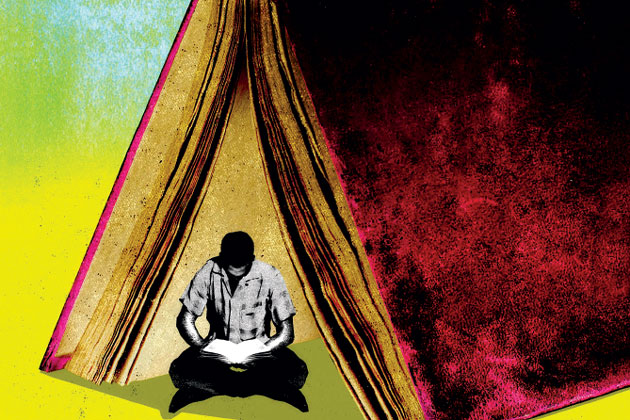

Common Books, Uncommon Bond

By Geoff Gehman ’80 | ILLUSTRATION BY BRIAN STAUFFER

By Geoff Gehman ’80 | ILLUSTRATION BY BRIAN STAUFFER

Last summer Brendan McNamara ’18 took a mini-course in discourse before he took a course on College Hill. Back home in San Diego he read Elizabeth Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, an assignment for Lafayette’s incoming new students. Then, during an on-campus orientation session, he and 500-plus classmates heard five teachers present very different spins on issues raised by Kolbert’s account of humans decimating plants, animals, and themselves. Over the next four months McNamara dove deep into the debate over endangered species. He contemplated the dramatic decline of the Peruvian rainforest and Pacific coral reefs.

He reviewed his peers’ exceedingly diverse opinions—everything from denying the existence of global warming to predicting human extinction caused by global warming. For his First-Year Seminar, 10 Ways to Know Nature, he wrote a paper on fracking, a controversial method of extracting gas and oil from rock, a process that angers his grandfather.

The extinction theme helped acclimate McNamara to college, country, and cosmos.

“It was an ice breaker, a talking point, an automatic connection,” says the former intern at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, home to rare northern white rhinos, another threatened tribe. “It made me more aware of people’s views, more aware of my surroundings, more aware of my impact on my surroundings.”

McNamara joined two generations of first-year Lafayette students with uncommon experiences triggered by common readings. Perspectives and paths have been changed by books tracking the racial politics of medicine, traumatized soldiers, evolution, and post-9/11 freedom of expression. Integrated with programs, exhibitions, and theater performances offered throughout the academic year, the common reading has become a free-floating seminar on public scholarship and citizenship.

“We’re saying: Here’s what you need to know about a liberal arts education and your place in it,” says Paul J. McLoughlin II, dean of students and co-director of new student orientation. “Here’s how you can use this education at the start of your first year and how you can use it for life.”

A 22-Year Tradition

Lafayette’s summer common reading began in 1992 with two polar-opposite books: Nadine Gordimer’s July’s People, a novel set in post-apartheid South Africa, and Michael Moffat’s Coming of Age in New Jersey, an anthropological study of his college-age students’ social, intellectual, and sexual habits. The latter was especially popular with 136 first-year students from New Jersey, some of whom undoubtedly felt they were peering at their peers’ diaries.

The Odyssey, the 1999 common book, linked the dawns of Western literature and the third millennium. Homer’s ancient epic received an electronic update via an Internet discussion board that allowed incoming first-year students to comment on and question Odysseus’ 10 years of adventures with gods, monsters, and sirens.

Posting from her home in Ghana, Shirley Anuse Satuh Kelly ’03 compared her 5,000-mile journey from Africa to America to Odysseus’ 5,000-mile journey from the Trojan War to his home in Ithaca. “I have to make choices that will ultimately lead to fulfillment of my goals, no matter the consequences of that choice.”

The Odyssey continued to resonate with four 2003 graduates profiled in Lafayette Magazine in 2010. Matt Parrott, now an attorney, said he contemplated Odysseus’ many trials by fire during his turbulent first year in law school. Jacobi Cunningham, now a research scientist, claimed that his odyssey mantra—“expect the unexpected”—steadied him while adjusting to a new town and while analyzing unpredictable stresses from the recreational drug Ecstasy.

On other campuses across the country the common reading assignment is strictly an orientation exercise. At Lafayette it has long been the springboard for a year-long examination of the book’s themes and an introduction to the College’s intellectual community. The Odyssey, for example, was followed by an arts festival of Homeric events. The Sixth Extinction was matched with an exhibition tracing the extermination of the passenger pigeon that also served as the set for a performance of Song of Extinction by E.M. Lewis, and a visit to campus by the Pulitzer Prize-winning author herself.

In 2008, students read Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals. The theme of environmental sustainability was illustrated by a crop of corn grown on the Quad, then harvested and celebrated with special ceremony.

An entire academic ecosystem surrounded the 2005 choice, Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers, a graphic diary of the artist’s complex responses to the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the U.S. government’s complicated retaliations. First-year students watched a Lafayette-produced documentary with 60 interviewees, including Spiegelman. They participated in the birth of resident artist Sekou Sundiata’s “The America Project: The 51st (Dream) State,” a panoramic view of post-9/11 freedom of expression. They also had the opportunity to meet with Spiegelman when he visited campus.

The hottest debates unfolded on Web forums for five hot-button topics. More than 120 comments accompanied Spiegelman’s cartoon of former Vice President Dick Cheney cutting the throat of a flying eagle that wonders “Why Do They Hate Us? Why???” A particularly slippery reaction was submitted by Student I: “I myself find the image offensive simply because it holds so much truth about our country that I bribe myself to ignore on a daily basis.”

All this difficult discourse pleased Gladstone “Fluney” Hutchinson, dean of studies from 2001 to 2006 and an agent of Lafayette’s participation in “Imagining America,” a national consortium of public scholarship. “Students got a sense of, wow, I have the right to criticize, and even curse, my country, and it’s OK—I’m still here,” says the associate professor of economics. “They discovered that disruption can lead to new energy, and that it’s important to build new bridges so that people can’t exit the conversation.”

Through The Years

-

1992

-

1993

-

1994

-

1995

-

1996

-

1997

-

1998

-

1999,2000

-

2001

-

2002

-

2003

-

2004

-

2005

-

2006

-

2007

-

2008

-

2009

-

2010

-

2011

-

2012

-

2013

-

2014

-

2015

The Power Of Ideas

Hutchinson’s public scholarship was changed “substantially” by common-reading projects he supervised. He’s applied Lafayette lessons and methods to economic development programs in Honduras, New Orleans, and Appalachia. “We’re emphasizing face-to-face civic discourse,” he says, “assigning a person to hear what’s not being said, giving everyone an opportunity to put their identity on the table.”

Common books have changed other attitudes and latitudes. Pat Barker’s Regeneration, a novel concerning shell-shocked World War I soldiers in a hospital, helped Lauren Berry ’14 better understand the traumas of military friends who served in Middle Eastern wars. This new sympathy helped the psychology major during her First-Year Seminar, On Death and Dying, and her friendship with mentor John Colatch, Lafayette’s former chaplain. After graduating, she served as a fellow in the College’s Connected Communities program, helping launch the PARDner program of online peer advice for incoming first-year students. She’s spending her summer preparing to pursue a master’s degree in education.

Growing up in Jamaica, Stacey-Ann Yanique Pearson ’15 knew little of American racism. She knew much more after reading and discussing Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, a chronicle of an African American family unable to afford health insurance despite the fact that their late matriarch, a poor tobacco farmer, provided cells that helped develop everything from the polio vaccine to in-vitro fertilization. The book empowered Pearson to become intimately involved in discussing “the intricate nexus” of prejudice and politics. The civil and environmental engineering major has led programs as a resident adviser, a camp counselor for low-income students, and a volunteer for the Gender and Sexuality Resource Center.

Last year a program was initiated to make the summer assignment more colorful and more vital. Professors from each of the academic divisions dissected topics related to The Sixth Extinction in 10-12 minute presentations. “We wanted the talks to be short and sweet and just slightly out of the students’ comfort zone,” says Erica D’Agostino ’95, dean of advising and co-curricular programs, who started at Lafayette a year before the common book debuted. “We wanted to keep their minds moving to keep them from getting bored, to make them feel more embedded.”

The talks demonstrated how the book could be seen from different disciplines and set the stage for later discussion in First-Year Seminars.

Carolynn Van Dyke, now March Professor Emerita of English, started her talk with a video of James Dickey reading his poem “For the Last Wolverine.” She ended by suggesting that humanities and science teachers will help first-year students learn about things that Dickey believed won’t “die out.”

Focusing on energy and environmental issues in Texas, William Hornfeck, now professor emeritus of electrical and computer engineering, discussed the rise of fracking, the high-pressure removal of oil and natural gas from slate with water and chemicals, and the fall of the water level in Buchanan Lake, a reservoir that borders his home.

Hornfeck’s report made a big impact on McNamara, who as a Californian is well-aware of the threat of earthquakes, mudslides, and other natural disasters.

In his First-Year Seminar, the government and law major discovered how fossil fuels are harming rainforests, coral reefs, and other crucial habitats. For a research essay on fracking he interviewed his grandfather, who refused to allow an oil company to drill his Pennsylvania land, fearing damage from noise, pollution, and disease.

Hornfeck’s vigorous explanation of energy issues impressed Jeffrey Eric Finegan II ’16, who transferred last year from Bucknell University. “He made me think, hey, wait a minute, there must be a more efficient, better way of producing energy that’s also more diverse and inclusive,” says the major in German and government & law. “He told us that we should think about the environment in different ways, think about the bigger picture, try to reach an equilibrium in our understanding.”

Editors of the common-book experience want to reach equilibrium too. D’Agostino would like a more coordinated, yearlong program. McLoughlin would like to provide students more personal time with authors. Their quest will continue in August when first-year students gather to discuss Steven Johnson’s The Ghost Map, a sprawling history of the catastrophic effect and ingenious end of the cholera epidemic in 19th-century London. It’s an uncommon combination of science, religion, urban development, economics, engineering, sociology, and detective novel — a cosmos between covers