A Great Serve

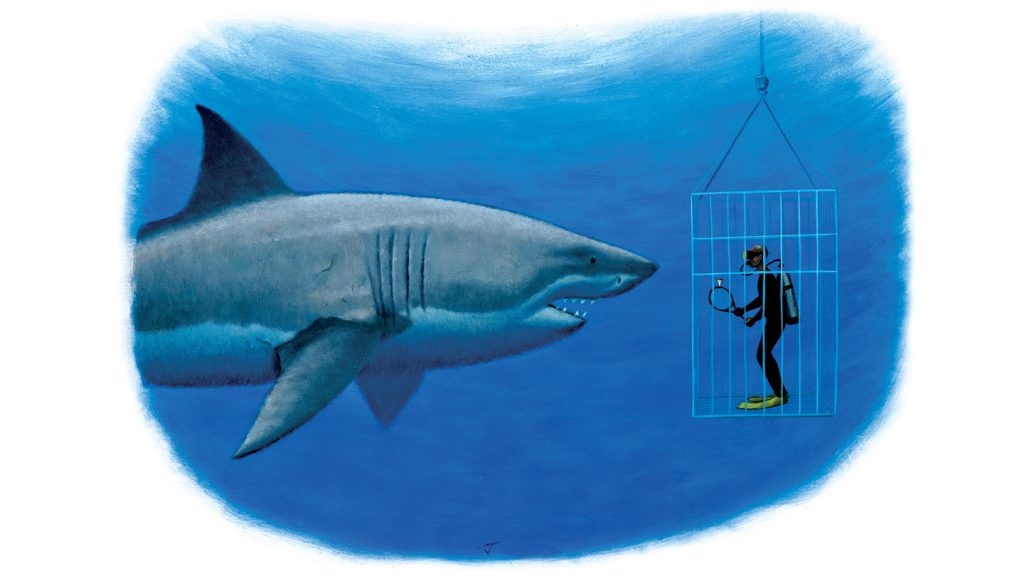

In the depths of the Atlantic Ocean, several miles off the coast of South Africa, a great white shark bolts out of the abyss and smacks his snout on a galvanized steel cage. His tail and dorsal fin slice through the water as he attacks the chum scattered around the cage.

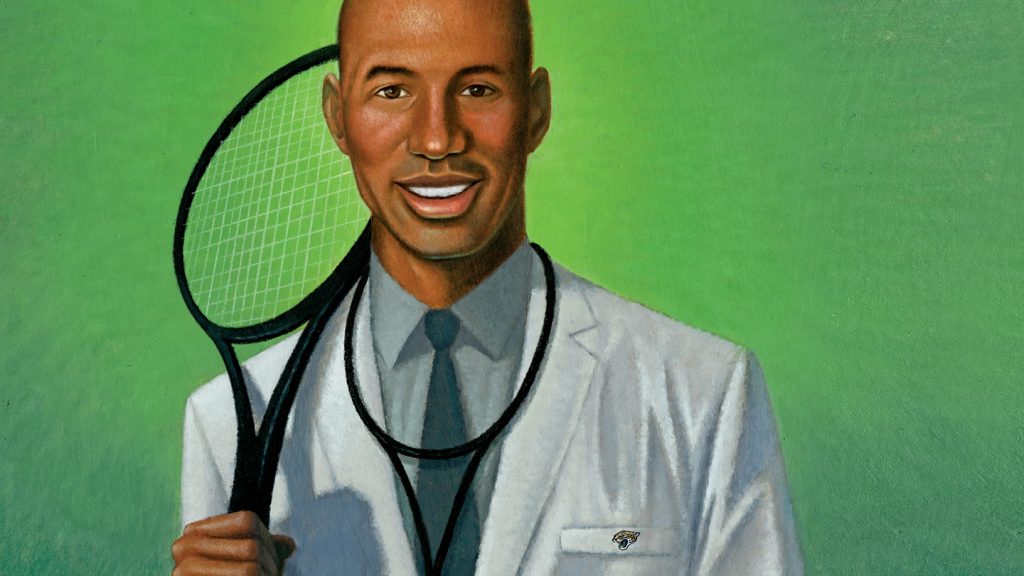

Inside that cage is Dr. David Doward ’91, a renowned spine and sports medicine physician, who at the time was one of the team doctors for the NFL’s Jacksonville Jaguars.

While the shark dive may seem like a life-altering experience, it was just one of several in 2010 when the physician took a hiatus from work and traveled the world.

While the shark dive may seem like a life-altering experience, it was just one of several in 2010 when the physician took a hiatus from work and traveled the world.

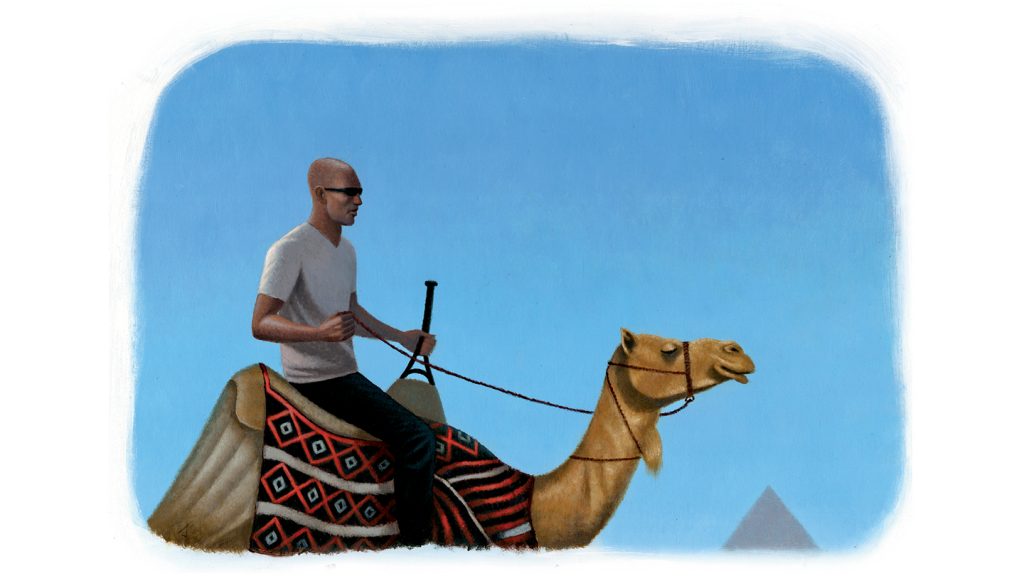

During his trek, he rode camels in Egypt, stayed in a castle in Scotland, traveled in armed vehicles in Israel, and yes, dove with sharks in South Africa. “As you can tell, I’m not your typical doctor,” Doward says. His patients aren’t typical either.

After a year of globetrotting, Doward left the Jaguars to become the “neutral” doctor for Davis Cup and Fed Cup, the men’s and women’s premier international tennis team competitions. Being the neutral doctor means that Doward’s responsibilities transcend geographic boundaries and country pride, making him a first responder when an athlete is injured to ensure impartiality on the court.

“This is a dream job,” Doward says from his home in Atlantic Beach, Fla. “I have such a passion for the sport. As a doctor, I do anything I can to facilitate keeping the athletes healthy.”

Few dream jobs come to pass without hard work, dedication, and sacrifice, the same attributes that propel amateur athletes into the professional ranks. For Doward, the path to the pros started 47 years ago in the U.S. Virgin Island of St. Croix.

Game On

Before he was David Doward, MD, internationally recognized and widely published interventional spine and sports medicine physician, there was David Doward, the all-star tennis player on his snail-shaped island in the Caribbean Sea.

Although St. Croix is only 84 square miles, it has produced its fair share of professional athletes, including former Major League Baseball player Jerry Browne, boxers Julius and John Jackson, Olympic sailor Peter Holmberg, and most famous of all, five-time NBA Champion Tim Duncan. (Duncan, as it happens, is Doward’s first cousin.)

Doward’s sport of choice was tennis, and he spent as many waking hours on the court honing his skills as he did anything else. He gained a reputation as a teenage phenom—he was sponsored by tennis racket manufacturer Prince Global Sports—and it wasn’t long before college recruiters began scouting his matches in the Virgin Islands.

One of them was Lafayette, and since Doward planned to major in engineering, it seemed like a good place to earn his varsity letter.

But after playing tennis for his first two years he decided to hang up his racket so he could focus more on his studies, he says. Graduating with a B.S. in chemical engineering and a minor in computer science, Doward decided he needed to decompress from the rigors of academia and headed to southern California to teach at a top junior tennis academy.

It was there he decided his calling was medicine, or more specifically the biomechanics of tennis and helping athletes prevent and recover from injuries. Sports medicine seemed the best way to incorporate both interests into a career. However, he hadn’t taken the necessary courses for medical school as an undergrad, so he applied for and was accepted to Columbia University’s Postbaccalaureate Premedical Program, which he completed in 1994. From there, he attended Cornell University’s medical school and received his white coat in 1999.

He was as sought after as a doctor as he was as a young tennis player. When he started looking for a job, a number of opportunities synergized with his concentration in sports medicine. There was the New York Knicks, which he worked with during his fellowship training; there was a faculty position at Stanford University, but he was turned off by the degree of politics in academic medicine; there were various college and professional teams in Los Angeles; and then there was a large orthopedic group that had a corner on the local professional, collegiate, and high school teams, including the Jaguars.

The irony was that Doward wasn’t a football fan. At least, not American football. He preferred soccer, and when he wasn’t studying or playing soccer, there was tennis.

“Football wasn’t for me at all back then,” he admits. “But there was an opportunity and I took advantage of it, and my skillset matched.”

He spent five years with the team, treating players during games for injuries ranging from concussions to contusions, to finger dislocations and shoulder separations. “We had it all,” he says.

Although he grew to love and appreciate football, he remained a tennis devotee. So when an opportunity presented itself to essentially conjure a job aligned with the Davis and Fed championships, he pounced.

Advantage Doward

In 2011 the Davis Cup was hosting a match in Jacksonville and needed a medical doctor on the court. Someone contacted Jacksonville Orthopedic Institute, the premier collection of orthopedists in the city, for which Doward is a partner. The other physicians did not hesitate to point to their on-site tennis aficionado.

“I had such a passion for the sport and for the Cup that every time there was a game they would contact me,” Doward says. He proposed being the Cup’s neutral doctor for all U.S. matches. It was no small undertaking for a managing partner of the 35-doctor, $54 million orthopedic group. However, the visibility of aligning Jacksonville Orthopedic Institute with the Davis and Fed cups was appealing to the other doctors, and there was no keeping Doward from his desire to remain associated with the sport.

When you merge things you have a passion for, like medicine and tennis, you can say you are truly doing your dream job.

The job is weighty. Like a doctor who oversees a prizefight, Doward is responsible for deciding whether a player’s injury on the court could become something worse. If so, he has the authority to stop play. Only once did he have to call a match.

It was 2013, and the U.S. was playing Sweden in the playoffs of the Fed Cup in DelRay Beach. The U.S. was winning 3-1 with one match left when Doward was summoned to the locker room.

Three of the four players on the squad were injured: Venus Williams was having trouble with her back, Serena Williams injured her right foot, and Sloane Stephens was complaining of a strained calf. After examining the athletes, Doward confirmed the injuries were legitimate and the team defaulted the last match.

“The U.S. had already won at that point so it was kind of moot,” he says.

Oftentimes, a super fan who lands a position with his favorite team has a hard time walking the line between doing his job and joining the party. Yet that is where Doward’s professionalism comes in.

“I would be invited to these cool parties, but I couldn’t really socialize,” he says. “I know my job, and I know what I’m supposed to do and what’s expected of me. As the ‘neutral’ doctor, even though I see the U.S. team all the time, I also see the Swedes and the Germans. I keep it professional. That’s how it has to be.”

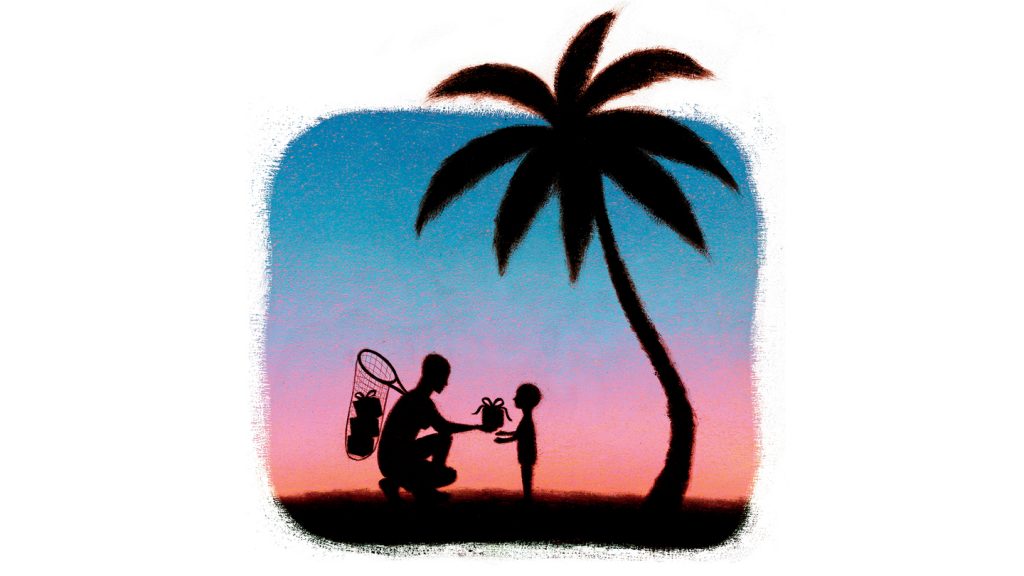

Something else that’s important to Doward is philanthropy. He’s made several medical mission trips to Jamaica. He joined a group that included general surgeons, obstetricians and gynecologists, pediatricians, and others to offer medical care to that island nation’s overwhelmed and understaffed medical community. Doward also volunteers with MaliVai Washington Youth Foundation in Jacksonville, where he works with and encourages inner-city adolescents to focus on their education. “I also explain to them that there is a pathway to becoming doctors.”

Game, Set, Match

Back in Jacksonville, Doward is no longer seeking thrills of the shark-diving sort. His next big adventure involves a trip down the aisle—he’s engaged to be married April 14, 2018—and then playing father to his future children.

“We plan on having a very large family,” he says. “I intend on spending as much time as I can enjoying every moment with them.”