Jan 14, 2013

Visiting Life Science Experts

“ Green Fluorescent Protein: Lighting Up Life” Martin Chalfie, winner of the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Biological…

Using bacteria to remove harmful chemicals in wetlands is the focus of research conducted by Brian Peacock ’12 (L-R), civil engineering major; Laurie Caslake, associate professor and head of biology; Art Kney, associate professor and head of civil and environmental engineering; and Andrea Mikol ’13, A.B. engineering major.

by Jill Spotz | photography by Chuck Zovko

How can signal processing be used to develop ways for the human brain to communicate with external devices? How do mathematical models enhance the understanding and control of the transmission of infectious disease? Addressing complex health issues that affect the entire world requires knowledge from many different disciplines. Indeed, they call for systems thinking — understanding how parts influence each other within a whole.

For instance, water, air, plants, and animals are inextricably connected in ecosystems. In organizations, people, structures, and procedures interact in ways that yield a healthy, successful outcome or decline and failure. “Today, the world’s most complex problems lie at

the intersection of at least two fields,” says Robert A. Kurt, associate professor of biology and chair of the College’s new health and life sciences minor. “This minor guides students in building connections between disciplines, preparing them to solve these interdisciplinary problems.”

Approved in fall 2009, the minor is rooted in the recognition of the growing importance of the interaction among natural scientists, engineers, physicians, humanists, and social scientists.

Students will be better prepared to develop more comprehensive solutions that take multiple factors into account.”

The minor provides the intellectual and interdisciplinary education and the opportunity for collaboration that students require in order to develop these problem-solving skills and bring them to a future boardroom table.

When Mary J. S. Roth ’83, associate provost for academic operations, and other members of an ad hoc life sciences committee were charged with creating a multidisciplinary life sciences program at Lafayette, they began the process with research. Comprised of faculty from biology, chemistry, computer science, electrical and computer engineering, geology, and psychology, the committee read How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School by the National Research Council. The book joins compelling research from developmental psychology, cognitive psychology, and neuroscience, pointing to ways to strengthen the connection between classroom learning and knowledge retention.

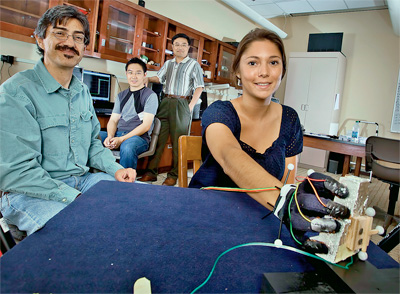

Camille Borland ’13 (right), neuroscience major, demonstrates a computerized glove used in an interdisciplinary study of human grasping behavior led by Luis Schettino (left), assistant professor of psychology, and Yih-Choung Yu (standing, center), associate professor of electrical and computer engineering. Zhao Xin Yin ’13 (seated, center), electrical and computer engineering major, also participated.

Armed with this wisdom, as well as data from faculty surveys and site visits to comparable institutions, the committee formulated a plan for the creation of a program that would prepare students to work across disciplines. “We wanted students to be able to establish connections between areas and integrate information,” says Roth.

The committee applied to participate in a three-year Project Kaleidoscope (PKAL) program on “Facilitating Interdisciplinary Learning in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) Disciplines.” PKAL has a 20-year history of assisting colleges and universities in building and sustaining such programs.

“Through PKAL we were able to connect with faculty at other institutions who were working on similar initiatives,” says Roth. “Those conversations helped us determine our goals and objectives, which in turn, assisted us in designing the best program to meet those outcomes.” The committee’s hard work paid off. Lafayette’s case study was chosen as a model of “what works” at the 2010 Keck/PKAL National Colloquium.

This project led to the first step in an integrated life sciences initiative: the health and life sciences minor. Students take courses in biology, humanities, and social science, and participate in an interdisciplinary seminar series that brings noted interdisciplinary researchers to campus.

One of the first students to graduate with the minor, Sarah Sullivan ’12 is majoring in neuroscience and is interested in pursuing an advanced degree in optometry. She was interested in the minor because of the interdisciplinary approach and the exposure to a variety of fields outside of neuroscience. “I am acquiring practical knowledge about many topics in health and am gaining a broader view of science,” says Sullivan, who looked forward to taking medical anthropology, a course that fulfills a requirement for the minor but would not normally fall under her radar as a neuroscience major.

The minor was designed to have broad appeal to students majoring in humanities and social sciences as well as those studying natural sciences and engineering. It is structured so that students experience the range of disciplines that impact decisions in the life sciences today.

“The fact that the minor is not just focused on science is extremely valuable,” explains Chun Wai Liew, associate professor and head of computer science. Liew serves on the advisory committee for the minor and was involved in the PKAL project. “This minor helps students view the world and health/life science problems through a multi-disciplinary lens. Students will be better prepared to develop more comprehensive solutions that take multiple factors into account.”

Through her experience in the Interdisciplinary Seminar Series, Carly David ’13, a biology major who is also completing the minor, is learning about current, groundbreaking research. David has met six noted researchers including Nathan Cady, assistant professor of nanobioscience at The College of Nanoscale Science & Engineering (CNSE), University of Albany. Cady spoke about his research utilizing nanotechnology — the combination of science and engineering — to identify diseases. In addition to attending the lectures, students have the opportunity to meet the researchers and interview them about their work.

“Not only are we able to hear these brilliant scientists discuss their research,” says David, “but we also have the chance to interact with them on a personal level. It has been interesting to discuss their experiences in school and to learn about what shaped their career choices. We learned that both education and experience played a pivotal role.”

Tong Pham ’13 (center), electrical and computer engineering major, Kumera Bekele ’13 (right), computer science major, and Matthew Taylor, assistant professor of computer science, discuss the use of a scribbler robot in their research on the coordination of autonomous computer programs among themselves, which could have medical applications.

Mechanical engineering major Hallie Zeller ’12took the course twice. “With an intimate class setting consisting of students from various departments of science and engineering, our discussions brought together many points of view,” she says. “I noticed that the lectures rarely fit the mold of just one particular field, and I’ve come to realize the importance of connecting bridges between disciplines.”

For Alec Eidelman ’13, a biochemistry major, the health and life sciences minor enabled him to expand his learning outside of his major. “Biochemistry will provide me with a strong foundation to succeed in a career, but the health and life sciences minor and my experience in the lab will bring my level of understanding up to a higher level,” he says.

Eidelman completed a 10-week independent research study this summer with Kurt. His project was related to Kurt’s research on the body’s immune response to cancer, specifically how to make the body recognize cancer cells better. The research is supported by a $190,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute.

The health and life sciences minor is part of the broader initiative in Lafayette’s strategic plan to “establish an integrated center for the life sciences equal in quality to the finest at any small college in the nation.” Initial planning for a life, earth, and environmental sciences facility calls for two phases: renovation of Kunkel Hall built in 1969 and an expansion that would incorporate computer science, geology, and environmental science.

“In the world today, biology is integrated with policies and economics,” says Roth, “and we have the opportunity to integrate it with engineering as well. “If we only renovate the biology facilities in Kunkel, we would be out of step with what is going on in the world. We want to create a physical structure that facilitates interaction, that brings together the types of expertise that are being brought to bear on issues of living systems today such as geology, environmental science, computer science, and bio-engineering. We want to take greater advantage of the science synergies that already exist on campus by creating new spaces that will enhance those interactions.”

Kurt encourages students to participate in laboratory research. “The final requirement for students enrolled in the minor is to take either a capstone course or to write an interdisciplinary honors thesis, bridging research from two different disciplines involving life sciences and health,” he explains.

Kurt is one of 60 faculty members from 15 different departments who are involved in interdisciplinary research and are willing to interact with other students and faculty associated with the minor. For example, students can pursue projects that bridge biology and psychology, neuroscience and engineering, or computer science and ethics. Research projects are initiated by the students. Kurt notes that their options are limitless.