Nov 7, 2013

Test Your Problem-Soving Quotient

In A Modeling-Based Approach to Biology, students are given open-ended problems that have no perfect answer. Think global climate change, antibiotic-resistant…

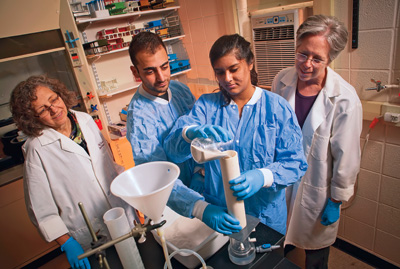

Robert Kurt, associate professor of biology (L-R), Tiffany Phuong ’16, Kofi Boateng ’16, and Chun Wai Liew, associate professor of computer science, studied the role of a protein in the growth of tumors.

by Lori H. Burke

“Students arrive with preconceived notions about what the field of biology is and how you study it. They see science as simply a checklist of things to memorize. But that’s not reality,” says Robert Kurt, professor and head of biology. “Unfortunately, though, that’s classically how it has been taught. And, students don’t learn well that way. They may get an A in the course, but they really haven’t learned to make the connections needed to be effective problem-solvers.”

A plan to dramatically change the paradigm of the collegiate biology experience began to unfold last year thanks to an $800,000 grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). The project includes creating student research experiences, boosting the diversity of students who study science, and supporting faculty and curriculum development.

Laurie Caslake (L-R), associate professor of biology, Michael Galperin ’16, Jasmeen Saini ’16, and Mary Roth, Long Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, investigated biofilms formed by bacteria in sandy soil.

Science Horizons was created to provide mentoring for 20 incoming students each year. They develop an understanding of research and delve into interdisciplinary problems in biology. They receive support to conduct research during January interim and can apply for an Interdisciplinary Research Fellowship in the summer. Guest lecturers such as Roger S. Newton ’72, Ph.D., FAHA, honors biology graduate, and founder, executive chairman, and chief scientific officer of Esperion Therapeutics Inc., and Fabiola Rivas ’97, honors biochemistry graduate, editor of Trends in Immunology, provide exposure to interdisciplinary careers.

The first five Interdisciplinary Research Fellows were chosen from among the Science Horizons group— Kofi Boateng ’16, Michael Galperin ’16, Camila Moscoso ’16, Tiffany Phuong ’16, and Jasmeen Saini ’16. They are energizing their learning as they put their preconceived ideas of science under the microscope. Guiding them are stellar professor-mentors, who are challenging and encouraging these pioneers to ask the tough questions about science and their futures.

Fellows conduct research through three summers. Following their first year, they apprentice with faculty from two disciplines. After sophomore year, they conduct research with a faculty member through the EXCEL Scholars program, and following junior year, they participate in the Lafayette Alumni Research Network program as LEARN Scholars. They also attend two scientific meetings.

“By graduation, our fellows will have done something that very few college students have done,” says Kurt. “Through these research experiences, they will become exceptional candidates for an honors thesis and well prepared for pursuing biomedical research and/or advanced degrees.”

As Saini, a biology major, looked forward to her college experience, she was uncertain about undergraduate research. “I had no idea how to go about it,” she says. “The thought of going to a professor to discuss it was really intimidating.” But knowing that she wanted to become a pediatrician made her determined. Her inspiration came from shadowing her aunt, Rumneet K. Saini ’92, a pediatrician in Catonsville, Md.

Saini and Galperin, a biology and French major, conducted research during January interim last year. They worked on a National Science Foundation-funded study conducted by honors student Tiffany Kimmel ’13 under the supervision of Laurie Caslake, associate professor of biology. The team investigated the effects of quorum-sensing inhibitors on biofilms formed by Pseudomonas fluorescens MIC102L in sandy soil.

The experience was empowering. “I am such a different person than when I first came to Lafayette. I feel myself growing and getting more confident every day.” This confidence will benefit Saini as she pursues her goal of becoming a pediatrician.

Last summer, Saini and Galperin continued their work with Caslake and Mary Roth, Simon Cameron Long Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and associate provost for academic operations.

Galperin credits his interest in science to his parents—his father, a physicist, and mother, a doctor, who emigrated from the former Soviet Union a few years before he was born. He is the brother of Diana ’08, a junior fellow at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and Ellen ’15, a computer science major.

“I have enjoyed all the problem-solving,” he says. “Professor Caslake pushed us out of our comfort zone to encourage us to investigate and really understand what we were doing.”

“I learned to think in a different way…analyzing information and asking more questions.”

—TIFFANY PHUONG ’16

The interdisciplinary aspects have deepened his interest in biology. “Health isn’t only related to biology. In fact, you can’t even approach a problem without seeing it from multiple perspectives,” he says. “Working in different scientific fields has opened my eyes to how broad the field of biology is, and why I love studying it.”

Galperin is weighing whether he will pursue a doctorate while earning his medical degree. He is considering someday working with an organization like Doctors Without Borders or Partners in Health and possibly long-term work in international affairs through the World Health Organization.

Boateng, a neuroscience major, moved to the Bronx from Ghana when he was just a few years old. “Growing up, I wanted to do something to help my family’s circumstances. I figured that medicine would be the best option for me to create change,” he says. “My goal is to return to Ghana and create an establishment—maybe a school or a hospital—that will help people.”

Last summer, Boateng and Phuong, a biology major, used computer modeling to study the role of MYD88 in tumor progression with the guidance of Kurt and Chun Wai Liew, associate professor of computer science and Peter C.S. d’Aubermont, M.D. ’73 Director of the Health and Life Sciences Program. Boateng sequenced MYD88, a protein known to contribute to tumor growth. He and Phuong used the computer program Netlogo to create the signaling pathway of toll-like receptors, components of a cell’s defense system.

“Science Horizons is a perfect opportunity to look at health from different perspectives and to do research that crosses different fields.”

—CAMILA MOSCOSO ’16

“Toll-like receptors play a critical role in innate immunity by detecting invading pathogens. If you have a mutated MYD88, that will dictate how well the cell can respond to pathogens,” says Boateng.

During their collaboration, Phuong used cutting-edge techniques to identify the presence of Myddosome complex in cells, which correlates with cancer progression. To conduct her research, Phuong taught herself co-immunoprecipitation, a protocol for studying protein-protein interactions. “Professor Kurt pushed me to be more independent,” she says. “He seemed confident in my abilities. Even if I did make mistakes, he always made it a learning experience.”

Phuong, who plans to pursue an M.D./Ph.D. program after graduation, says the experience taught her more than just new facts. “I learned to think in a different way. Professor Kurt and Professor Liew didn’t just want me to find information. They wanted me work with the information, analyze it, and ask more questions. You can’t just be a bystander or an observer in science.”

A new introductory course, A Modeling-Based Approach to Biology (see “Test Your Problem-Solving Quotient”), and a required capstone course focusing on interdisciplinary problem-solving have been added to the curriculum. And through faculty collaboration across the disciplines, half of the biology courses will be infused with interdisciplinary concepts and problem-solving.

Last summer, Megan Rothenberger ’02, assistant professor of biology, developed interdisciplinary modules for three courses in collaboration with William Bissell, associate professor of anthropology; David Brandes, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering; Michael Butler, assistant professor of biology; Benjamin Cohen, assistant professor of engineering studies; Tara Gilligan, visiting instructor of environmental studies/women’s and gender studies; Arthur Kney, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering; Kira Lawrence, associate professor of geology; and David Sunderlin, associate professor of geology.

Laurie Caslake (left) and Camila Moscoso ’16

Rothenberger says interdisciplinary instruction helps Lafayette model the type of real-world collaborations that are necessary to resolve this planet’s most challenging issues. “Students need to see that the world isn’t divided into departments, with biologists over here and historians over there,” she explains. “It’s important to be able to work together to develop solutions for the problems that we’re facing.”

In addition, the grant has enabled the department to add an interdisciplinary faculty member, Eric Ho, a computational biologist and assistant professor of biology with an affiliated appointment in computer science.

During January interim, Moscoso worked with Caslake on an area of the professor’s research that involves microorganisms found in the top layer of the desert, called the desert crust. The organisms undergo repeated drying and wetting through the year, and past research has shown that drying bacteria breaks their genome into small pieces, which they repair or prevent

from happening in the first place. Moscoso assisted Caslake in determining the level of natural resistance that some of these organisms have to bleomycin, an antibiotic that causes breaks in DNA.

Moscoso is considering options for her future. “Although I’m focused on medical school, being involved in Science Horizons is a perfect opportunity to look at health from different perspectives and to do research that crosses different fields.”

Already Moscoso has begun the process of paying forward this gift that has made such a difference in her life. “I want to be able to mentor other students to make the most of their experience at Lafayette,” she says. “It’s a big, positive cycle, and I want to encourage these new students who are coming in to try the experiences that have been so rewarding for me.”