Class Warfare

Two weeks earlier, a pair of freshmen wielding baseball bats had defended themselves against sophomores attempting to break into their room in South College. One of the sophomores was seriously injured. The melee had temporarily put a damper on Lafayette’s time-honored hazing war between sophomores and freshmen, but by this night, sophomores were back to breaking into the rooms of underclassmen and picking fights.

In East Hall, they stopped at a door of one of the “freshies” and knocked. No answer. They burst in the door.

Inside they found Stephen Crane, the man who in a few years would write some of the era’s most well-regarded works of fiction.

“… the figure of Crane backed into a corner with a revolver in hand,” Col. Ernest G. Smith 1894, a classmate of Crane’s, wrote of the incident in the Lafayette Alumnus in 1932. “He was ghastly white … and extremely nervous. There was no time to escape what might have proved a real tragedy until Crane unexpectedly seemed to wilt limply in place and the loaded revolver dropped harmlessly to the floor.”

During the gilded age, the civil war between Lafayette’s freshmen and sophomores might have been good- natured, but it had become a problem. It existed at a nexus of violence and tradition, and while administrators seemed unable to stop both forces, they sought to control them by sanctioning some of the hazing traditions and swapping others for less vicious pursuits.

So, for decades in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Lafayette’s first- and second-years pelted one another with bags of flour, wrote horrible things about one another on posters, and battled over a piece of wood.

All in the name of brotherly love.

Poster Night

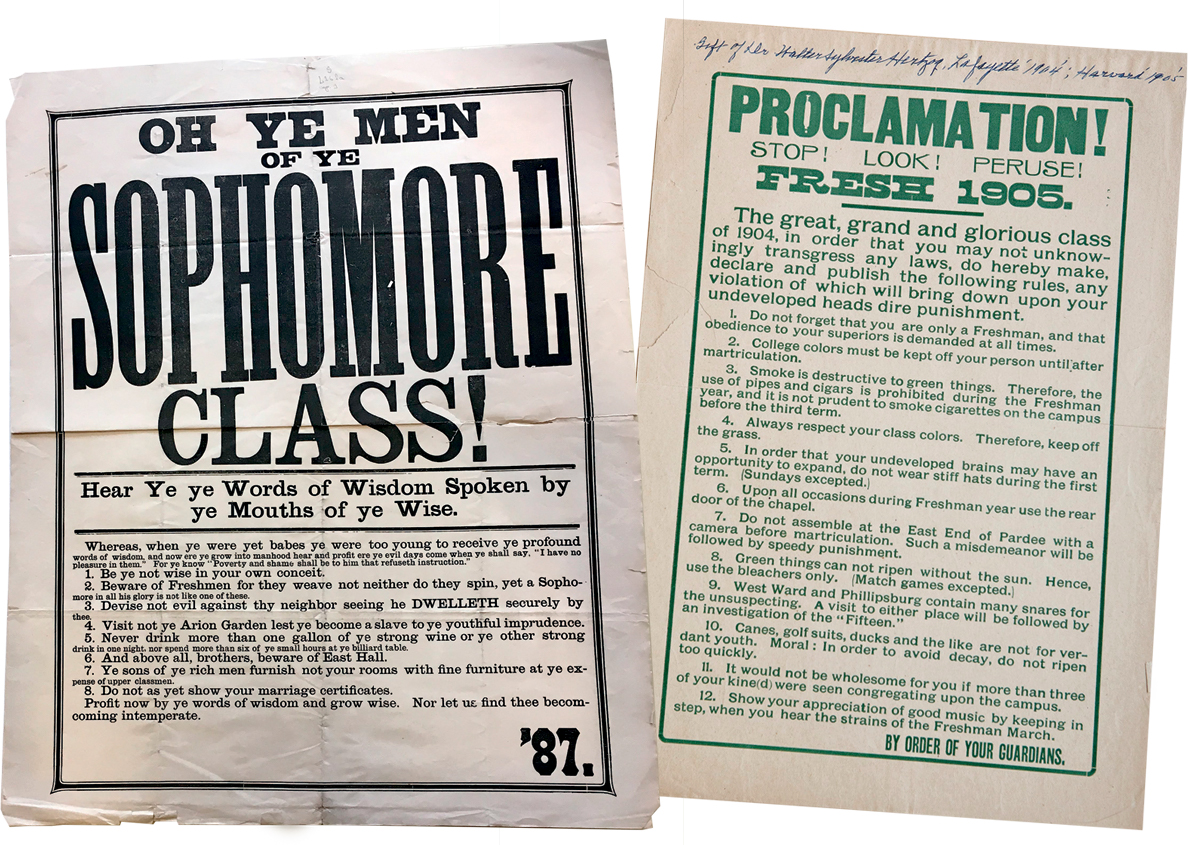

In winter freshmen and sophomores printed posters poking fun at each other. Think cyberbullying minus the cyber. Sophomores taunted freshmen for their “undeveloped brains,” “flaxen curls and eyes of heavenly blue,” and other insults such as … well … many can’t be printed here. Late at night, they covered Easton with their posters. According to The Biography of a College, the night “had often fallen into disrepute by reason of the scurrilous and sometimes profane and obscene epithets used in the poster itself.”

The 1899 posters were particularly egregious, according to an article in the Feb. 17, 1899, edition of The Lafayette.

“There is nothing witty about them, but the wealth of expression and breath [sic] of vocabulary displayed by the authors, would excite the envy of the lowest inhabitant of the slums of one of our great cities,” read the article.

Nevertheless, the College allowed it to go on.

Cane Rushes

Cane of unknown vintage used in a cane rush

The cane rush was suggested by legendary English Professor Francis March. Both the first- and second-year classes faced one another. In front of each crowd stood two large men, one from each class, each holding “a stout stick about six feet long.” At the sound of a gun, each class fought for 10 minutes to control the stick. A common ruse was to call “man hurt” in hopes opponents would draw back from

the scrimmage.

At the end, class supervisors counted the hands on the stick. Whichever class had the most hands won the cane rush.

Banner Scraps

In an angle of a building, a red flag was suspended about 10 or 12 feet off the ground. Freshmen massed in front of the flag. Sophomores came armed with paper bags full of white Pillsbury Best flour, and sometimes buckets of water, which they hurled at the younger Leopards after someone fired a starting gun.

Sophomores then formed a wedge and tried to push over the dust-blinded younger men to reach the flag. “The flag could not be reached without standing on the heads or shoulders of Freshmen,” according to The Biography of a College.

While much about some of the traditions seems lost to history, The Lafayette student newspaper provided detailed descriptions of some of the brawls, including the one below published in the Oct. 3, 1911, issue.

William Dannehower ’12, captain of the Leopard football team, fired a pistol to start the competition.

“Every second witnessed a noble-chested form lifted bodily and cast upon the heads of those nervy Frosh,” the story read. “But the noble-chested form also soon sank among dozens of grasping hands.”

During the battle, the first-years roared their “class yell as a token of defiance in the thick of the fight.”

After minutes passed, Dannehower fired the gun again. Twelve feet above the white-dusted battlefield, pushed into a corner of the Star Barn, now the site of Markle Hall, a red scrap of cloth caught the breeze.

The first-years, covered head to toe in white baking flour as if they’d just won a culinary competition, then headed off to class, victorious in the 1911 banner scrap.

More on Stephen Crane

Crane, renowned late 19th- and early 20th-century author of The Red Badge of Courage and The Open Boat, enrolled at Lafayette as a member of the Class of 1894. Despite his previously described encounter with hazing, Crane appeared to take pride in another event. He stood and defended the freshmen flag during that fall’s banner scrap. In a letter to a high school friend he wrote (complete with his own spelling and punctuation errors): “I send you a piece of the banner we took away from the Sophemores last week. It dont look like much does it? But just remember, I got a black and blue nose, a barked shin, skin off my hands and a lame shoulder, in the row you can appreciate it. So keep it, and when you look at it think of me scraping about twice a week over some old rag that says ‘Fresh 94’ on it.”

Crane, renowned late 19th- and early 20th-century author of The Red Badge of Courage and The Open Boat, enrolled at Lafayette as a member of the Class of 1894. Despite his previously described encounter with hazing, Crane appeared to take pride in another event. He stood and defended the freshmen flag during that fall’s banner scrap. In a letter to a high school friend he wrote (complete with his own spelling and punctuation errors): “I send you a piece of the banner we took away from the Sophemores last week. It dont look like much does it? But just remember, I got a black and blue nose, a barked shin, skin off my hands and a lame shoulder, in the row you can appreciate it. So keep it, and when you look at it think of me scraping about twice a week over some old rag that says ‘Fresh 94’ on it.”