it will keep me and everyone in the class from falling into games that are taking your money or that could really hurt you in the long run.”