An Experimental Life

Most teaching artists introduce themselves to campuses by showing slides of their works. Curlee Raven Holton introduced himself to Lafayette by showing slides of his life as a work of art. On a warm autumn day in 1991, spectators in Room 108 of Williams Center for the Arts saw a projected picture of his father walking across the Mississippi farm where he harvested cotton and watermelons. They also saw an image of the ruined stone fence by the farm’s log cabin, in which Holton was delivered by a midwife.

It was a lecture and a sly manifesto, Holton’s way of saying that he was much more than the College’s fourth African American faculty member at the time, hired after a campus-wide search for a teacher of an African American course. “I wanted to show people I wasn’t a diversity agent, this Grand Poobah of blackness,” he says in his studio, a stone building on a hill outside Easton that was first opened in the 19th century as a school for Caucasian kids. “I was essentially telling them: You see me on television, on news shows. You don’t think I come from anywhere. I come from somewhere. I am my own invention.”

Five years later, Holton turned his manifesto into Lafayette’s Experimental Printmaking Institute (EPI), a laboratory for inventing and reinventing—artistically, technically, spiritually. For a quarter century he’s supervised a uniquely hands-on, hands-off open-door shop for collaborating with students, community volunteers, and scores of artists—black, white, Native American, Asian, South American, professional, amateur. Working in a former Plant Operations storage garage, EPI teammates have produced more than 300 prints and 150-plus print editions with subjects ranging from imprisonment to liberation while using materials such as a curtain and parachute fabric. EPI’s studio has been nicknamed everything from the “Collab Lab” to the “Ink Think Tank.” Melvin Edwards, one of EPI’s most distinguished and busiest artists, has called it “the next best thing to heaven.”

This May, Holton plans to retire from Lafayette after 26 years to pursue more personal communal projects. For EPI’s 20th anniversary last year, he was honored with a pair of EPI exhibits and a book chronicling EPI’s history. What follows is a tribute arranged as a textual print, a profile in plates of his many roles. It illustrates the imprint of an ecumenical missionary who believes “everyone has a story to tell; everyone has a genius to bring to the table, or the press.”

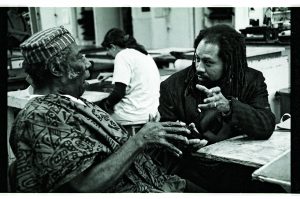

Robert Blackburn (left) and Curlee Raven Holton, 1993, at the Printmaking Workshop, New York City

First Plate: The Teacher

Coty West ’16 was a 22-year-old returning to college after a year off when she took her first course with Holton, called “Materials and Methods.” Her first surprise came when he told the class to put away their erasers, one of their trustiest tools. Her first shock came when he insisted: “No line is a mistake; every line is a gesture for the complete story.”

The thought of eraserlessness “made me sweat; it made me go into panic mode,” says West. “But it gave me artistic freedom. My hand hasn’t stopped since then.”

Holton had other ways of liberating West’s imagination. He stimulated her creativity by playing jazz and hip-hop records, drawing the same models as she did, subjecting his works to the same critiques as hers. He assigned her challenging projects, including a portrait of an artist’s grandmother in a wheelchair printed on a curtain. He encouraged her to be more daring in her honor’s thesis, a room-sized installation with relics—a fuse box, singed rafters—from a childhood house that had burned down.

Today West is a teaching assistant at EPI. She tells her students, young and elderly alike, she’s a junk artist, a print-carrying member of a family that owns a junkyard. And, yes, she asks them to free their hands and minds by erasing their erasers.

Chris Tague ’00 first heard Holton speak during an arts club meeting. He was immediately impressed: “I thought: Oh, this is what it means to be a serious artist who sees the world broadly, through a unique lens.” Inspired by Holton, he decided to major in art. He became an EPI fixture, working summers in a non-air-conditioned space he calls a “crucible.” Assisting a digital-print project led him to make videos, which then led him to work for Apple.

“Curlee was the best teacher I had at Lafayette,” says Tague, a research and analytics manager for Apple. “He taught me a lot about process, about working with people, about the value of doing things the hard way, the value of, frankly, failure. He taught me that it’s important to give people enough information to get the job done properly, while leaving out enough information to make them think for themselves. He helped teach me how to lead people.”

Second Plate: The Networker

Holton came to Lafayette as a veteran organizer. In Cleveland, his hometown, he had operated a gallery and hosted a multitude of artists in classes he taught at newly segregated public schools. His contacts expanded during a 1989-91 stint in the Manhattan studio of Robert Blackburn, master printmaker and Harlem Renaissance alumnus. It was Blackburn who gave Holton the mantra: “Everyone has a log to add to the wood pile.”

Holton wasted little time in building a printmaking wood pile at Lafayette. In 1993, he began issuing collaboration invitations to well-known creators brought to campus through the Grossman Visiting Artist and Exhibition Series. His first Grossman partner was Faith Ringgold, fabled for her vibrantly colored, radiant quilts of African American stories. She was talking to Lafayette students when Holton offered her a freshly ground zinc plate. She continued talking as she drew her young alter ego, Cassie, soaring over the George Washington Bridge, a symbol of freedom for Ringgold when she was growing up in Harlem.

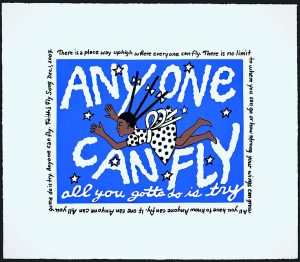

Faith Ringgold

(American, born 1930),

Anyone Can Fly (All You Have to Do Is Try), 2007

serigraph

Image: 10 x 12 3/8 inches

Sheet: 15 1/4 x 17 1/2 inches

Edition: 50

Four years later that drawing became the etching Anyone Can Fly, EPI’s first signature print. It was the first of more than 80 prints and portfolios Ringgold has made with EPI, with subjects ranging from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham City Jail” to a 9/11 flag. One of EPI’s Ringgold prints became a top seller at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; another was presented as a gift to Oprah Winfrey, the artist’s friend, for her last talk show.

Holton kept upping the ante over the next decade. He supervised an exchange program with art-book makers from Costa Rica; a two-year project matching eight master printmakers with eight master printers; a 2,000-foot-long print marking EPI’s 10th anniversary.

Third Plate: The Fundraiser

In 1995, Holton sat in an Easton restaurant pitching the idea of an experimental printmaking institute to Alan Pesky ’56, then a key member of Lafayette’s Board of Trustees and a longtime philanthropist with his wife, Wendy. At one point Pesky asked Holton how much he needed to seed his institute. Holton said $5,000, remembering that Pesky had told him his father had willed that amount to him and his brother. Pesky promised the money, which would fund a lithograph press and artist residencies. Holton promised to make Pesky’s money profitable. “I’m the kind of wild stallion,” he said, “that if you get me on the track, I’ll win the race.”

Four years later Holton helped Chris Tague convince his parents it was profitable for him to major in art and pull prints in a sweatbox. Holton made sure guest artist Ulysses Marshall worked closely with Tague, to give Harold and Janet Tague the impression that their son was “the captain of the ship.” It was an example of Holton playing “the pseudo-parent who approves, who offers a nonjudgmental space.”

Tague’s parents were so pleased, they became EPI patrons. Soon after their studio visit, they sent a check for $20,000 to buy an etching press. Later donations from the couple funded a blowout sink and artist residencies. Janet also has donated EPI prints to Mount Holyoke College, where she’s a trustee. She’s essentially turned her alma mater into an EPI satellite.

Fourth Plate: The Artist-Opportunist

Holton started EPI with two main goals. He wanted to expose students to a rainbow coalition of styles, techniques, and personalities. And he wanted better company for himself.

Since then Holton has made EPI his platform and launching pad. He’s pushed himself as a printer, helping Ringgold create a print with 11 colors on one plate instead of the conventional 11 colors on 11 plates. He’s pushed himself as a printmaker, making a 6-foot-long accordion book featuring such Lehigh Valley characters as his late neighbor Ernest Vargo, who, recalled his dairy-farmer parents helping the down-and-out during the Depression. He’s pushed himself as a producer, guiding the fabrication of Melvin Edwards’ Transcendence, a 16-foot-high stainless-steel sculpture placed near Skillman Library. Securing $100,000 from the College and $50,000 from the sale of limited-edition EPI prints, Holton shepherded an homage to physician David Kearney McDonogh, a former slave who in 1844 became Lafayette’s first African American graduate.

EPI has linked Holton to significant ventures off College Hill. He made etchings of Othello as a visiting artist at a printmaking studio in Venice, the hometown of Shakespeare’s towering, tragic general. He leads debates about aesthetics, economics, and politics as the executive director of University of Maryland’s center for studying visual arts and the African diaspora. He helps a New Jersey police chief acquire works by African American artists to help promote law and order, tolerance, and citizenship.

It’s all part of Holton’s campaign to use art as a battlefield, a sanctuary, a school. “I like to move an issue from the background to the foreground,” he says. “To reveal things hidden in the shadows. To see the unseen world of affinities and associations within all of us.”

Lafayette College EPI students deliver Oprah We Love You, 2011, print to Faith Ringgold at Ringgold’s New Jersey studio.

Fifth Plate: The Bent Arrow

Holton’s biographical résumé reads like a blueprint for the experimental, egalitarian shop.

Born in a farmhouse without running water in DeKalb, Miss. Descended from Scottish immigrants and Choctaw Indians who intermingled with runaway slaves. Moved to Cleveland after his father got a job at a drop forge. Grew up with Jewish and Greek friends. Met artist Romare Bearden, filmmaker Gordon Parks, and other black visionaries at the Settlement School, a venerable cultural center in Cleveland.

Chris Tague ’00

(American, born ca. 1978)

Hotel Easton, 2001, digital print

Image: 17 1/2 x 12 inches

Sheet: 22 1/2 x 15 inches

Edition: 30

In the Army, learned to march with his head up, a liberating act for a man of color. Attended night school at Cleveland Institute of Art. Met his wife, Glee Ivory, through the Cleveland public school system, which she helped integrate as a court-appointed monitor. Embraced printmaking as a vehicle for deeply personal expression, social protest, and a second language.

Holton calls himself “a bent arrow.” He’s made EPI a home for other folks whose flight path isn’t a straight course.

Jessica McRorie ’00 came to Lafayette as a mechanical engineering major and left with an English degree. EPI, she says, enabled her to fuse her interests in science and literature, precision and passion. Holton taught her that she could make her mark on a print by aligning and shading; by collaborating creatively she could be a character.

Holton’s advice continues to guide McRorie, a former newspaper reporter who handles public information for the New York City Police Department. Her brain loops with his gospel creed: If you want to make the walls of adversity crumble, you have to blow your horn with loud confidence.

Sara Smith-Katz ’07 came to EPI in her 40s, a jewelry specialist, real-estate agent, and mother of two youngsters. She relishes the memory of watching creation of a drawing by Mel Edwards, Sam Gilliam, and William T. Williams, three of the legendary Four Horsemen. She treasures talks with Holton about growing up in a racially divided town and family. Her mother discouraged her from going to the prom with a black student; her father discouraged her from celebrating her Native American heritage.

Smith-Katz promoted EPI by starting an ink club. She promotes the institute as a substitute arts teacher at a private school. Her daughter Hannah works at EPI, a bent arrow who boomerangs.

One of Holton’s oldest EPI allies is Riley Temple ’71—Virginia native, owner of a wealth-management company, AIDS activist, founder of a theater company, board member of the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. In 1996, Temple started an EPI fund for lectures and residencies, fulfilling his obligation as a Lafayette trustee to contribute to the College’s capital campaign. The American studies graduate has enjoyed bringing the likes of Faith Ringgold and Sam Gilliam to the school where he heard Ralph Ellison discuss his novel The Invisible Man during The Black Man in Civilization class, where he discovered the eye-elevating, soul-lifting wonders of architecture.

Curlee Raven Holton, Clifford Charles, and Melvin Edwards, 2011

Temple considers Holton an ideal teacher: kind, wise, inspirational, innovative. The EPI founder, he says, has made him a more astute student of art, which has made him a better collector. He wants to return the favor by involving Holton in creation of a counter narrative to windows in the Washington National Cathedral that honor Confederate generals Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee, who fought the Civil War to save slavery. Riley envisions an art project celebrating the path of African Americans from slavery to freedom, darkness to light, perimeter to center stage.

Sixth Plate: The Printer

It was Temple who recruited one of EPI’s most pre-eminent partners: David Driskell, an 85-year-old native of Georgia and pioneering scholar, curator, collector, and broker of works by African American artists. He’s renowned enough to have his name on the African diaspora center that Holton leads.

An acclaimed artist, Driskell credits Holton for helping him successfully unite tricky oil-and-water elements — watercolor, egg tempera, encaustic — while indulging his fondness for found pieces of wood that could stress EPI’s presses. Holton not only improved his printmaking, Driskell says, but heightened his awareness of the importance of his work. He had an epiphany of sorts when Holton told him: “You know, a lot of people make prints, but we make art.”

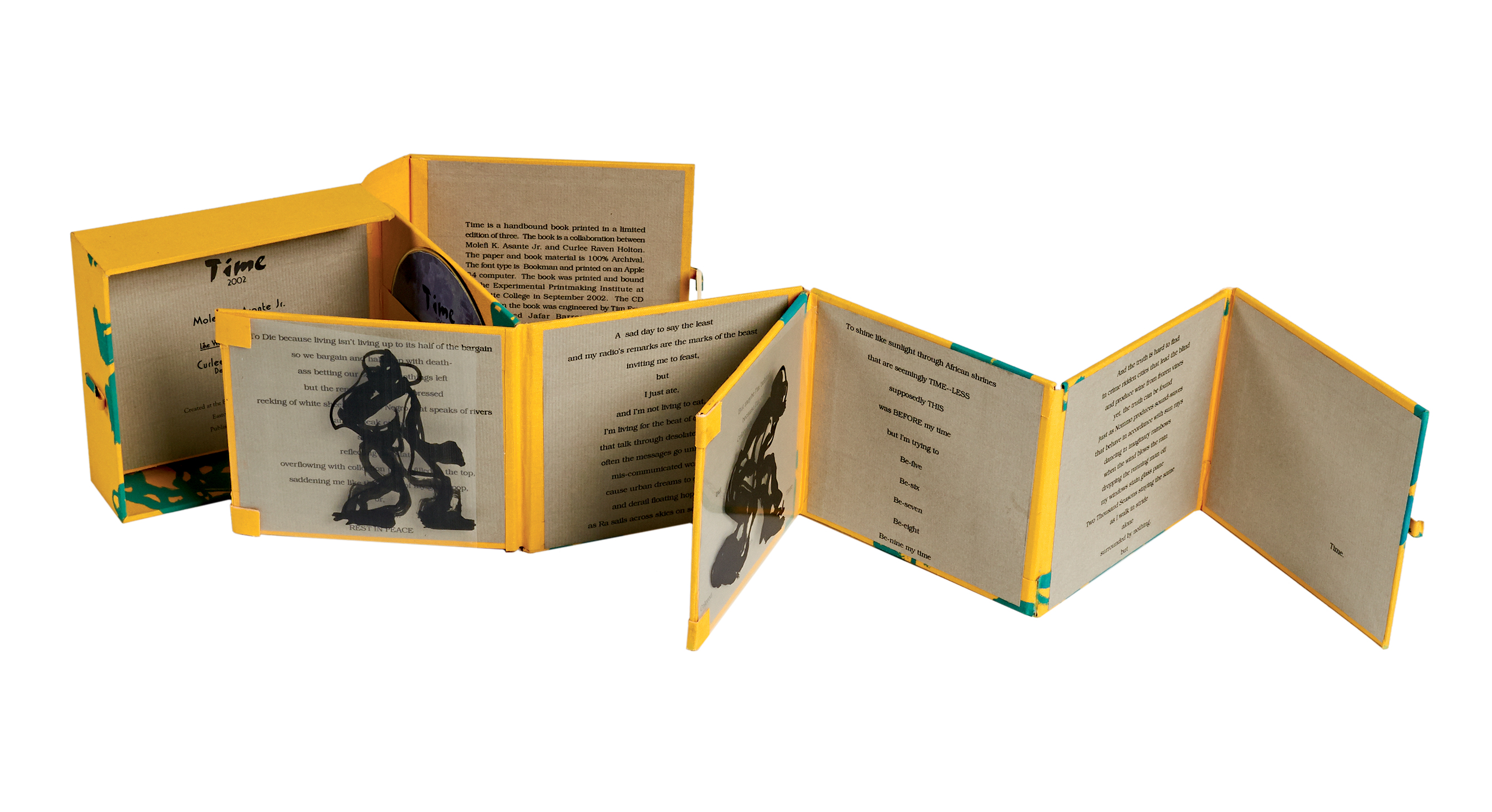

Curlee Raven Holton (American, born 1951) with M.K. Asante (Zimbabwean, born 1982) Time, 2003,mixed media, digital, CD. Book closed:5 3/8 x 5 7/8 x 1 3/4 inches. Book opened:5 3/4 x 5 7/8 x 35 inches extended Edition: 3

Seventh Plate: The Imprinter

Holton sits in Atelier Raven, his schoolhouse studio on Morgan Hill, tracking places that bear his imprint. There’s the National Gallery of Art, which owns an edition of works by 16 EPI master printmakers and printers. There’s Lafayette’s Skillman Library, where the number of artist books acquired by the Department of Special Collections has increased over three decades from a handful to nearly 1,000. There’s Apple, where Chris Tague spreads the Holton-esque mantra: “Let’s make better mistakes tomorrow.”

Holton’s tomorrow officially begins this spring, after he retires from Lafayette. The death three years ago of his sister, Edna Pearl, made him realize he needed to pursue more personal communal projects. That means spending more time with his parents, who are in their 90s; his five children; and his wife, Glee, a senior officer for the Pew Charitable Trusts. That also means turning his property into an artist retreat. Jessica McRorie, his horn-blowing, backyard-barbecuing EPI protégée, has promised to help him build a spit for roasting pigs. n