Jul 11, 2014

Legal Career: Get Set

Pre-Law Advising: guidance and resources related to legal careers and law school applications Mock Trial Team: students collaborate on legal arguments…

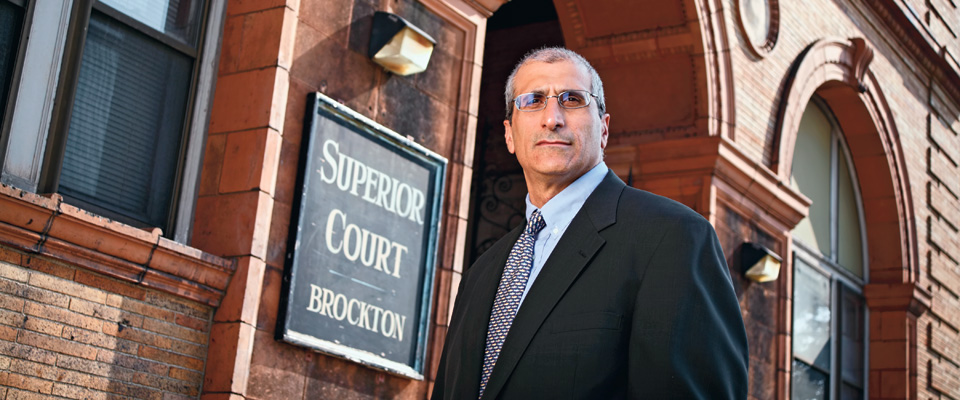

Among the many Lafayette alumni who have distinguished themselves in judiciary careers is Massachusetts Superior Court Judge Frank Gaziano ’86.

Photo by David Carmack

by Lori F. Hixon

Whether something is right or wrong is often characterized as black or white, but Judge Alvin Yearwood ’83 says the reality is many shades of grey.

“Recently, I sat in a court dedicated to human trafficking. It was no longer strictly a crime-and-punishment issue because the defendants who were charged with prostitution and other sex-related offenses may have been victims of human trafficking,” he says. “Obviously they are still defendants who are facing punishment in the court system. But over time, an understanding has developed that some of these defendants were forced into doing what they were doing. And telling someone ‘just say no’ isn’t going to work.”

Judge Alvin Yearwood ’83, Bronx County Supreme Court. Photo by Chuck Zovko

A judge in the New York City Criminal Court and acting Bronx County Supreme Court justice, Yearwood says while these defendants are being prosecuted, they also are being offered services. “Maybe the court is offering them help to finish their high school education. Maybe they need drug treatment. Maybe there’s some sort of a mental illness that has to be resolved through counseling. And, so, while they may end up being punished, they also get help to move past their current circumstances and out of that environment.”

Yearwood, an international affairs graduate with a law degree from Boston University, has worked in New York’s criminal justice system for 24 years. As a judge, he says, his goal is to see that justice is done. “It sounds simple, but it’s complicated at times. It requires a paradigm shift in thinking that moves away from just crime and punishment.”

In Howard County, Ind., a program begun by Superior Court Judge William Menges Jr. ’73 to break the cycle of drug addiction and crime takes that step beyond a court sentencing.

Defendants participating in the Adult Drug Court Program, established in 2007, may avoid criminal prosecution by agreeing to complete a substance-abuse treatment program, remaining alcohol and drug free, and completing other requirements determined by the drug court team and Menges. He recently launched a Reentry Program to support people released from incarceration.

“In the drug court program, we have about a 60 percent graduation rate and about 12.5 to 14 percent recidivism rate among graduates,” says Menges, a psychology graduate who earned his law degree at University of Tulsa. In the past three years, he adds, none of the graduates from the reentry program has relapsed, and the graduation rate is 60 percent.

This success is tempered by the full weight of his caseload. “The success rate is very rewarding, but I am still dealing with some dangerous people. And those people don’t end up in drug court. They end up in criminal court and the traditional criminal justice system, over which I also preside.”

Today’s judiciary is indeed about more than just crime and punishment. “Judges are not just dispensers of justice. They have to try to help people turn the corner,” says Robert Freedberg ’66, a judge in the Northampton County, Pa., Court of Common Pleas for 28 years, including 17 as president judge, after which he served four years on the Superior Court of Pennsylvania.

“The people I sentenced came from Easton, Bethlehem, and the neighboring communities. And, almost invariably, they came back to Easton, Bethlehem, and neighboring communities after their incarceration,” he says. “The relevant question for today’s judicial system is: When they return, are they going to be better people or are they going to be more dangerous people? Our judicial system had better be thinking about how we can make them better people.”

A government and law graduate to whom the College awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree in 2002, Freedman holds a law degree from Columbia University. He is now an attorney in the Bethlehem office of Florio Perrucci Steinhardt & Fader.

Since being appointed to the bench by then-Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney, Judge Frank M. Gaziano ’86 has strived to be the judge that he would want to appear before if the situation ever arose. Now a Massachusetts Superior Court judge, he says gang-related homicides are the most challenging of his cases.

“On one side, there is the emotional aspect, because often an innocent person has been murdered. You’re also dealing with someone who, if convicted, is going to be taken out of your courtroom and put in prison for the rest of his or her natural life,” says Gaziano. “Complex legal issues such as theories of murder arise as well as evidence questions involving witnesses who may or may not cooperate or who forget things, whether intentionally or not. Intimidation issues. Gang issues.”

William Menges ’73 is Superior Court judge in Howard County, Indiana. Photo by Chris Bergin

Every day Gaziano draws on his experience as a state and federal prosecutor. He also is guided by his Lafayette education. A government and law graduate, he holds a J.D. from Suffolk University.

“Jacob Cooke and Richard Welch gave me an appreciation for the law, particularly its influence on American history,” he says.

“Having that historical context is critical as you apply the law,” he says. “For example, I have to decide motions to suppress evidence all the time. The particularity requirement, which requires police requesting a search warrant to tell the magistrate what they’re looking for and where it could be found, is based on the prohibition against general warrants that happened in the U.S. colonies. As we litigate constitutional issues, we have to figure out the foundation for that constitutional prohibition.”

In a highly litigious society, the court system can become a bottleneck to justice. For James J. “Jim” Ryan ’56 more of his work took place outside of the courtroom than inside. He presided primarily over civil cases during almost 12 years on the bench as a Circuit Court judge in Cook County, Ill.

“With a docket of more than 15,000 cases, we were under tremendous pressure to move cases along,” he says. “In Cook County, we have an active arbitration procedure, through which many cases were settled. As a judge, you sit down, reason with the parties, and attempt to get them to settle their dispute. Arbitration is a far more successful way of handling a case than hearing it to its conclusion.”

“I was the first person in my immediate family to go to college, and there were a lot of things that I did not know. That’s why I mentor students and give them the benefit of my experience. When I entered the working world, there were people who looked out for me, became my mentors, and asked nothing of me. So the least I can do to repay them is to mentor those coming behind me.”

— JUDGE ALVIN YEARWOOD ’83 Bronx County Supreme Court

Ryan relied on wisdom gained during many years as a trial lawyer, often representing clients in complicated structural litigation, and his education in industrial engineering at Lafayette and law at University of Wisconsin.

“I have done a lot of things in my life, but being a judge was the most important. Society puts a great mantle on us. Judges are important—not in the personal sense, but in the sufficient operation of a constitutional government and freedom,” he says.

During his tenure, Freedberg also was instrumental in creating rehabilitation programs in the Northampton County Prison. “We’re fooling ourselves if we think that we can put offenders in a cell, lock the door, and that the problem is going to go away a few years later,” he says. “We had better be doing things to help.”

Occasionally in the community, Freedberg encounters an individual whom he has sentenced. “You might think that would be scary. But I’ve found that when people you’ve sentenced come up to you and want to talk, they typically want to tell you how well they’re doing and how they’ve changed their lives,” he explains.

Seemingly these individuals, who paid their debt to society, find solace in reassuring a person whom they respect and who was the springboard to their changed and more productive life.

Pre-Law Advising: guidance and resources related to legal careers and law school applications Mock Trial Team: students collaborate on legal arguments…

Government and law graduate Jason Goldfarb ’14 will take another step toward his goal of becoming a judge when he begins his studies at Georgetown University…