College Budget 101

by Annette Smith Parker | Infographics by Dale Mack

The American higher educational model is robust—no other educational system in the world provides such diversity of experience and opportunity. Nevertheless, in the last 10 to 15 years tuition costs have risen dramatically, and particularly at small private colleges and universities. Some of the factors include highly trained faculty members who provide a hand-tooled education in small classes, low student-faculty ratio, significant academic resources including technological infrastructure, library materials, and laboratory equipment, and support for residential life on beautiful campuses with counseling and career services and enhanced security staff.

The budget in the example presented here is of a nonprofit private institution, designated by law as “a purely public charity” because of the benefit it provides to society.* Nonprofit institutions are exempt from paying most taxes, can accept donations, and they provide financial aid to students, supporting those who would otherwise be unable to afford higher education.

[*NOTE: The example is based on averages and is not the budget of Lafayette College or any other existing college.]

Even though revenues equal expenses in the budgets of typical nonprofit institutions, the models span a broad spectrum. A community college, for example, might receive one-third or more of its revenues from sponsoring school districts and state appropriations. Large public institutions may receive support from medical facilities, research centers, or nationally broadcast athletics. Highly selective, private liberal arts colleges do not receive a significant amount of direct government support (though their students may). They do, however, depend on gifts, grants, and annual revenue from the interest on endowment funds to fill the gap between price and cost per student.

Many colleges have already taken steps to control the growth of costs and to find ways to maximize revenue. These initiatives often focus on shrinking administrative budgets, increasing payout from endowments, and improving fundraising. But some are exploring alternative revenue streams such as partnering with education companies to offer online language courses or offering post-baccalaureate programs. Others are forming consortiums to share resources.

Recognizing that these and other strategies hold promise for the future, college leaders are also finding ways to better articulate the value and distinction of the education provided at a private, small liberal arts college with a focus on mission integrated with market and value.

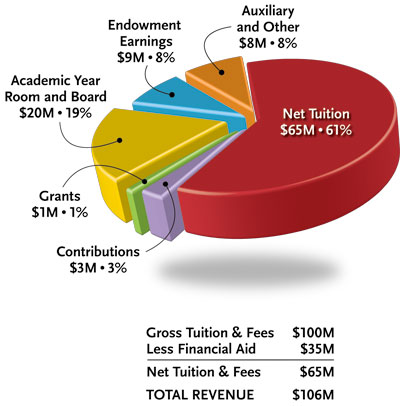

REVENUE

Although this fictitious college bills students $100 million in tuition, it derives only $65 million in net revenue after subtracting “the discount,” i.e., $35 million in financial aid. The discount rate, here 35 percent, is calculated by dividing financial aid by tuition. Although some liberal arts

Although this fictitious college bills students $100 million in tuition, it derives only $65 million in net revenue after subtracting “the discount,” i.e., $35 million in financial aid. The discount rate, here 35 percent, is calculated by dividing financial aid by tuition. Although some liberal arts

colleges have discount rates as low as 20 percent, many approach 50 percent. Higher discount rates put pressure on the operating budget, because only the “net” amount of tuition received is available to fund expenses.

The college in this example is “tuition dependent,” that is, total revenue from students — net tuition plus academic year room and board — supplies 80 percent of operating revenues.

Another 4 percent of revenue comes from contributions and grants, and 9 percent is derived from endowment earnings. More generously endowed colleges may receive 30 to 50 percent of revenue from endowment spending, providing them with far greater resources to enhance academic and residential programming, financial aid, and facilities.

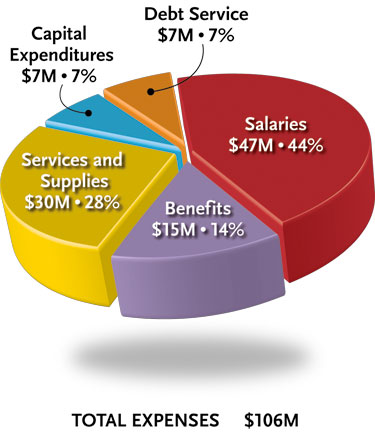

EXPENSES

Faculty and staff comprise the largest expense at most liberal arts colleges — in this example, 60 percent of total expenses.

Faculty and staff comprise the largest expense at most liberal arts colleges — in this example, 60 percent of total expenses.

Unlike an assembly line where machines can increase efficiency and decrease costs, the “master/apprentice” model of close engagement between professors and students discovering new knowledge together comes at a cost.

Expenses related to technology and facilities (maintenance, energy, building and equipment depreciation) also represent major commitments, as do increasing costs of safety, legal, and audit services, compliance, and regulation.

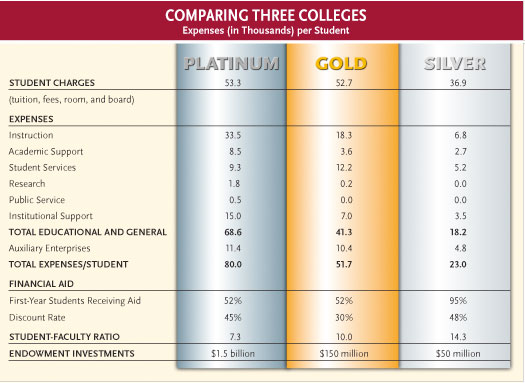

In the chart on page 15, three colleges are compared based on expenses per student. The additional resources provided by Platinum’s endowment enhance instruction and instructional support, for example, library and academic computing, as well as other expense categories. A low student-faculty ratio is evident at the highly endowed institution.

PRICE AND COST

Although Platinum’s sticker price (“charges” in the chart) is $53,300, the cost (“expenses” in the chart) of providing the educational and residential experience is $80,000. Thus, at Platinum, every student receives a $26,700 “subsidy” before any financial aid is considered. In contrast, Silver charges less per student, receives significantly less from endowment income, provides aid to 95 percent of first-year students, and immediately “rebates” 48 cents of every tuition dollar back to students in the form of financial aid.

Among highly selective, private liberal arts colleges, the difference between price and cost can vary widely, depending on endowment support. Many institutions record costs per student between $60,000 and $100,000, even though market forces currently cap price around $55,000 for one student for one year.

Maintaining price to the student around $55,000 when cost is tens of thousands of dollars higher is only possible because of the support provided to private college budgets by generous annual fund and endowment gifts.

Source: Lucie Lapovsky, “Tale of Three Campuses: A Comparison of Three Small Liberal Arts Colleges,” The Lumina Foundation, 2012.

Annette Smith Parker, founder and principal of Causeway Consulting LLC, a firm specializing in assessing outsourced investment office options for nonprofit clients, was chief financial officer at Dickinson College from 1998 to 2010.