The Power of Nudge

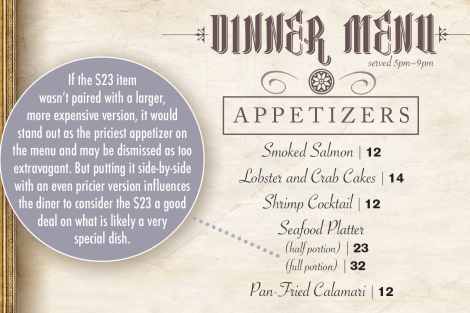

You’re out to eat and scanning the menu. You see a $55 seafood appetizer. Wow. Pretty outrageous, you think. That is until your eye catches the next item on the menu: a $109 seafood appetizer. Suddenly, by virtue of comparison, the $55 dish seems far more reasonable than it did just seconds earlier. Moreover, the least expensive appetizer on the menu, an $18 plate, now seems cheap (and inferior) by comparison.

None of this is an accident, says Joaquín Gómez-Miñambres, assistant professor of economics. Menus and wine lists alike can be strategically engineered to push you toward a particular dish or bottle, he says. In fact, folks at the Philadelphia restaurant where these are menu items may never intend for anyone to actually order the $109 Grand Plateau. The exorbitant dish could be a so-called “decoy,” simply there to shape customers’ perceptions of what’s reasonably priced, and as a result generate more interest in the $55 Cold Shellfish Platter.

Behavioral economists call this “nudging.” It’s a technique used to guide consumer behavior and influence decision making. The term was coined by Richard Thaler, who won the 2017 Nobel Prize in economics for his pioneering work in the nascent field of behavioral economics. Thaler’s celebrated book, Nudge, explores how businesses, organizations, and policymakers can be “choice architects” by creating cues and presenting options in a framework that directs people toward certain behaviors.

These nudges can direct people to adopt positive habits, like quitting smoking or saving energy. Or they can help a corporation bolster its bottom line by steering a customer toward a pricier running shoe, travel package, or restaurant dish.

Acknowledging humans are complicated beings influenced by psychological, social, and emotional factors seems like a fairly straightforward and benign concept. But until recently, it was considered heresy to contradict longstanding and deeply rooted economic theory that contends humans act in a logical fashion for their own best interest. Only in the past two decades has the revolutionary behavioral school of thought become more acceptable, says Gómez-Miñambres.

Joaquín Gómez-Miñambres

“Part of the reason that behavioral economics is becoming more mainstream is there is an understanding that the standard model of rational behavior doesn’t always accurately predict behavior,” he says. “The old economic models are based on a paradigm of rational, selfish behavior, which is obviously not what happens in the real world. Your behavior can change and adapt to different environments.”

Exploring and expanding this burgeoning field is Gómez-Miñambres’ academic focus and goal at Lafayette, where this past fall he became the College’s first behavioral economist. Gómez-Miñambres’ primary expertise is workplace motivation. He has done extensive research on the impact of monetary and non-monetary rewards, and he has studied the power of intrinsic rewards and how goal setting is increasingly important in modern-day workplaces.

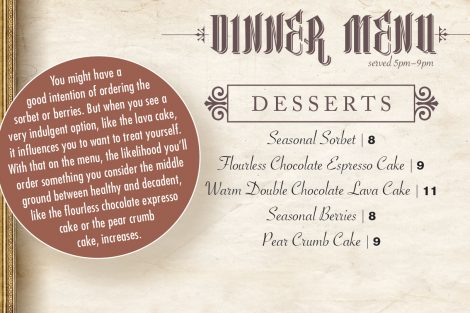

However, he says, one of the things that first sparked his interest in behavioral economics as a Ph.D. student at Universidad Carlos II de Madrid in Spain was how temptation can overrule logic and reason at restaurants.

“Suppose you are going to a restaurant, and you plan in advance to order a modest dessert,” he says. “If there is a really decadent, super-unhealthy item on the menu, it’s likely to influence you to change your mind. There is an increase in probability that you’ll go with something that is healthier than that decadent item, but that’s more of a splurge than what you had originally planned to order. You’ll make a compromise between what you want and what you should have, which doesn’t make economic sense. It’s not a rational point of view. And that is revealing—and interesting.”

Because restaurant menus are prime real estate for nudging tactics, we asked Gómez-Miñambres to reveal some tricks of the trade.

Tricks of the Trade

How restauranteurs engineer menus to influence your selections.

Keep it Short and Sweet

![]() Too many options can make people feel overwhelmed and stressed about making a decision. Keeping a menu simple and limited to a few select options helps people feel confident that they are making a sound decision when ordering.

Too many options can make people feel overwhelmed and stressed about making a decision. Keeping a menu simple and limited to a few select options helps people feel confident that they are making a sound decision when ordering.

Round Up

![]() Not including cents sends a message that the dish and the restaurant are higher quality. Having prices that end in 99 cents is the oldest trick in the book to signal a deal. While that tactic might still be used at fast-food restaurants, it’s unlikely you’ll see it at a restaurant that wants to establish a reputation for excellence.

Not including cents sends a message that the dish and the restaurant are higher quality. Having prices that end in 99 cents is the oldest trick in the book to signal a deal. While that tactic might still be used at fast-food restaurants, it’s unlikely you’ll see it at a restaurant that wants to establish a reputation for excellence.

Forget the $

![]() Research shows that removing currency symbols influences diners to spend more. Having a dollar sign before a 40 reinforces the idea that you are spending real money. Dropping it breaks that connection.

Research shows that removing currency symbols influences diners to spend more. Having a dollar sign before a 40 reinforces the idea that you are spending real money. Dropping it breaks that connection.

But will having a better understanding of these cues help you resist temptation? Gómez-Miñambres doesn’t think so.

“I know that pizza isn’t the healthiest choice, but when I’m tempted by pizza, I yield to the temptation. In the end, I’m just an irrational human being.”