Let’s Amplify This Incredible Place

Nicole Hurd knows exactly when she found her voice. She was a fifth-grader at Corpus Christi Elementary School in Los Angeles. Like many at that age, she was a bit shy and introverted, a bit awkward. But her teacher, Ms. Whitman, had thrown an assignment at the class. It was 1980, in the midst of a presidential race among Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and (running as an independent, in a campaign managed by a Lafayette graduate) John Anderson. Every student was assigned to take on the persona of one of the candidates. Hurd was to be Reagan.

She carried out the assignment; she carried it out with force. In the end, her 30 or so classmates, even the Jimmy Carter stand-in, voted for her. There was just one dissenting vote. She lost track of that boy.

“It was the best feeling in the world,” Hurd, named in May as Lafayette’s 18th president, says today. “For the first time in my life, I had really used my voice. I said to myself, this is interesting and fun. People are reacting to me in a way I want them to be reacting. The teacher gets full credit for it. That’s the beauty of being an educator. Some of the seeds you plant get to blossom on your watch.”

Talking about the work that would later absorb and define her, she deploys a related metaphor: nurturing the spark that ignites fireworks. That could be the credo of the College Advising Corps, the nation’s largest college access program. She conceived it as a pilot program in 2005 at University of Virginia (UVA), where she was leading the Center for Undergraduate Excellence and the Office of Undergraduate Research. Over the years, the corps has helped more than 525,000 low-income, first-generation, and underrepresented students enroll in higher education. That work is accomplished with more than 800 recent college graduates, selected to serve as near-peer advisers in high schools. Hurd refers to the program’s double impact: It nurtures the pipeline for entering college, and it helps create a cadre of professionals who see themselves as agents of change.

Hurd’s appointment was announced before an audience of board members, faculty, staff, and students May 19 in Farinon College Center.

Hurd talks a lot about passion and systems: having enthusiasm for the task, and also doing the detailed work to make it happen. She sees that dual quality expressed in the character of Lafayette, in its combination of the liberal arts and engineering.

Peter Grauer, founding board chair of the College Advising Corps and chairman of Bloomberg L.P., sees passion and systems as features of Hurd’s career. Grauer, who has an array of civic involvements, mentions watching Hurd connect with an audience of 1,000 or so of her college advisers at their conference in Boston. “She can command people’s attention, and not everybody who is lucky enough to have a position of responsibility is equipped with that ability to call people to the moment, to inspire people, and to enable them to do things they wouldn’t normally ask of themselves. She makes advisers feel like they’re the most important people in the world. One of the characteristics of leadership is emotional intelligence. She has that. She is empathetic and is intensely authentic; there is nothing superficial about her in the way she conducts herself. She is passionate about whatever she does.”

And for all of her entrepreneurial energy, Grauer adds, Hurd has “the skills to run a large organization,” including “the courage to have difficult conversations and to do difficult things.” Hurd has shown the discipline to keep the corps focused on its founding mission around college access—“building the platform with excellence,” as he puts it, rather than succumbing to mission creep.

Hurd was introduced on campus by Robert Sell ’84, chair of the Board of Trustees and of the presidential search committee. He ran through a range of her traits, from intellectual curiosity to an ability to work with different constituencies. She has the capacity to keep Lafayette advancing, Sell said. He pointed to her standing as a leader in higher education, and to her ties across the higher-education landscape. One of her recommenders, he told the audience, identified another duality in Hurd: a pastoral manner along with a can-do chutzpah.

Whether it reflects a pastoral manner or pure determination, there’s a lot to another of Hurd’s oft-cited phrases: “I believe in you.” At first it was a family mantra, thanks to her husband, Bill Hurd, whom she met while she was in a master’s program at Georgetown. Later, while studying for her Ph.D. in religious studies at UVA, Hurd was getting ready to take her comprehensive exams. It’s always a grueling process; she had a lot of understandable anxiety. Bill, doing his best imitation of one of the slick characters in Jerry Maguire (the movie was a recent sensation), threw out the line: “I believe in you.” “He knew what I needed to hear to be unstuck,” Hurd recalls. “Bill uses it all the time. I can’t remember a board meeting, a fundraising pitch, where Bill hasn’t texted me beforehand with that line.”

Sure enough, as she was heading into her finalist interview for the Lafayette presidency, Bill embedded a picture in a text message. It showed their kitchen whiteboard. Scrawled on it were expressions of love and support from him and their two children. And, inevitably, “I believe in you.”

Hurd is the daughter of first-generation college graduates (she’s the oldest of three children). Her mother went to college as an engineering student; back in the 1960s, she found so little support for women in the field that she switched out of engineering. Her father was pushed to think about college by a longtime mentor, who dropped him off as he started at Notre Dame. As she was considering colleges, Hurd approached her school counselor with the expected list of “safety schools,” “reaches,” and some in the middle. Then the counselor looked over her list and informed her, “There’s one school you’re not going to get into,” she recalls, “and that’s Notre Dame.”

Hurd attended the White House College Opportunity Summit in January 2014. President Obama hosted college presidents and other leaders at an event focused on expanding opportunity for students.

“When you tell me I can’t do something that I’m confident I can do, I’ll just go and do it,” Hurd says. “If you tell me something’s not possible, just watch me.” She became “obsessed” with Notre Dame and she wrote a letter to the admissions dean, outlining how her curriculum made her a perfect fit. She got in.

One of the characteristics of leadership is emotional intelligence. Nicole has that. She is empathetic and is intensely authentic; there is nothing superficial about her in the way she conducts herself.

–Peter Grauer,

founding board chair of the College Advising Corps

and chairman of Bloomberg L.P.

At Notre Dame, she ran for student government president. Her running mate for the position of vice president, Eric Griggs, now a well-known community physician in New Orleans, is African American. Busy completing his pre-med requirements, he initially resisted the idea, but Hurd wore him down. The combined ticket was a first for Notre Dame, with Hurd as the first female student in the running for president. The other candidates were all white men.

Part of her platform was strengthening advising; she envisioned a “Students Helping Students” program. As she described it for a student magazine, Scholastic, someone studying in the business school, for example, would advise an undergraduate about financial literacy. According to Griggs, Hurd’s overall goal was to ensure that, at a largely homogenous institution, every voice would be honored, that the interests of students from all backgrounds would be respected. The ticket lost in a runoff by a small margin, some 150 votes.

Geraldine Ferraro, the first woman to run for vice president on a major-party ticket, gave a talk on campus, saw the campaign posters, and reached out to Hurd. Ferraro offered congratulations and told Hurd never to give up on her ambitions. The numbers just weren’t on her side: At that point, women made up just a small percentage of Notre Dame’s student body—though on campus, as the student paper, The Observer, reported, this was “The Year of Women.” In the same paper, Hurd noted that her pride in the campaign was tempered by harassing messages that targeted her and her running mate. “I believe this university has great strides to make in terms of cultural diversity,” she wrote.

Griggs, who remains a close friend, says the experience had a lasting impact on Hurd. “It made her stronger. It deepened her resolve to lead, to do the right thing, to make a difference.”

Hurd found she could make a difference through teaching. At University of Virginia, she taught a course on female saints. “There is equal rigor and value in both the writings of Thomas Aquinas and Catherine of Siena,” she once told an interviewer. (In the past academic year, she remotely taught a UVA class on educational leadership and social change; she drew in “an all-star group of social-change leaders” as guest speakers, many of them on the board of the College Advising Corps.) She says: “I value the research piece. I value the life of the mind, and I love spending time in a good library.” For all the rewards of research, engaging with students, certainly in the classroom, but also by helping them land international fellowships—that, for her, was what it was all about. Making sparks into fireworks.

What she’s excited about with Lafayette turns out to be what makes her so well-suited for the job. She wants to see the entire institution at work, and from there she wants to benefit the entire institution—the philosophy department, the food service, the physical plant, the women’s lacrosse team, and on and on.

–Edward Ayers,

former dean of arts and sciences at University of Virginia

Her dissertation was reflected in her teaching; it was titled “The Master Art of a Saint: Katharine Drexel and Her Theology of Education.” An undergraduate history major, she had long been interested in the intersection of history, religion, and race. Brought up in Philadelphia, in privileged circumstances, Drexel (1858-1955), only the second American-born saint, founded the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. As Hurd wrote, she had “a tremendous impact on the lives of thousands of African Americans and Native Americans.” The impact extended to the founding of Xavier University in New Orleans and over 200 schools, including a chain of schools in rural Louisiana. Hurd spent time in different archival collections, consulting everything from school records to travel diaries. She also attended the 2000 canonization ceremony, in Rome’s St. Peter’s Square.

Given her later trajectory, it’s easy to read into the dissertation why Hurd was drawn to her subject. Drexel “gave a lot more than money and buildings;” a “generous spirit,” she also “gave herself.” Her life “incorporated all people,” and “she chose to share this grace by educating those who had been marginalized.” When informed of the decision of the Catholic University to award her an honorary degree—the first woman to be so honored—Drexel declined to participate in person but wrote an acceptance that, in Hurd’s words, “showed the underlying spirit of all of Katharine’s actions—humility.”

“People talk about what a grind it is to do a dissertation. My dissertation was actually inspiring. She was a very multifaceted woman, and she hasn’t been given the credit she deserves. I wanted to amplify her voice. Her humility, her grace—how could you not fall in love with this woman?” She adds: “Of course, she also had tenacity and guts.”

In 2005, The Chronicle of Higher Education ran an opinion piece that framed the case for what would become the College Advising Corps. It was co-written by Edward Ayers, at the time dean of arts and sciences at UVA, and Hurd, then in her administrative role. Hurd had attended a meeting in Charlottesville where the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation presented some sobering data: a student-to-counselor ratio of 369:1; just 53% of Virginians entering college directly from high school. The Chronicle piece, focusing on the mission of flagship universities, argued that higher education should be seen as “the path to a brighter future” and as “within reach” for students, regardless of economic circumstances.

Hurd had identified a mission. With the support of the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, she would lead what was initially called the College Guide program.

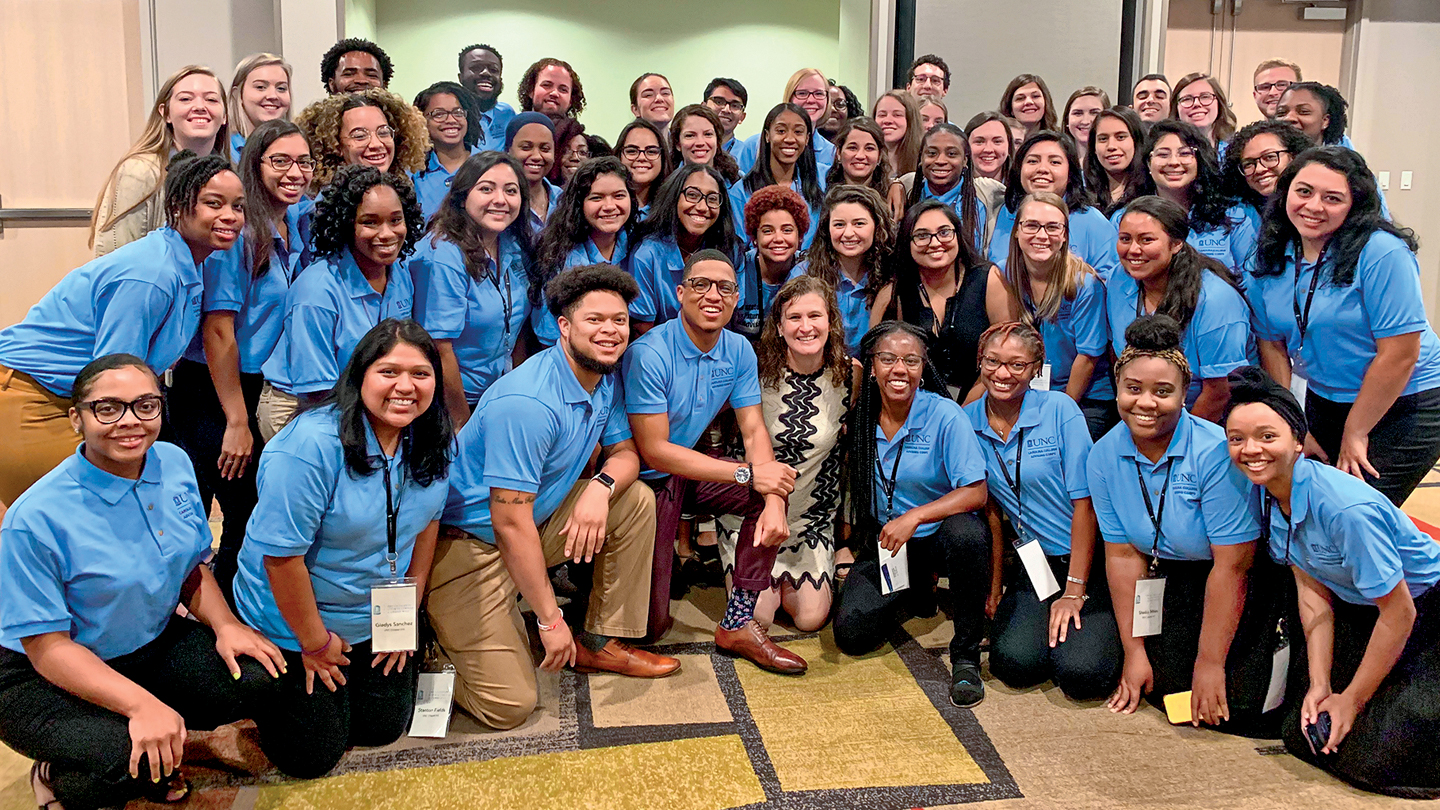

Hurd with College Advising Corps’ advisors at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

A small group of “public-service-minded new graduates” from UVA would be trained “to advise students on applying to college” and placed in underserved areas throughout the state. Ayers, later president of University of Richmond, credits Hurd not just with wanting to address the need of improving college access, but also with recognizing the value of recruiting recent graduates. The program embraced the spirit of a social-good organization like Teach For America, he says. It channeled that spirit particularly effectively for a fresh-out-of-of college cohort. “This would be a great thing for accomplished young people who were really eager to give back to society. Twenty-two-year-olds are in the beginning of their careers. What they do know about is getting into college and going to college. There, they have the experiential knowledge.”

In 2006, the foundation provided another hefty grant to expand the program. That move surprised Hurd, The Chronicle reported, noting that the corps had established itself “just as college access has been getting more attention.” In turn, she offered to quit her day job to run the program full time—surprising the foundation.

With Hurd as its head, the College Advising Corps moved its headquarters to University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC), where it would be “incubated.” After about six years, it became a stand-alone nonprofit. “Some of us were very worried,” recalls Holden Thorp, then-chancellor of UNC. “It required her to go out and form partnerships all around the country with different universities, to really ramp up the fundraising, to put aside the institutional support she enjoyed at UNC. A lot of people would have kept just rolling along with the program as it existed. But she has the ability to do hard things; she knows how to share her goals with others and get them excited about what she wants to do. She didn’t just keep the program going. She built it up significantly.”

As it has built up, the corps has been documenting its success. Much of the documentation comes from Stanford University and a professor in its School of Education, Eric Bettinger. “We’re increasingly in a world where accountability is key,” he says. He regularly surveys its students and tracks where they end up in college; he does parallel surveys to document the experiences of advisers. The corps is a learning culture, as he describes it. And so it’s adjusted its methods according to where the data lead—for example, placing more emphasis on adviser conversations with the parents, not just with the teachers, of aspiring college students.

“When you’re in meetings with Nicole,” Bettinger says, “you realize that she leads a culture in which she talks about grace and humility. As a quantitative researcher, I have to ask, what does that mean? Well, you’re showing humility when you look at data carefully, and you do that to figure out if you’re fulfilling your commitments in the most effective way. You’re sending the message throughout the organization, let’s learn, let’s understand ourselves better, let’s try to be better. It’s fun to work with that kind of organization.”

Bill and Nicole Hurd with children Matthew (will attend University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the fall) and Monica (will begin her sophomore year at University of Virginia). Not pictured: Sunshine and Sadie, the Hurd family’s golden retrievers.

The three places where Hurd picked up degrees—Notre Dame, Georgetown, and University of Virginia—are all research universities. But they also foster “intimate learning environments,” Hurd says. “They invest a lot in faculty-student relationships, and they take undergraduate life seriously.” In her view, Lafayette, with its strong student focus, is driven by the qualities that propelled her into the academy. And she considers Lafayette’s successful path through the pandemic—along with the countless messages of congratulations she’s received from all over the Lafayette universe—a strong statement of community-mindedness. As she got to know the members of the search committee, she came to see them as “amazing people who love an amazing place.”

Ayers, the onetime UVA dean, says of his former colleague: “What she’s excited about with Lafayette turns out to be what makes her so well-suited for the job. She wants to see the entire institution at work, and from there she wants to benefit the entire institution—the philosophy department, the food service, the physical plant, the women’s lacrosse team, and on and on. She will find all of that intellectually interesting. She will care not just about one aspect of the place. She will care about the whole community.”

Hurd acknowledges that it can be a complicated decision for an organization’s founder to step away. But she leaves the College Advising Corps with that organization in good shape. Now she’s focused on aligning herself with the passions and the systems distinctive to Lafayette, on celebrating and elevating the voices of Lafayette. For her, this personal transition is not a bittersweet moment. It feels like the perfect opportunity. “We have a diamond here,” she says. “Let’s have it shine to its full potential.”

Robert J. Bliwise ’76 is editor of Duke Magazine and has taught magazine journalism at Duke University.