PhotoGRAPH by Reggys Santos

Off the grid

In the pursuit of a fully sustainable island, the College is helping to carry out the extraordinary vision of an engineer and environmentalist who graduated from Lafayette a century ago.

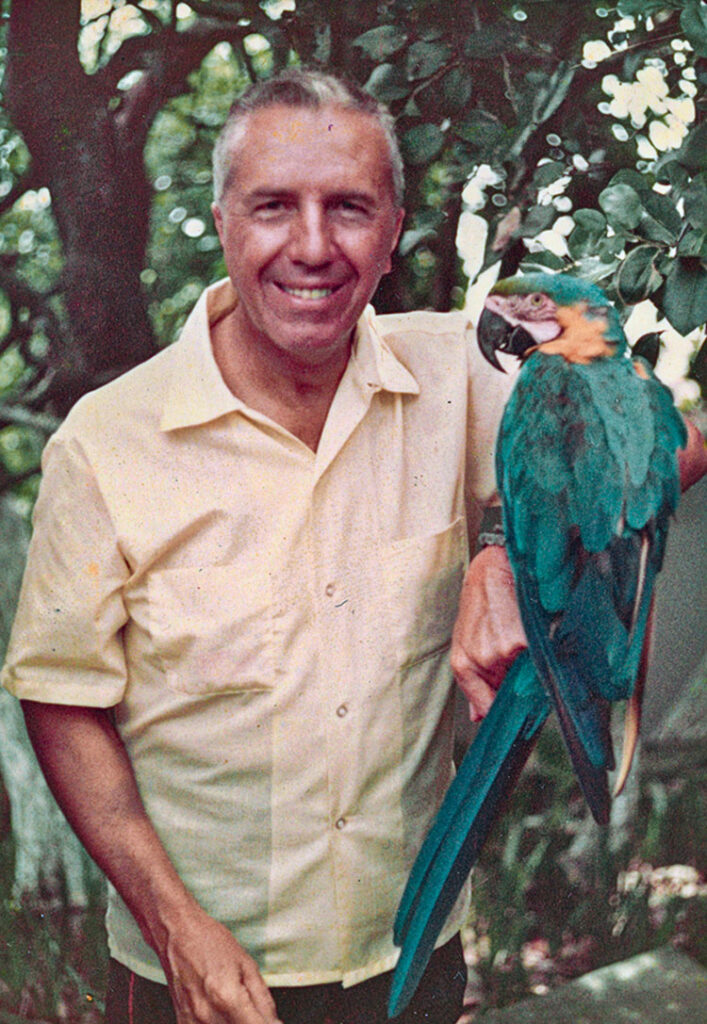

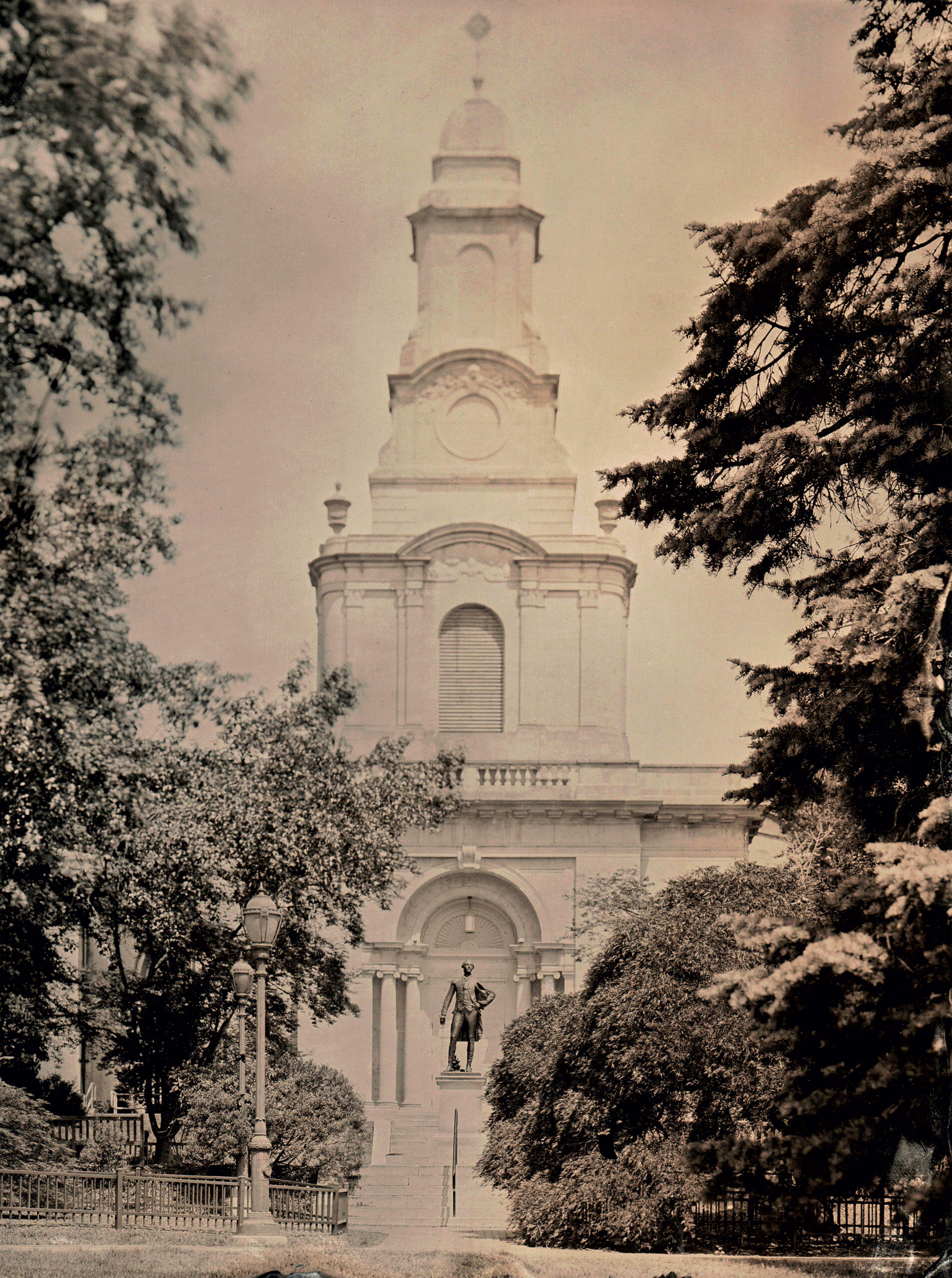

Technically, the eco-adventure started last September, when Mark Lebl ’94 reached out to Janine Block ’94, assistant director of intercultural development and international student advising. Lebl was traveling to the U.S. from his home in São Paulo, Brazil, and was passing through Easton. He told Block that he wanted to meet with the Engineering Division and share a story about a Brazilian named Fernando Lee, who studied mechanical engineering and graduated from Lafayette in 1924.

Lebl grabbed coffee with Lauren Anderson ’04, William Jeffers Dean of Engineering, at Mojo Café. Over the next 40 minutes, he explained how Lee, in the 1950s, had acquired a 100-year lease of an island, located off the southeastern coast of Brazil, for scientific research. The island was called Ilha dos Arvoredos, or an “island of thickets,” but there weren’t always trees there—the island was uninhabited and barren rock until Lee, an environmentalist with a vision, designed an entire ecosystem on it. “The island is a gem in the Atlantic Ocean,” Lebl says, “and it was made by a Lafayette alum.”

When Lee was in his 50s, he began building the paradisiacal property, which included a modest house made with reused stones from the island. He was one of the first in South America to use solar panels and had a piping mechanism on the roof to collect rainwater. “Lee wanted to create a wholly sustainable island before we were talking about the principles of sustainability,” Anderson says. “He saw things that other people didn’t and was able to innovate in a way that we now appreciate.”

However, Lebl told Anderson that because the island has been untended since Lee passed away in 1994, parts of its infrastructure require renovation, specifically its water and energy systems.

PHOTOGRAPH (ABOVE) BY REGGYS SANTOS. PHOTOGRAPHS (BELOW) BY DAVID BRANDES AND LAUREN ANDERSON.

After thinking it over, Anderson identified an opportunity. The Fund for Education Beyond the Classroom, an endowment fund established by Walter “Bud” Scherr ’78, could facilitate an educational trip during spring break 2024 for students in Environment and Energy Systems Engineering, taught by David Brandes, professor of civil and environmental engineering and Walter A. Scott Chair of Integrative Engineering. “I thought his class would be the perfect playground,” Anderson says.

Guided by the Fernando Eduardo Lee Foundation and the nonprofit Instituto Nova Maré (INMAR), the class began studying the island. One course theme is systems thinking, or tackling problems with a holistic, interdisciplinary framework, making the island’s nexus of water, energy, and food a natural fit for learning. “It was an opportunity for not just the students, but also for the College of Engineering to start to build a partnership with these folks,” Brandes says.

By revitalizing Arvoredos Island, making it a destination for ecotourism and marine research, residents on the mainland might benefit from sustainability initiatives as well, from river cleanups to pollution control. “It wouldn’t be crazy to speculate that if the island is fully running and if they have a business plan that is profitable, there would be money to reinvest in the local community,” Anderson says.

Lee’s vision and commitment to the environment has put the island in a promising position: The site has already met enough sustainability criteria that it was recently acknowledged as the first Green Key tourist attraction in the Americas.

And so, in March, a century after Lee graduated from Lafayette, eight students and three faculty members from his alma mater—Anderson, Brandes, and Prof. Michael Senra, program chair for the dual degree program in engineering and international studies—boarded a plane to Brazil.

Lebl put together the itinerary, met the group at the airport, and served as the host and translator for the trip. (“Without him, none of this would have happened,” Anderson says.)

One of their first activities was visiting the local college in Guarujá to learn more about Lee and the origins of the property. They also had a guide from INMAR, who took the group on a boat tour of mangroves in the area and a nearby impoverished fisherman’s village.

On Wednesday at 9 a.m., the group climbed into the boat for Arvoredos Island. They were joined by S. Maarit Cruz ’96, who works in the sustainability division of General Motors in Brazil, and embarked on the 15-minute ride over to the island.

Anarrow retractable ramp let down into the water and led guests to the dock. “It was Fernando Lee’s vision that this island was going to be a living, learning, open research laboratory,” Anderson says, explaining that meant people from all over the world could come and learn about sustainability practices and alternative energy technologies. “He has created something like a world site,” Lebl says.

Since he was originally building on rock, Lee needed a lot of soil; he also imported erosion-resistant grass from South Korea and, over time, planted purposeful flora and fauna. He curated the landscape with palm trees for shade and wind protection, and special orchids to filter rainwater in its root system, plus fruit trees (papayas, mangoes) and a coconut grove. Birds were brought in that wouldn’t fight with each other, like chickens and pheasants. A primary source of energy was a wind turbine atop a lighthouse that converted sea breezes into electricity. “You realize how much time he took to sculpt all of these features,” Brandes says. “He was someone with a lot of vision.”

Once docked, the students took to foot and got to work. “We needed a firsthand look at all of the different pieces,” Brandes says, explaining that he was eager for students to start measuring and collecting data from all of the existing systems. Some students were tasked with checking out how wastewater was naturally filtered; other students evaluated the electricity setup with (now defunct) wind turbines and solar panels.

The most critical necessity for living on the island is having drinkable water. Currently, collected rainwater moves from a reservoir into a grotto area and is pumped into tanks, where chlorine tablets are used to treat bacteria. It’s an unreliable system—island visitors are still required to bring bottled water—so students gathered information to identify better options.

Measuring dimensions and distances was key. Variables, for example, included the vertical elevations between the water tanks and where the water is ultimately used, as well as the diameter of the pipes (narrow pipes mean more friction and less flow). “The pressure and the flow are dependent on how much gravity you have driving the system,” Brandes says.

This fall, Dean Gennosa ’25 will be taking such data and working on an independent study project under the guidance of Brandes. Through pilot testing of water-purification technologies—including UV treatment—in an Acopian lab, he’ll be treating bacteria and removing sediment, with the hopes of installing a better solution on the island. (Coming up with a final design will be the basis of his capstone course in civil engineering.) Says Brandes: “We want to make sure our technology is tested in the lab and will work as an off-grid solution.”

Lee had used a crane to lift materials and goods up onto the island (pictured, above, with Senra, Anderson, and Brandes). Its diesel engine is inoperable, but students determined what kind of electric motor, powered by solar energy, could get it running again. They sourced the new equipment and suggested an enclosed and secure location to protect it from tampering and weather damage.

Serving as a counterweight to the crane is the massive Phoenix, made from 70 tons of concrete, which doubles as a large-scale art sculpture (pictured, left). “Some engineers have trouble understanding how he made the Phoenix,” says Lebl, explaining that it has endured decades of weather and is still in great shape. As one of the most distinguishable features of the island, the Phoenix tower rises above arriving guests and sets the tone about the aesthetics of Lee’s design. “To me, it looked a little bit like the Concorde,” Brandes says. “For somebody to invest that much in this little private island—it was really impressive.”

Around the island are several reservoirs, each with a different shape and purpose. A rectangular tank was to store boats. Another recreational pool, for swimming, fills with seawater at high tide. There was a pond for tilapia. Students sampled and tested the water quality at each of the reservoirs.

“This was a great opportunity for these students to think more about sustainable development in other settings, countries, and cultures,” Brandes says. International fieldwork, as the students learned, comes with added educational benefits like broadening perspectives, finding solutions that aren’t based in U.S. technology or engineering, and bonding with academic peers. “The students, professors, and alumni blended beautifully,” Lebl says. “I was so proud to be a part of that group.”

Having community-based learning was meaningful as well. “It’s an experience that really brings out the best in these students,” Brandes says. “They saw the importance of the work they were doing.” The hope, he adds, is that this is the start of a long-term relationship.

When the ES 303 class got back to Easton, they worked on various components of the project and presented their recommendations for improvements in May. Future steps could mean drafting business plans, participating in summer internships, or implementing the proposed engineering work.

Senra already has a return trip planned for a week during January’s interim session. In addition to revisiting ongoing projects on the island, he and students will explore other sustainability work and possible lines of corporate funding around the city of São Paulo.

Anderson brought a Lafayette flag and fastened it to Lee’s lighthouse; there’s optimism about the budding partnership between the College and this island of sustainability. Says Anderson: “The experience really exemplifies what we’ve redefined as our mission and values as a college—being responsible citizens of the world and offering transformational experiences that bridge studies.”