Get Your App to School

A young man we’ll call Lewis was in danger of dropping out because he’d missed so many classes. The New York City alternative high school he was attending had mailed letters to his father. A machine had left voice messages on his home phone. No response.

Alexandra Meis ’08 with Augustus Grissett, attendance coordinator at Research and Service High School in New York City

Finally, the school tried a different approach and sent Lewis’ father a text message using an app designed by Alexandra Meis ’08, chief product officer of Kinvolved, a New York City-based software company she co-founded five years ago. Dubbed KiNVO, the app allows teachers to take attendance with a swipe of the finger and then automatically sends a text message to parents or guardians of K-12 students if their child is absent or late.

“The school was able to get in touch with the student’s father using the app, notifying him of his son’s absences,” says Meis. “The father was shocked and asked how he could help his son.”

An inconsistent presence in Lewis’ life for many months, the father arranged to meet the school’s administrator to discuss Lewis’ academic standing. The meeting between father and son was awkward at first, but with immense support from the school, they came to an understanding that it was essential for Lewis to graduate. “It was really the text message that the dad got from Kinvolved that brought them together again,” says Meis happily. “This work is hard, and I sometimes ask myself, why am I doing this? There’s bureaucracy, there’s politics, and all of these naysayers—people say no to the idea of digitizing communication between schools and families all of the time. But a story like this boy and his father, well, this is why I’m doing it.”

Chronic absenteeism is a pernicious problem—the most recent study estimates 6.8 million American students miss a month or more of school a year, with 50 percent of those cases occurring in districts with high poverty rates, according to Attendance Works, a national nonprofit devoted to creating awareness about the correlation between attendance and academic achievement.

The importance of consistent attendance starts in pre-K when behavior and learning habits are formed, says Meis. Research has shown that falling behind before third grade correlates not only with higher dropout rates but higher incarceration rates as well.

This is what led Meis and Miriam Altman, a former New York City high school history teacher, to launch Kinvolved in 2012, just over a year after they met as first-year grad students at New York University’s Robert F. Wagner School of Public Service. The app is now used in over 100 New York City Department of Education schools, with an expectation to double that number in the 2017-18 school year.

This is what led Meis and Miriam Altman, a former New York City high school history teacher, to launch Kinvolved in 2012, just over a year after they met as first-year grad students at New York University’s Robert F. Wagner School of Public Service. The app is now used in over 100 New York City Department of Education schools, with an expectation to double that number in the 2017-18 school year.

In addition, the company is rapidly expanding nationwide and works with school districts in cities like North Brunswick, N.J., and Atlanta, Ga.

Last year, Kinvolved sent more than 4 million text messages in over 55 languages.

A for-profit company, Kinvolved charges a per-student licensing fee per annual contract for all teachers and administrators in a school to use the program and have classwide or schoolwide analytic capabilities, plus IT support and Community and Culture Coaching, Kinvolved’s in-person professional development. “We looked at tools in the marketplace, and there wasn’t something that was narrowly focused on getting kids in schools,” says Meis. “If we can connect with the family right away about attendance, that opens up other things we can talk about. But we need to do that in a proactive and positive way. We’re seeing that change happen via the power of a simple text message.”

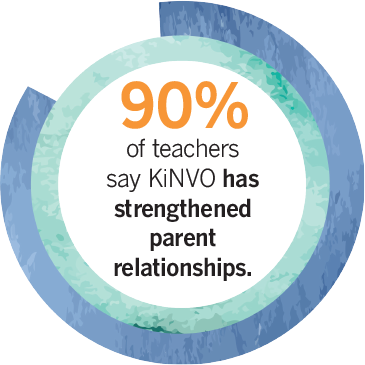

Her goal of elevating student attendance seems to be working. Kinvolved partner schools improved attendance 13 times more than other schools, according to Meis.

A New York City Department of Education “renewal school,” John Adams High School in Queens is required to show a marked change in attendance and academics. So it brought in KiNVO to tackle truancy.

“It paid off,” says Altman. “This school started to see progress, including a 12 percent increase in ninth-grade student attendance and a 4 percent schoolwide increase in average daily attendance almost immediately.”

But it’s the personal testimonies that are most impactful—and likely one of many reasons why the pair was named to Forbes’ list of “30 Under 30” in education in 2015.

Banj August, a theater teacher and data specialist at Manhattan’s Urban Assembly Maker Academy, uses KiNVO in his own classroom and sees “immediate benefits.”

“Students are quick to learn which teachers won’t let them get away with being late, and teachers keep in regular contact with families,” says August. “That kind of shift has an incredible transformative potential in a classroom.”

Runi Pswarayi, Kinvolved’s creative director, met a young woman whose spotty attendance rate was jeopardizing her chances of graduating. “When the school began texting her mother about her absenteeism, her mother began waking her up at

4 a.m. so that she could get to school on time,” says Pswarayi. “She went from not believing she could graduate to having 100 percent attendance. She now has offer letters from five colleges.”

A Desire to Help

A soft-spoken woman at the age of 31, Meis calls herself an introvert, but with that slight shyness comes an assured assertiveness and a no-nonsense demeanor. She’s powerfully articulate and passionate when discussing Kinvolved and the blight of attendance attrition. But like many post-collegiate explorers, she arrived at her vocation in a roundabout way, never envisioning herself as a future software entrepreneur while at Lafayette.

Graduating as a psychology major with a minor in anthropology and sociology, Meis always wanted to help others through public service. While an undergraduate, she volunteered at Easton’s Third Street Alliance, a women’s and children’s shelter, where she was deeply moved by the daily struggles

of single mothers.

Inspired by her volunteer work in the Lehigh Valley, she joined AmeriCorps and moved to New York, eventually working in the pediatrics department at Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center. Once her 12-month AmeriCorps tenure ended, she stayed at the hospital for several more years as a special projects coordinator at Bronx-Lebanon’s Autism Treatment and Advocacy Center.

She found that parents wanted to help their children, but they didn’t know how to navigate the system for special needs services their children were entitled to from the government. “We started a parents’ support group to go beyond the medical diagnoses, to enable moms to connect with other moms and learn how to advocate for a child with autism in the public education system,” she says.

Alexandra Meis ’08 and company co-founder Miriam Altman at Kinvolved Summer Summit 2017

While there, Meis observed hundreds of families, especially those headed by single mothers, facing impassable barriers as they struggled to become more involved with their children’s education.

“Our moms were working three jobs, and English wasn’t their first language,” Meis recalls. “There was poverty…and with that comes violence, substance abuse, and health issues.”

Growing up in Chestnut Hill, Pa., the only child of a podiatrist and a general vascular surgeon, Meis did consider medical school. She took night classes with a pre-med angle at Columbia University while working at Bronx-Lebanon, but that route didn’t feel right. By her mid-20s, Meis reached what she calls “a tipping point.”

“I saw so much trial and tribulation with these families [at Bronx-Lebanon], and there was only so much I could do without a professional degree,” says Meis. She enrolled at NYU’s Wagner School of Public Service in 2011 to pursue a master’s degree in health policy and analysis.

There she met Altman, who taught in Manhattan with Teach For America for several years. Altman became aware of how attendance affects academic success when she discovered that all of her students but one who failed the State Regents exam were absent at least one day a week.

Meis and Altman’s parallel formative experiences led to frequent conversations about poor attendance and the attrition rate in schools—and the seed of Kinvolved was planted. But neither woman was technically adept to build the app, so seeking an outside developer was key.

“We’ll Help You Build Your App!”

In winter 2012, they entered a BeMyApp Global Mobile App Competition “hackathon” at City University of New York to see if they could coax a software team onboard.

“We had about 60 seconds to present our idea, the solution, and see if anyone was interested in building a prototype,” says Meis, who explained their idea to the room of tech-heads and designers. “Everything else presented was a dating or food-delivery app. We left thinking no one is going to want to build it. [Kinvolved] is not sexy or cool. But then I turned around and saw that people were raising their hands, saying, ‘We’ll help you build your app!’”

They won that BeMyApp event and, using the prototype designed by developers they met at the hackathon, entered the inaugural 2012 National Public Policy Challenge, a student competition at Fels Institute of Government at University of Pennsylvania.

They won that BeMyApp event and, using the prototype designed by developers they met at the hackathon, entered the inaugural 2012 National Public Policy Challenge, a student competition at Fels Institute of Government at University of Pennsylvania.

Once again, the women earned top prize—$15,000, which they invested in research and building the app itself. Eventually, they tested a beta version at two schools: West Harlem’s P.S. 125 and Ralph Bunche School, which saw a 5 percent increase in attendance and remains a client five years later.

Kinvolved’s office in New York’s Financial District is catty-corner from Kristen Visbal’s hands-on-hips Fearless Girl bronze sculpture, installed in 2017, that stares down Arturo Di Modica’s Charging Bull statue, a symbol of Wall Street since 1989. A not dissimilar scene was played out as Meis and Altman sought additional funding from male venture capitalists. Meis says that as a team, she and Altman have always been “fearless” when it comes to Kinvolved, akin to racehorses with blinders, galloping toward a finish line. But when the time came to raise capital from investors, they became aware of a different lexicon used to frame their aspirations. While male peers were praised as “having a venture” with a potential “empire,” Meis and Altman were deemed as “cute” with a “cool project.”

“We ignored it,” says Meis brusquely. “I don’t want to be spoken to as a female founder. I want to be spoken to because I’m a founder.”

Serious Challenges

Five years since their idea became reality, Kinvolved employs a full-time staff of 10 and two part-timers. In the 2016-17 school year, Kinvolved experienced 132 percent sales revenue growth, the company’s highest rate since its establishment.

But there are serious challenges ahead for the 2017-18 school year. Meis has heard from school principals that some students now fear attending school due to the elimination of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals as well as U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement roundups of undocumented families.

“I hope that our software is used to still engage those families via text message if parents are afraid of coming into the school building,” says Meis. “It’s years and years of exclusion that we’re up against, and how do you change that via text message? You don’t. But at least Kinvolved is a way to broker that relationship.”

Nonetheless, she’s quick to point out that neither she nor Altman are living in an idealized Kinvolved bubble.

“We’re not looking at things through rose-colored glasses, believing that all kids will come to school if their parents get text messages,” says Meis. “Our goal is to not just offer software but to cultivate a movement to improve and elevate student outcomes. And change takes time.”