On the Trail of General Lafayette

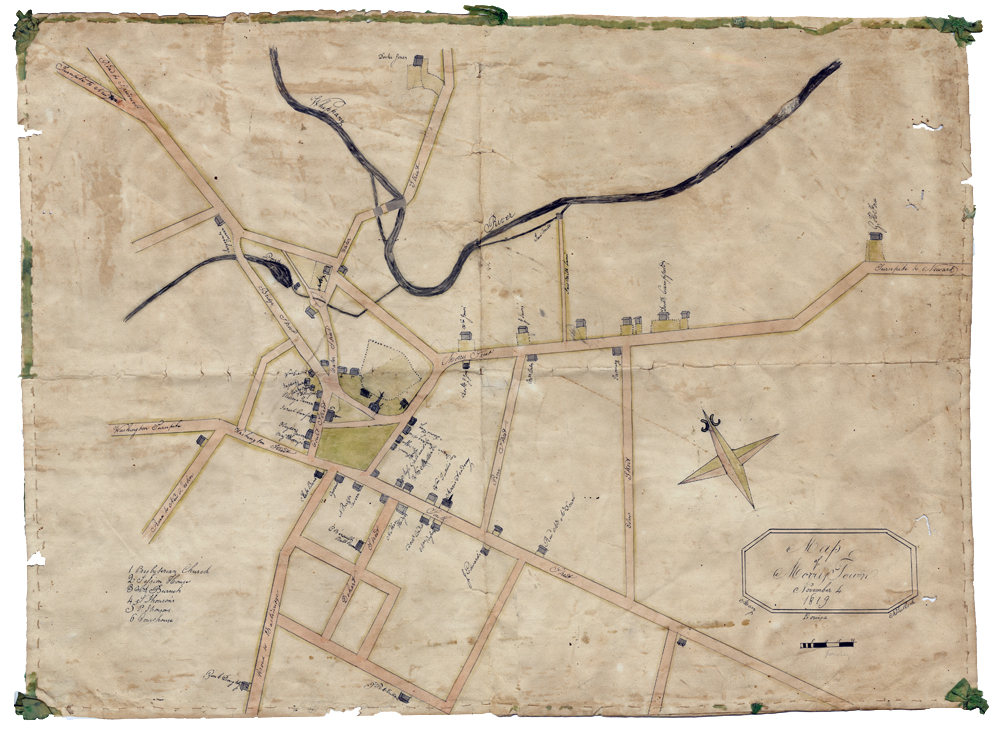

A young man leans over a map in the basement of the library in Morristown, N.J. Drawn by a school girl in 1819, the map is amazingly accurate to Google Maps standards, plotting the streets, homes, churches, and establishments in the southern part of the township.

He traces his finger along South Street, which leads to the town green. There at a T-intersection the Marquis de Lafayette was said to have dined at the Ogden House during his 1824-25 Farewell Tour of America.

1891 map of Morristown drawn by Louisa Macculloch Courtesy of North Jersey History and Genealogy Center at the Morristown and Morris Township Library

Was said. Those two words are the hook that have caught the young man.

“Was said” is not specific enough for Julien P. Icher, a 25-year-old native of France, who has spent half a year retracing the Marquis’ 1824 journey. Having covered 395 stops to date, Icher is nearly halfway through the tour and halfway through his travel visa.

So time is of the essence.

He has called ahead today, and the staff at North Jersey History and Genealogy Center have prepared a folder for him.

On the docket are three locations General Lafayette visited: Sansay House, where it was said a ball was held in his honor; Wood House, where he slept; and Ogden House, where he had dinner.Icher wants to know on which corner Ogden House stood and if the Marquis, in fact, ate there.

Once he confirms the Morristown stop, he is off to Trenton and Princeton. Yesterday he covered Jersey City, Newark, and Elizabeth.

Icher locates Ogden House on the map, snaps a picture of it, and asks for a scanned version. All of it will go on thelafayettetrail.org where Icher tracks his travels and discoveries.

And today is a day of discovery.

In the folder is a copy of an article from the July 13, 1825, edition of the Palladium of Liberty newspaper outlining the visit plans for the Marquis. The plans confirm what Icher already knows.

Icher has gained his knowledge of the tour from three primary sources: the journal of Auguste Levasseur, Lafayette’s personal secretary during the tour; James Bennett Nolan’s 1934 book Lafayette in America: Day by Day; and a collection of local newspaper coverage on the tour published in the 1944 book Pilgrimage of Liberty by Edgar Ewing Brandon along with three subsequent volumes he published in 1950-57 titled Lafayette Guest of the Nation.

But these sources can vary or, worse, offer conflicting reports, so Icher supplements this material with what he calls his boots-on-the-ground research.

As Icher quickly leafs through articles in the folder because he has seen the same articles or clippings before, he comes to a reference of the visit in the July 21, 1825, edition of Palladium. He asks the reference librarian to find him a copy.

When she brings out the original paper, Icher flips through pages until he comes to the article he seeks only to see that the old pages are thin, worn, and holey.

But back in the folder, deeper in the copies, is a facsimile of that edition of the paper. He reads aloud the General did go to Sansay House, where balls were often held, did dine at Ogden House on the southeast corner of Market Street and the town green, and did spend the night at Wood House.

“I am happy with this,” he says. “It may be hard to tell, but I am burning inside.”

Fueling the Burn

Icher is passionate about the Marquis, liberty, and French-American relations.

“Lafayette’s imprint in this country is much deeper than people understand,” says Icher. The general’s visits demonstrate a repeated pattern of people coming together. America at the time was deeply divided as the country expanded westward and slavery continued to drive much of the economy.

Julien Icher in Yorktown, Virginia.

When Lafayette arrived, the country was in the midst of a great political split. It was the first generation of leaders who were not forged from Revolutionary War times. During the Presidential election, if Andrew Jackson did not win, a group of southerners planned to march, weapons in hand, into Washington, D.C.

But those same southerners set down their weapons and picked up pints of ale to celebrate Lafayette. That political strife found across the nation paused during Lafayette’s visit—the tour was a moment to set aside differences and rally around the last “Founding Father of American democracy.”

“He was a unifying figure, and people swooned over him to a scale and extent that is hard to grasp,” says Icher. “Communities made major efforts to receive him and went wild upon seeing him. They would touch him for blessings.”

A woman at the Wood House in Morristown, as covered in the 1825 edition of the paper, said she would keep the sheets Lafayette slept on forever and never wash them.

“In America today there is only a parade for Super Bowl winners and for monumental occasions like landing on the moon,” says Icher. “Lafayette had a parade in nearly every town he visited.”

Holding a bachelor’s degree with majors in history and geography as well as two master’s degrees in geography and geographic information systems, Icher is using all three degrees on this trip as he reads, tracks, and documents discoveries.

His journey started in 2016 when Icher attended a garden party held for members of American Friends of Lafayette at the French Consul’s residence in Boston. There, after a conversation with Consul Valery Freland, Icher proposed the Lafayette Trail project. He was subsequently hired as an intern in the Consul’s office, and the actual journey to map the trail in New England began in March 2017.

American Friends of Lafayette (AFL) is the patriotic society formed at the College in 1932 to honor the Marquis.

The Lafayette Trail Project is an effort spearheaded by AFL and the Consulate of France in Boston to memorialize the footsteps of General Lafayette in preparation for the Bicentennial of the Farewell Tour in 2024.

The endeavor has caught some notable attention. In April 2018, Icher was invited to be a part of the French cultural delegation visiting the White House and U.S. Capitol for the French state visit. It was there that he was endorsed by French President Emmanuel Macron to extend his mapping from New England to all 24 states Lafayette visited.

But such a journey is no easy task … even Lafayette had a secretary to help him.

The AFL Bond

John Becica ’69 goes outside to feed the parking meter as Icher wraps up his time in the library. As Icher steps outside, Becica is waiting. Together they walk down South Street to where Ogden House and Wood House originally stood.

Icher pulls out a camera to snap pictures of the Starbucks (Ogden House site) and performing arts center (Wood House site).

Becica is chauffeur today, a role he has been playing all week as they trace Lafayette’s steps through New Jersey. In addition Becica serves as trail financier, hotelier, and chef as Icher stays at his home.

“Having met Julien at AFL events starting in 2016, I have come to regard him as a son or grandson,” Becica says.

Becica became fascinated with the Marquis about 20 years ago when he heard Diane Shaw, director of special collections and College archives, speak about Lafayette at the Chateau during a Lafayette Reunion Weekend. He was hooked and immediately signed up as a member of AFL.

The organization promotes the ideals of this great French visionary leader, the inspirational quality of his remarkable career, his contributions to America’s own struggle for liberty, and his ceaseless efforts to forge an eternal bond of friendship between the United States and France. The group publishes work on the Marquis and has donated nearly 2,000 artifacts to the College archive. (New members are welcome!)

Becica has become a walking historical master on Marquis facts. He is the perfect help for Icher, and AFL is a great supporter. While AFL membership only sits around 280, the group has supported the trail project to the tune of $86,000.

Beyond that is the moral support. In four months of travel and 10,000 miles on the car, Icher has only had to spend six nights in a hotel as AFL members as well as members of the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution open their doors to him.

Recently AFL commissioned a statue of Lafayette on the Yorktown, Va., waterfront to commemorate the American Revolutionary War victory. Ironically, Icher not only follows the Marquis’ footsteps but also models his footsteps. The sculptor used Icher’s measurements as a model for the Lafayette statue.

“Many do not understand the importance of Lafayette in our lives today,” says Becica. “He is the key figure in getting France to aid us in winning the Revolutionary War. Historians agree we would have lost the war and remained British subjects without Lafayette. He was the original spin doctor, soliciting French assistance as he wrote letters from America to his friends in the French aristocracy and to the King’s ministers.”

Trail Ahead

Icher and Becica soon hop in the car to head to Trenton. They expect to put 270 miles on their car today and probably 200 tomorrow.

As they go, they visit libraries, historical societies, and local press to remind citizens today about Lafayette and his role in our freedom.

“I am hoping that what we do here, in this country, may inspire similar endeavors in France,” Icher says. “Lafayette has sunk into oblivion in France as the national memory doesn’t recognize his achievements. Today the liberals don’t hold him up because he supported the monarchy, and the conservatives don’t embrace him because he was a troublemaker who championed the rights of the people.”

As both countries seem to be eschewing the politics of unity, documenting Lafayette’s journey could be an appropriate way to bring people, communities, and countries together—exactly Icher’s vision when he proposed the Lafayette Trail Project.