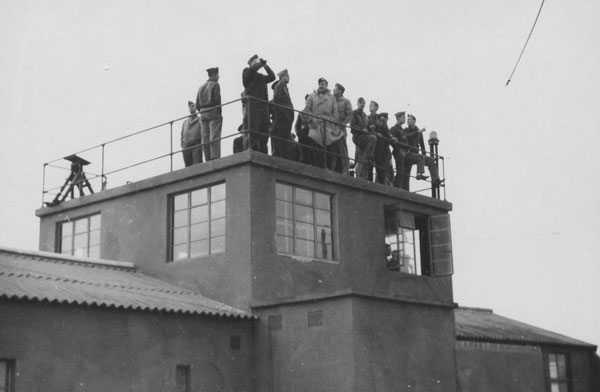

PHOTOGRAPH BY HUNDREDTH BOMB GROUP ARCHIVES (HISTORIAN, MICHAEL FALEY)

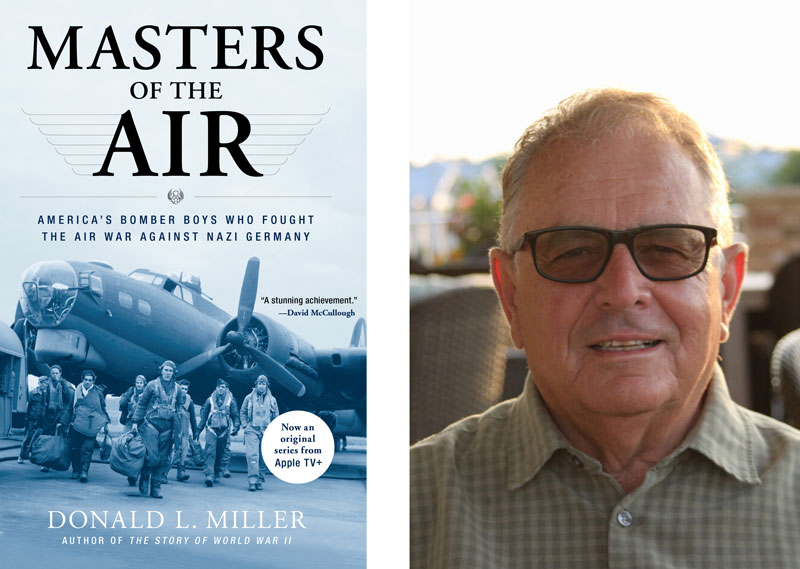

Masters of the Air

The book by award-winning author and historian Donald L. Miller, John Henry MacCracken Professor Emeritus of History, inspired the highly anticipated World War II miniseries.

Before its remarkable global premiere on Apple TV+ in January, Masters of the Air, adapted from Miller’s book Masters of the Air: America’s Bomber Boys Who Fought the Air War Against Nazi Germany, had been developed for more than a decade by executive producers Steven Spielberg, Tom Hanks, and Gary Goetzman—the same creatives behind the acclaimed World War II war dramas Band of Brothers and The Pacific. (It was worth the wait, as the show’s debut was the most-watched series launch in Apple TV+ history.) Masters of the Air follows the lead of big-budget productions: high-tech visual effects, star-studded performances, and elaborate sets.

Miller’s book, which was published by Simon & Schuster in 2007, shares the stories of individuals who courageously left U.S. soil to fight, and fly, in formation at 25,000 feet in the sky. In the early 2000s, Miller turned to Lafayette EXCEL Scholars like Katherine Blair Mulready ’04 and Lauren Sheldon ’04 to identify these veterans and document their firsthand accounts. More recently, EXCEL Scholars Matthew Ryan ’18, Emily Koenig ’18, and James Onorevole ’17 worked with Miller on the Apple TV+ adaptation by pitching storylines, locations, and resources for television. For Onorevole, who studied history and civil engineering at Lafayette, the experience inspired and redefined his outlook on research. “Dr. Miller imbues his retelling of history with narratives centered around people because nothing is more relatable and engaging than the human experience,” he says.

In the following excerpt from the prologue, “The Bloody Hundredth,” Miller (pictured, above) introduces several American wartime heroes from the 100th Bomb Group, including Maj. Gale “Buck” Cleven, Maj. John “Bucky” Egan, and Lt. Col. Harry Crosby while detailing the emotional and—for far too many—fateful toll of serving in the Eighth Air Force’s efforts during World War II.

Until Allied armies entered Germany in the final months of the war, strategic bombing would be the only battle fought inside the Nazi homeland.

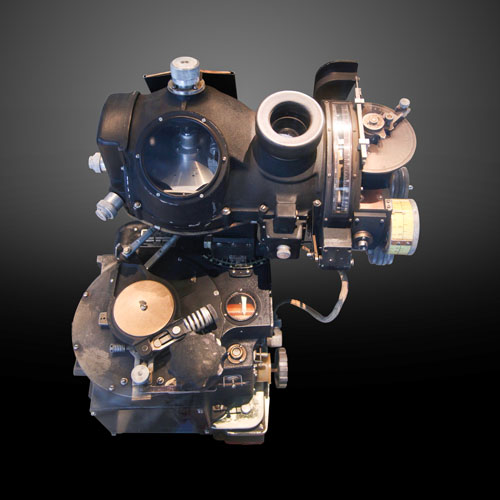

The Eighth Air Force had been sent to England to join this ever accelerating bombing campaign, which would be the longest battle of World War II. It had begun combat operations in August 1942, in support of the British effort but with a different plan and purpose. The key to it was the top secret Norden bombsight, developed by Navy scientists in the early 1930s. Pilots like Johnny Egan had tested it in the high, sparkling skies of the American West and put their bombs on sand targets with spectacular accuracy, some bombardiers claiming they could place a single bomb in a pickle barrel from 20,000 feet. The Norden bombsight would make high-altitude bombing both more effective and more humane, Air Force leaders insisted. Cities could now be hit with surgical precision, their munitions mills destroyed with minimal damage to civilian lives and property.

The Eighth Air Force was the proving instrument of “pickle-barrel” bombing. With death-dealing machines like the Flying Fortress and the equally formidable Consolidated B-24 Liberator, the war could be won, the theorists of bomber warfare argued, without a World War I-style massacre on the ground or great loss of life in the air. This untested idea appealed to an American public that was wary of long wars, but less aware that combat always confounds theory.

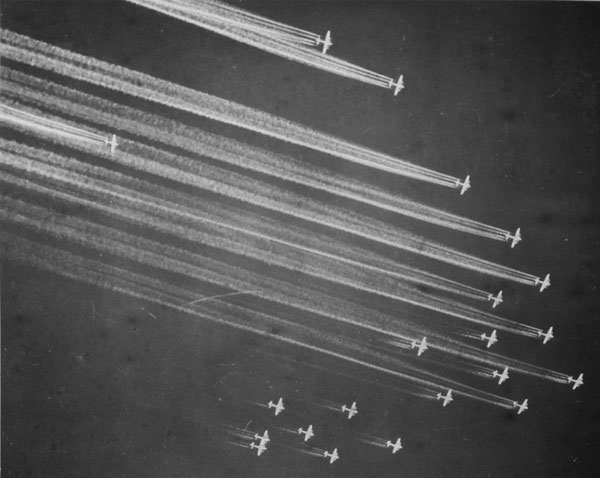

Daylight strategic bombing could be done by bombers alone, without fighter planes to shield them. This was the unshakable conviction of Brig. Gen. Ira C. Eaker, the former fighter pilot that Carl Spaatz had picked to head the Eighth Air Force’s bomber operations. Flying in tight formations—forming self-defending “combat boxes”—the bombers, Eaker believed, would have the massed firepower to muscle their way to the target.

Johnny Egan believed in strategic bombing, but he didn’t believe this. He had entered the air war when Ira Eaker began sending his bomber fleets deep into Germany, without fighter escorts, for at that time no single engine plane had the range to accompany the heavies all the way to these distant targets and back. In the summer of 1943, Johnny Egan lost a lot of friends to the Luftwaffe.

There were ten men in the crew of an Eighth Air Force heavy bomber. The pilot and his co-pilot sat in the cockpit, side by side; the navigator and bombardier were just below, in the plane’s transparent Plexiglas nose; and directly behind the pilot was the flight engineer, who doubled as the top turret gunner. Further back in the plane, in a separate compartment, was the radio operator, who manned a top-side machine gun; and at mid-ship there were two waist gunners and a ball turret gunner, who sat in a revolving Plexiglas bubble that hung—fearfully vulnerable—from the underside of the fuselage. In an isolated compartment in the back of the plane was the tail gunner, perched on an oversized bicycle seat. Every position in the plane was vulnerable; there were no foxholes in the sky. Along with German and American submarine crews and the Luftwaffe pilots they met in combat, American and British bomber boys had the most dangerous job in the war. In October 1943, fewer than one out of four Eighth Air Force crew members could expect to complete his tour of duty: twenty-five combat missions. The statistics were discomforting. Two-thirds of the men could expect to die in combat or be captured by the enemy. And 17 percent would either be wounded seriously, suffer a disabling mental breakdown, or die in a violent air accident over English soil. Only 14 percent of fliers assigned to Major Egan’s Bomb Group when it arrived in England in May 1943 made it to their twenty-fifth mission. By the end of the war, the Eighth Air Force would have more fatal casualties—26,000—than the entire United States Marine Corps. Seventy-seven percent of the Americans who flew against the Reich before D-Day would wind up as casualties.

As commander of the Hundredth’s 418th Squadron, Johnny Egan flew with his men on all the tough missions. When his boys went into danger, he wanted to face it with them. “Anyone who flies operationally is crazy,” Egan confided to Sgt. Saul Levitt, a radioman in his squadron who was later injured in a base accident and transferred to the staff of Yank magazine, an army publication. “And then,” says Levitt, “he proceeded to be crazy and fly operationally. And no milk runs….”

When his “boy-men,” as Egan called them, went down in flaming planes, he wrote home to their wives and mothers. “These were not file letters,” Levitt remembered. “It was the Major’s idea they should be written in long-hand to indicate a personal touch, and there are no copies of these letters. He never said anything much about that. The letters were between him and the families involved.”

Major Egan was short and skinny as a stick, barely 140 pounds, with thick black hair, combed into a pompadour, black eyes, and a pencil-thin mustache. His trademarks were a white fleece-lined flying jacket and an idiomatic manner of speaking, a street-wise style borrowed from writer Damon Runyon. At twenty-seven, he was one of the “ancients” of the outfit, but “I can out-drink any of you children,” he would tease the fresh-faced members of his squadron. On nights that he wasn’t scheduled to fly the next day, he would jump into a jeep and head for his “local,” where he’d gather at the bar with a gang of Irish laborers and sing ballads until the taps ran dry or the tired publican tossed them out.

“Their fear wasn’t as great as ours, and therefore was more dangerous. They feared the unknown. We feared the known.”

Major Gale W. Cleven

When Egan was carousing, his best friend was usually in the sack. Major Gale W. Cleven’s pleasures were simple. He liked ice cream, cantaloupe, and English war movies; and he was loyal to a girl back home named Marge. He lived to fly and, with Egan, was one of the “House of Lords of flying men.” His boyhood friends had called him “Cleve,” but Egan, his inseparable pal since their days together in flight training in the States, renamed him “Buck” because he looked like a kid named Buck that Egan knew back in Manitowoc, Wisconsin. The name stuck. “I never liked it, but I’ve been Buck ever since,” Cleven said sixty years later, after he earned an MBA from Harvard Business School and a Ph.D. in interplanetary physics.

Lean, stoop-shouldered Gale Cleven grew up in the hardscrabble oil country north of Casper, Wyoming, and worked his way through the University of Wyoming as a roughneck on a drilling crew. With his officer’s cap cocked on the side of his head and a toothpick dangling from his mouth, he looked like a tough guy, but “he had a heart as big as Texas and was all for his men,” one of his fliers described him. He was extravagantly alive and was easily the best storyteller on the base.

A squadron commander at age twenty-four, he became a home-front hero when he was featured in a Saturday Evening Post story of the Regensburg Raid by Lt. Col. Beirne Lay, Jr., later the co-author, with Sy Bartlett, of Twelve O’Clock High!, the finest novel and movie to come out of the European air war. The Regensburg-Schweinfurt mission of August 17, 1943, was the biggest, most disastrous American air operation up to that time. Sixty bombers and nearly 600 men were lost. It was a “double strike” against the aircraft factories of Regensburg and the ball bearing plants of Schweinfurt, both industrial powerhouses protected by one of the most formidable aerial defense systems in the world. Beirne Lay was flying with the Hundredth that day as an observer in a Fortress called Piccadilly Lilly, and in the fire and chaos of battle he saw Cleven, in the vulnerable low squadron—the so-called Coffin Corner, the last and lowest group in the bomber stream—“living through his finest hour.” With his plane being shredded by enemy fighters, Cleven’s co-pilot panicked and prepared to bail out. “Confronted with structure damage, partial loss of control, fire in the air and serious injuries to personnel, and faced with fresh waves of fighters still rising to the attack, [Cleven] was justified in abandoning ship,” Lay wrote. But he ordered his co-pilot to stay put. “His words were heard over the interphone and had a magical effect on the crew. They stuck to their guns. The B-17 kept on.”

Beirne Lay recommended Cleven for the Medal of Honor. “I didn’t get it and I didn’t deserve it,” Cleven said. He did receive the Distinguished Service Cross but never went to London to pick it up. “Medal, hell, I needed an aspirin,” he commented long afterward. “So I remain undecorated.”

The story of Cleven on the Regensburg raid “electrified the base,” recalled Harry H. Crosby, a navigator in Egan’s 418th Squadron. Johnny Egan had also fought well that day. Asked how he survived, he quipped, “I carried two rosaries, two good luck medals, and a $2 bill off of which I had chewed a corner for each of my missions. I also wore my sweater backwards and my good luck jacket.” Others were not so fortunate. The Hundredth lost ninety men.

Casualties piled up at an alarming rate that summer, too fast for the men to keep track of them. One replacement crewman arrived at Thorpe Abbotts in time for a late meal, went to bed in his new bunk, and was lost the next morning over Germany. No one got his name. He was thereafter known as “the man who came to dinner.”

With so many of their friends dying, the men of the Hundredth badly needed heroes. At the officers club, young fliers gathered around Cleven and Egan and “watched the two fly missions with their hands,” Crosby wrote in his memoir of the air war. “Enlisted men adored them,” and pilots wanted to fly the way they did. With their dashing white scarves and crushed “fifty-mission caps,” they were characters right out of I Wanted Wings, another Beirne Lay book, and the Hollywood film based on it, which inspired thousands of young men to join the Army Air Corps. They even talked like Hollywood. The first time Crosby set eyes on Cleven was at the officers club. “For some reason he wanted to talk to me, and he said, ‘Taxi over here Lootenant.’”

Cleven liked the young replacements but worried about their untested bravado. “Their fear wasn’t as great as ours, and therefore was more dangerous. They feared the unknown. We feared the known.”

On the morning of October 8, 1943, an hour or so before Johnny Egan stepped on the train that brought him to London on his first leave from Thorpe Abbotts, Buck Cleven took off for Bremen and didn’t return. Three Luftwaffe fighters flew out of the sun and tore into his Fortress, knocking out three engines, blowing holes in the tail and nose, sheering off a good part of the left wing, and setting the cockpit on fire. The situation hopeless, Cleven ordered the crew to jump. He was the last man out of the plane. When he jumped, the bomber was only about 2,000 feet from the ground.

This was at 3:15 P.M., about the time Johnny Egan would have been checking into his London hotel. Hanging from his parachute, Cleven saw he was going to land near a small farmhouse “and faster than I wanted to.” Swinging in his chute to avoid the house, he spun out of control and went flying through the open back door and into the kitchen, knocking over furniture and a small iron stove. The farmer’s wife and daughter began screaming hysterically, and in a flash, the farmer had a pitchfork pressed against Cleven’s chest. “In my pitiful high school German, I tried to convince him I was a good guy. He wasn’t buying it.”

That night, some of the men in Cleven’s squadron who had survived the Bremen mission walked to a village pub and got extravagantly drunk. “None of them could believe he was gone,” said Sgt. Jack Sheridan, another member of Cleven’s squadron. If Cleven “the invincible” couldn’t make it, who could? But as Sheridan noted, “missing men don’t stop a war.”

The next morning, over a hotel breakfast of fried eggs and a double Scotch, Johnny Egan read the headlines in the London Times, “Eighth Air Force Loses 30 Fortresses Over Bremen.” He sprang out of his chair and rushed to a phone to call the base. With wartime security tight, the conversation was in code. “How did the game go,” he asked. Cleven had gone down swinging, he was told. Silence. Pulling himself together, Egan asked, “Does the team have a game scheduled for tomorrow?”

“Yes,” came the reply.

“I want to pitch.”