Reimagining Public Housing in Easton

Tucked away off bustling Northampton Street in Easton’s West Ward, the Union Street Public Housing Project is easily missed, yet the people who live there yearn to be heard and hope for change.

Students in Prof. Mary Wilford-Hunt’s Sustainable Solutions (EGRS 480.02) course spent the spring semester learning about the 1960s-era public housing project, listening to the desires of residents, and applying their imaginations to envision a brighter future that integrates the community with the city.

It was an immersive experience, bringing students face-to-face with residents who described their wishes and needs for their neighborhood.

Urban planning experts and other professionals accompanied their journey, guiding and inspiring the students as they set out on their designs for Reimagining the Union Street Public Housing Project.

Among them was state Rep. Robert Freeman, who represents Easton and grew up in the West Ward.

On one of his visits with students, he shared his memories of growing up in the West Ward, the city’s most populous neighborhood. As students leaned in with interest, he recounted the joys of playing in the seemingly endless maze of West Ward’s alleys, walking from 10th Street to a five and dime store downtown, and a strong, tightly woven sense of place and stability created by multiple neighborhood elementary schools.

With his interests in history and urban planning, Freeman expressed his hopes for returning light industrial businesses to the West Ward and attracting affordable mixed housing with public cafes, community gathering places, and more grocery stores.

“The importance of good design has been lost in this country,” Freeman said, lamenting how urban renewal architecture developed after World War II wasn’t always compatible with a community’s historic character. He cited a quote from Winston Churchill, “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.”

Freeman said that the future of the West Ward, once a blue-collar working class neighborhood, is bright, grounded in the overall rediscovery of Easton as a safe and comfortable destination for families and visitors.

The timing of the Union Street course also aligned with a recent $450,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Choice Neighborhoods program.

Awarded to the Greater Easton Development Partnership and Easton’s Housing Authority, the grant will help create a lasting impact on the West Ward by empowering the 140 Union Street residents to document their perspectives on housing, education, health, child care, public safety, employment, and other socio-economic issues. After a protracted period of disinvestment, pessimism, and crime, the North Union Street neighborhood has tremendous momentum toward positive change, according to the grant award.

Over two years, the HUD grant will support community planning and foster a collaborative relationship with residents to identify goals around housing and quality of life issues, said Jared Mast ’04, executive director of Greater Easton Development Partnership, a nonprofit organization that’s dedicated to nurturing Easton’s economic well-being and cultural vibrancy. Once the initial plan is completed, it moves into an implementation phase in which competitive grants would be pursued with the goal of rehabilitating Union Street and its neighboring areas.

The neighborhood could be recast to create mixed income housing, add more housing units, and end Union Street’s isolation from the rest of the West Ward, Mast said.

Integrating and connecting the non-street-facing neighborhood back into the greater Easton community will help meet the shared goals of the city and the Greater Easton Development Partnership to increase affordable housing in the West Ward, he said.

Mast said the creative work done over the spring by Wilford-Hunt’s students, such as identifying green space and recreational assets in the Union Street housing complex, is a “perfect fit” in helping attain those goals.

“People who live in an urban environment should also have access to these kinds of resources,” he said.

Final presentations

It’s never easy to make a formal presentation, even in front of friends and peers. Add a room full of professionals who know every detail of the subject matter you’re presenting, and the jitter quotient can rise exponentially.

Poised and prepared, the students, who worked in pairs, made their juried-style presentations before a group of experts and community leaders eager to hear and see what the students envision for North Union Street.

Steven Stilianos ’22 presenting Sophie Saldivar ’21 and his plan for the Union Street Public Housing Project

Each with their own personality and rhythm, the five detailed plans offered improved public transportation access, water features, underground parking, taking advantage of the sloping topography, private balconies, playgrounds, terraced apartments, pedestrian paths, solar panels, bike paths, retail space, more street lighting and green space, and realignment of streets to pull Union Street out of its isolation.

“Sometimes public housing gets a bad rap,” said Steven Stilianos ’22 whose presentation with Sophie Saldivar ’21 included pedestrian access to the Karl Stirner Arts Trail and other points of interest, a community garden, and a welcoming archway. “We want the residents to be proud of their neighborhood.”

In their vision for Dutchtown Villages, a mixed-use with retail plan, Austin Goldstein ’21 and Nicole Holzapfel ’21 tapped into their conversations with residents to develop green space and more access to fresh food.

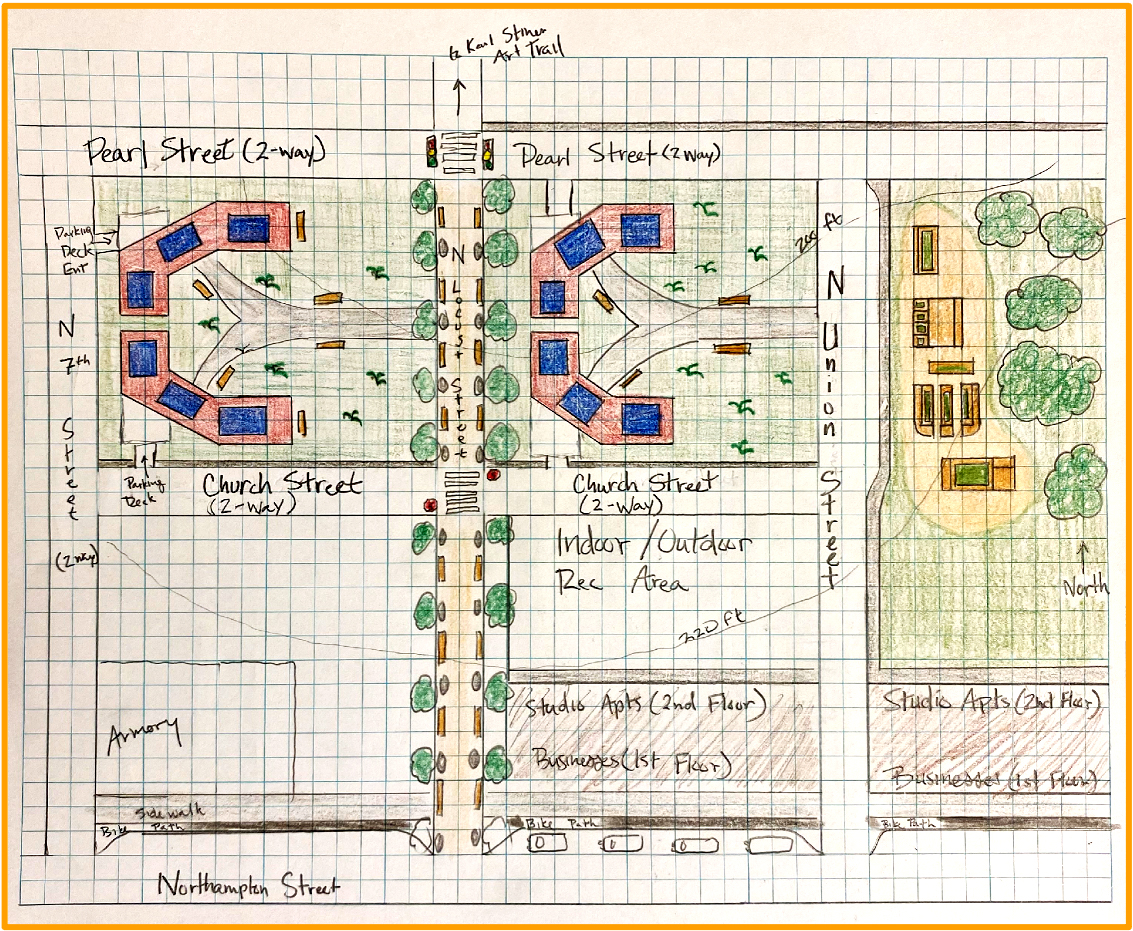

Jerri Norman ’22 warmly dubbed her presentation “No Place Like Home” for her Pearl Street Commons design, which incorporated more personal and community space for residents, including a North Locust Street pedestrian way, green space on North Union Street, and mixed income living spaces with private and semi-private bathrooms and private balconies. Her goal, reflected in her hand-drawn sketches on grid paper, was providing comfort and solace.

Jerri Norman ’22 plans for green space in her Pearl Street Commons design

Clearly impressed by her students’ work, Wilford-Hunt reminded them that their concepts might eventually find their way into the planning supported by the HUD grant.

Michael Handzo ’11, project coordinator for Lehigh Valley Community Land Trust, appreciated how the students reflected human needs in their concepts, while others in attendance acknowledged the practicality of the designs and noted that they’d make it through municipal and regulatory approvals.

Equally delighted, Freeman said he enjoyed the opportunity to speak to Wilford-Hunt’s class about students’ project proposals for the North Union Street public housing site and to be able to give them some historical context on the impact of urban renewal on that site in the 1970s.

“I was very impressed with the students in the class. They are a very bright group of students who took a keen interest in the assignment and were very engaged in the topic overall,” he said.

“They offered imaginative and thought-provoking proposals. Some of the students made a real effort to draw on the historical context of the neighborhood and to seek to reestablish the grid street plan that was once there,” Freeman added. “All of them offered very vivid proposals of what the site could be transformed into and gave careful thought to the needs of the residents as well as the aesthetics of the setting with an emphasis on green space.”