Coming Out

Just before he was about to graduate, Riley Temple ’71 learned he was a candidate for the George Wharton Pepper Prize, bestowed annually on the senior who most closely represents the Lafayette ideal. A member of Student Government, former president of the predominantly Jewish fraternity Pi Lambda Phi, and a member of Association of Black Collegians, as well as other campus groups, Temple was a worthy choice.

Only he didn’t agree. So he asked the dean of students to remove his name from the ballot.

“This whole notion of a Lafayette ideal was not something to which I aspired,” he says, “nor was it, I believed, conceived to include someone like me.”

Someone who is gay.

Temple told very few people what he had done. He kept it to himself for decades. But now, thanks to a new oral history project he helped inspire, his experience has been recorded for posterity. Called the Queer Archives/LGBTQ Oral History Project, it aims to capture and preserve experiences and reflections of Lafayette’s LGBTQ alumni, faculty, and staff over the decades. The interviews will ultimately live online, linked to a digital platform that will connect them to related materials from the Skillman Library College Archives, such as LGBTQ posters, T-shirts, and photos.

Temple told very few people what he had done. He kept it to himself for decades. But now, thanks to a new oral history project he helped inspire, his experience has been recorded for posterity. Called the Queer Archives/LGBTQ Oral History Project, it aims to capture and preserve experiences and reflections of Lafayette’s LGBTQ alumni, faculty, and staff over the decades. The interviews will ultimately live online, linked to a digital platform that will connect them to related materials from the Skillman Library College Archives, such as LGBTQ posters, T-shirts, and photos.

So far, 19 alumni, faculty, and staff have shared tales of loneliness, courage, fear, and occasional triumph as members of a college that was ranked the most “Homophobic” in the nation in 1992 and a place where “Gay Students Are Ostracized” in 1993 by Princeton Review. Their stories trace the evolution of campus culture from the days when no one dared peek from the closet door to 2016 when an openly gay international student won the Pepper Prize.

The project comes at a seminal time. As colleges recognize the needs and contributions of their LGBTQ communities and students are demanding expansion of visibility and services, documenting past policies and LGBTQ history is a necessary component for driving change.

“If we get this right, it will last,” says Mary Armstrong, who conducted the interviews as Charles Dana Professor and chair of women’s and gender studies. “It could help transform the institution and the current student experience. And it will honor the courage and grit of alums from the past. And I think it will have real intellectual and political impact on campus.”

Hurdles Remain

Lafayette offers LGBTQ student groups Quest and Behind Closed Doors, a Gender and Sexuality Resource Center, Safe Zone education training on LGBTQ issues for students, faculty, and staff, an annual LGBTQ leadership conference, and a new coordinator of gender and sexuality programs. Gender-neutral bathrooms and housing have been installed, and most recently, the College instituted a policy allowing students to specify a preferred first name and pronouns.

Lafayette offers LGBTQ student groups Quest and Behind Closed Doors, a Gender and Sexuality Resource Center, Safe Zone education training on LGBTQ issues for students, faculty, and staff, an annual LGBTQ leadership conference, and a new coordinator of gender and sexuality programs. Gender-neutral bathrooms and housing have been installed, and most recently, the College instituted a policy allowing students to specify a preferred first name and pronouns.

The Quest board with faculty adviser Mary Armstrong, Dana Professor of Women’s & Gender Studies and English, during a Queer Archives event. Back row, L-R: Jennifer Wellnitz ’19, Megan Mauriello ’19, Armstrong, Jamie Taber ’19, Paige Fenn ’19. Front row, L-R: Esra Demirhan ’18, Sarah Mudrick ’18.

None of that was around when Stephen Parahus, a participant in the Queer Archives Project (QAP), graduated in 1984.

“There was no LGBTQ culture then,” says Parahus, senior director of health and benefits at Willis Towers Watson in New York City. “I was not out, and it would never have dawned on me to come out.”

There was no upside. He had come from a predominantly white straight enclave in northern New Jersey and viewed Lafayette as his ticket for inventing who he would be as a successful adult. The last thing he wanted to do, he says, was become socially ostracized. “So you take anything that’s not going to serve your cause and bury it at the door.”

That was the prevailing philosophy of many project participants who graduated in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s—stay quiet and don’t make waves. And by the mid-1980s, the AIDS epidemic and anti-gay sentiment were sweeping the United States.

It “would’ve been unthinkable and unsafe” to come out, says Harlan Levinson ’83, a financial adviser at Morgan Stanley.

Dr. Catherine Hanlon ’79 was threatened with expulsion when parents of someone she had briefly dated her sophomore year called the school to complain about Hanlon’s relationship with their daughter. The student’s parents withdrew her from the College. Hanlon learned of the complaint after being summoned by the dean to his office the first week of junior year.

“He talked about having me removed from school,” says Hanlon, an emergency room physician and professor of medicine.

She was on the dean’s list and a decorated varsity athlete who played three sports. This couldn’t be happening. “If I lose everything then I’ll having nothing left to lose,” she recalls telling him. “I’ll go to the press … I’ll go to whoever I have to go to and talk about how I was treated here.”

She was on the dean’s list and a decorated varsity athlete who played three sports. This couldn’t be happening. “If I lose everything then I’ll having nothing left to lose,” she recalls telling him. “I’ll go to the press … I’ll go to whoever I have to go to and talk about how I was treated here.”

The experience “blasted her out of the water,” she says, and she remained closeted and isolated at Lafayette. It wasn’t until she moved to Philadelphia for medical school on an Air Force scholarship that she began coming to terms with her orientation. She has since reconnected to the College as a member of the Maroon Club and last year was responsible for bringing celebrated LGBTQ activist and author Rita Mae Brown to campus.

A Defining Moment

In 1992, a portion of the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt found its way to Lafayette. Conceived in San Francisco as a memorial for those who had died of AIDS, the 54-ton quilt now contains more than 48,000 panels.

Lisa LeMoult ’92 led the Lafayette organizing committee in signing the College’s panel of the AIDS Quilt. L-R: Bobbi Kerridge, assistant director of student activities; Meredith Renk ’92; Dave Unanue ’92, committee co-chair; Gregg Betheil ’92; LeMoult; Megan O’Connor ’92; Deb Hoff, assistant director of student residence and committee co-chair, Kara McCarthy ’92.

Temple, an attorney in Washington, D.C., who had been recognized with a Point of Light award from President George H.W. Bush for his work on HIV/AIDS awareness, gave the keynote address during the quilt’s unfurling in Kirby Field House.

“It was a very big crowd, a very solemn crowd,” says Temple, who soon after was named to Lafayette’s Board of Trustees, its first openly gay member. “I think it was a major turning point for the College.”

Ann Carter, who after 34 years with the College retired in 2015 as director of development communications, says she was surprised by the impact the quilt had on the campus community. “It was enormous,” she says. “It’s hard to describe.”

A member of the organizing committee, Carter recalls watching the change in students as they viewed the quilt.

“Guys from a fraternity, a class, a sports team would come, and you could see them arriving, ‘Oh, let’s get this over with,’” says Carter, who had seen the quilt in Washington, D.C., with her partner, Carolynn Van Dyke, now Francis A. March Professor Emerita of English. But students soon grew somber viewing the panels, often peeling away from the group to walk the perimeter of the quilt alone. “It became a very introspective, private” experience, she says.

It was the start of a shift, and people began feeling more comfortable talking about what it means to be gay at Lafayette, she says. Soon after, the term “sexual orientation” was introduced as a nondiscrimination clause in the College catalog.

Gay? Fine by Me

But for many students questioning their orientation, Lafayette remained a lonely place.

When Dan Reynolds ’08 arrived in 2004, he had come out senior year in high school and didn’t want to have to conceal his true self at Lafayette.

When Dan Reynolds ’08 arrived in 2004, he had come out senior year in high school and didn’t want to have to conceal his true self at Lafayette.

“I wanted to be out from the beginning,” he says. “That was important to me, but I think I scared a lot of people. I was visually queer. I would wear makeup and shirts so you could see my abdomen.”

It came with consequences. He found it extremely hard to make friends. Someone wrote “fag” on his door. When his roommate found out he was gay, he stopped talking to him and then left second semester without a word.

“I definitely felt like there was a wall between me and the rest of the student body,” he says.

He thought about transferring, but when Quest, Lafayette’s LGBTQ and ally student organization, nearly folded because no one volunteered to be president, Reynolds stepped up. The position, which he held for the next two years, also gave him a platform and resources to affect positive change.

“The school wasn’t as bad as people thought it was,” he says. “I wanted to show that there were a lot of people accepting queer people, and there were a lot of queer people on campus already.”

In one of his first acts as president, he decided to hold a drag ball. A friend of his had organized one at another institution, and Reynolds thought it would be a fun way to introduce a queer party into the social scene.

“But we were terrified to throw it,” he says. “We hired a security person to patrol it.”

It went so well that it became an annual event for Quest, and by Reynolds’ senior year, Greek Life was a co-sponsor. “It showed it wasn’t just a party for gay people,” he says. “It was something everyone could participate in.”

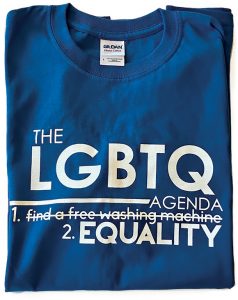

Then in 2006, Reynolds decided to bring the Gay? Fine by Me campaign to Lafayette. The T-shirt project had started at Duke University in 2004 after Princeton Review named the campus Most Gay Unfriendly in America. Reynolds thought it was a great way to test whether the LGBTQ community at Lafayette had allies, straight students supportive of gay peers.

There was just one problem. Quest didn’t have a budget to buy T-shirts with the Gay? Fine by Me slogan, so it had to go before student government and ask for a donation.

“There was a moment of quiet, and then one of the student reps said, ‘I think I speak for everyone in saying that this is something we all want to do,’” Reynolds recalls.

Top: Kristen Berger ’15, Paul McLoughlin, Ann Carter, Bryan Fox ’10.

Bottom: Catherine Hanlon ’79, Phil James ’82, Matt Pagano ’09, and Carolynn Van Dyke.

Quest members then held a weeklong campaign in Farinon. Students who signed up for a T-shirt also signed pledges to be allies of the gay community. So many students requested T-shirts that Reynolds had to make an emergency appeal before student government for more funds.

On the day of the rally, more than 300 students in multi-hued T-shirts ringed the Quad. It was a display of support and acceptance Reynolds says he had never seen before but always suspected was there. “Lafayette came out to me at that moment.”

The rally made local television news but didn’t garner coverage from The Lafayette student newspaper, an omission the editor explained by saying the staff was at a student journalism conference and no one was around to cover it, says Reynolds. The explanation didn’t lessen the disappointment.

“We wanted to preserve this in the record and let other alumni know that this thing that had seemed so impossible had taken place,” he says.

So the group took matters into its own hands. Reynolds crafted an article, printed hundreds of copies on bright green paper, and Quest members including Jess Elliott ’09, Danielle Bero ’07, Jennifer Aranda Troup ’07, and Charles Felix ’08 inserted them into every issue of The Lafayette under the thin light of dawn. The editor was furious, Reynolds says, and filed a complaint with the director of student life. A hearing was held. The editor argued it was the paper’s job to determine content, Reynolds says, and Quest had set a dangerous precedent.

But not representing the interests of all groups was worse, Reynolds testified.

“It is so difficult for people who are marginalized to have a voice in this community,” he recalls saying. “We broke your rules, but we did this because we wanted to be represented.”

The experience led Reynolds to pursue a career in journalism, and he is now senior editor of social media at The Advocate, the oldest and largest LGBT-based publication in the United States.

Opening Doors

The rally gave the LGBTQ movement visibility, but Lafayette still lagged behind its peers in regard to institutional resources.

Top: Stephen Parahus ’84, Leah Wasacz ’16, Dan Reynolds ’08, Harlan Levinson ’83.

Bottom: Tom Gibbons ’87, Julia Guarch ’15, Willow Wheelock ’15, and Jeffrey E. Finegan Jr. ’17.

Armstrong recounts coming to campus in 2009 to interview for the women’s and gender studies position she now holds and asking to meet with directors of the LGBTQ and women’s centers.

“Everybody looked very nervous and that’s when I realized those things didn’t even exist here,” she says.

She still took the job and has been instrumental in crafting courses such as Sexuality Studies, Lafayette’s first LGBTQ studies course, and other initiatives designed to introduce queer studies into the Lafayette academic experience.

The campus continued to make strides, and in 2012 two openly gay administrators arrived on campus—

Paul McLoughlin as dean of students and Gene Kelly, the College’s first coordinator of gender and sexuality programs.

“The movement around us was changing,” says McLoughlin, who is now vice president and dean of the college at Colgate. “Lafayette was making progress on gender-neutral housing and bathrooms,” important steps toward accommodating transgender students.

But there was still work to be done. McLoughlin says he found that Lafayette wanted to be “open” and “affirming” toward the LGBTQ community, but there were things “that didn’t match that.” For example, during his final interview for the dean of students position, the College flew his husband to campus. However, when he landed the job, health care and beneficiary forms didn’t give him the option of naming a same-sex partner.

This hit a nerve with McLoughlin, who legally married his husband in 2004 in Massachusetts. He brought the issue to the attention of human resources, and the language was quickly changed online, and a year later it showed up in print materials. The College has since replaced “wife” and “husband” on beneficiary forms with the gender-neutral term “spouse.”

As the climate was opening up on campus, alumni began organizing, and the first LGBTQ Homecoming reception was held in 2013. Only about 20 people showed up, but it felt like a good moment, says McLoughlin. “We were signaling to alum that they existed, whether they had been out or not at Lafayette.”

Behind Closed Doors

The decision to come out at Lafayette has always been a tricky one for many students. The culture can be homophobic but is more commonly heteronormative, a difficult landscape to navigate when questioning sexual orientation. As a result, some students stay closeted, preferring to hide their identity than risk being shunned or gossiped about by their peers.

That’s what happened to Stacey-Ann Pearson ’15, who arrived on campus from Jamaica, where she grew up in a conservative Christian household and was unable to explore her identity. She was excited to come to Lafayette and the United States in particular, where she had heard it was “all rainbows and sunshine for queer people all the time.”

Then she attended First-Year Orientation and overheard another student making negative comments about lesbians.

“It sent me right back to a place of ‘Oh my gosh, this is just like home,’” says Pearson. “‘I guess I’m not coming out.’”

It wasn’t until she went abroad to New Zealand her sophomore year and met students from other colleges who were comfortable with being gay, bisexual, and transgender that she decided to “live her truth.”

“That’s when I realized, you know what? I don’t care anymore,” she says. “I’m going to be out.”

But when she returned to campus in the fall, she discovered there wasn’t a support system for the closeted community. Quest was a great resource for students who were out, but nothing existed for those conflicted about their orientation or afraid to announce it. She then approached Kelly and with his help and that of friend Kristen Berger ’15 founded Behind Closed Doors (BCD), a private environment for students to discuss issues of gender and sexuality.

But when she returned to campus in the fall, she discovered there wasn’t a support system for the closeted community. Quest was a great resource for students who were out, but nothing existed for those conflicted about their orientation or afraid to announce it. She then approached Kelly and with his help and that of friend Kristen Berger ’15 founded Behind Closed Doors (BCD), a private environment for students to discuss issues of gender and sexuality.

“You need a space to think about things” and consider whether something is even a possibility, she says. “Sometimes you can’t get to that place on your own.”

A nominee for the Pepper Prize her senior year and the College’s first recipient of a prestigious Schwarzman Scholarship, Pearson now works as an international strategy consultant in Beijing, where she earned a master’s degree in international relations and affairs from Tsinghua University.

The formation of BCD was not only a milestone in the history of Lafayette’s LGBTQ community, it has created a vitally important haven for transgender students.

“That place was … everything I needed,” says Leah Wasacz ’16, who attended her first BCD meeting December of her junior year as she was transitioning from male to female. Wasacz says she was struck by the diversity of the group. “Stacey (Pearson) is Jamaican, and we had international students there, and gay men, and lesbians, and I was a trans person,” says Wasacz, now a math tutor. “It was a microcosm of what Lafayette talks about when they talk about diversity.”

If we get this right, it will last. It could help transform the institution and the current student experience. And it will honor the courage and grit of alums of the past. –Mary Armstrong

Wasacz wasn’t the first student to identify as transgender. In 2007, Ashley Fox changed his name to Bryan Fox ’10 and transitioned while on campus. He notes some people rallied around him while others made nasty comments. “It was a mixture,” says Fox, a youth counselor at Ali Forney Center for homeless LGBT youth in New York City.

Jeff Finegan ’17, one of the most recent grads to record his story for the Queer Archives, transferred to Lafayette in 2014 knowing in his “heart of hearts” he would never be able to come out at the Patriot League institution he had attended for a year. He recalls a meeting with McLoughlin.

“He said he had been with his husband for a number of years, and I thought, ‘OK, I can do this,’” says Finegan, legislative correspondent in the Washington, D.C., office of Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah). “I didn’t want to come here and trick people.”

Finegan says his experience at Lafayette as an openly gay student was positive as he felt “supported and encouraged” by his professors and peers. It also helped, he says, that his muscular build of 6 feet, 3 inches doesn’t conform to the gay stereotype.

Finegan says his experience at Lafayette as an openly gay student was positive as he felt “supported and encouraged” by his professors and peers. It also helped, he says, that his muscular build of 6 feet, 3 inches doesn’t conform to the gay stereotype.

“On a campus with a large athletic presence, it can sometimes be challenging to be seen as a token of the gay community,” he says, although he was identified by most students as the guy who always had something to say in class.

“I had factors more identifiable than my sexuality,” he says. As such, he “was able to be an ambassador for the community.”

Nonetheless, there’s a difference between a culture of tolerance and a thriving LGBTQ community with a social scene.

“Researchers will tell you that 8 to 12 percent of the population is not heterosexual,” Finegan says. “If you apply that math to Lafayette, roughly 300 individuals on campus are not heterosexual. I’m not advocating for students to proclaim their orientation if they’re not ready, but is there something an institution can do to create conditions that are friendly for coming out?”

It’s an important question, Armstrong says, as it strikes at the heart of Lafayette’s ethos—enabling all students to live and thrive in an increasingly interconnected world.