United with Ukraine

When Ukraine was invaded in February, Lafayette College was, geographically, far from the dangers of war. But even though nearly 5,000 miles separate Easton from Eastern Europe, the tension still felt close to home.

Professors were concerned about colleagues and friends abroad. Ukrainian Americans kept tabs on the whereabouts of extended relatives: Is their city under attack? Are they sheltering in the mountain region? Were they displaced to a different country altogether? International students from Ukraine and Russia struggled with those same uncertainties of their families’ safety, but also their own—wondering when, or if, they’d be able to return back home.

However, as stress and fear mounted in the months after the invasion, so did the collective efforts to help from the Lafayette community. Here’s how students, faculty, and staff spent the spring semester banding together to support those impacted by the crisis—those far away as well as those on campus.

ACTIVISM THROUGH ART

Pedro Barbeito, assistant professor of art, was already a few weeks into his Beginning Printmaking class when he decided to change the direction of the syllabus. Printmaking, as an art form, has long been a way to send a message or spread ideas. Look no further than the signage used in protests or presidential campaigns. So when the Ukraine invasion happened, Barbeito thought this was an opportunity to let his class experience how art connects to a cause.

He tasked each of his students, who were mostly seniors, with creating a design that made a statement about the war in Ukraine. One idea was a dove flying out of a wheat field. Another sketch was of a sunflower—the country’s national flower—with a symbolic detail in each petal. They voted anonymously on their favorite design: “Peace for Ukraine,” in blue and yellow, by Alexandra Kasparian ’22. “Her design had a visual presence and a generosity to it,” says Barbeito. Students then produced it, by hand, on posters and T-shirts in the studio; soon, these copies would be sold around campus to directly support people in Ukraine.

Students were graded on not just their design and technical ability—but also their thoughtfulness. “There was a lot of dialogue,” says Barbeito. “And I think this is where printmaking can really enrich a student’s experience.” There were logistical details to figure out (i.e., pricing the items) and technical questions as well—this was an introductory class, after all. But the students also dug into deeper conversations about the conflict.

The merchandise they made—a few dozen T-shirts, plus 25 posters—quickly sold out; a pair of items was even donated to Skillman Library’s Special Collections of activism-related paraphernalia. Barbeito, who also serves as director of the Experimental Printmaking Institute, was so pleased with the response from students that he’s planning to incorporate other current events into future classes. “This far exceeded what I had envisioned,” Barbeito says.

DELIVERING AID OVERSEAS

Ukrainian American Deanna Hanchuk ’22 was initially shocked when she heard about the invasion. Hanchuk, who speaks Ukrainian at home, has relatives abroad and immediately wanted to help. “I’m an ocean away,” she says, “but I thought, ‘What can I do on campus?’”

So the chemical engineering major went to Student Government and pitched a three-week student fundraising campaign called “United with Ukraine.” All money would go to the nonprofit Razom; its emergency relief fund delivers necessities to people on the ground in Ukraine, from medical supplies and ambulances to equipment like walkie-talkies and drones. (Razom, which is Ukrainian for “together,” was founded in 2014 in response to border issues with Russia.) “They have the outreach and know the logistics to make sure the deliveries get there,” Hanchuk says.

To carry out the campaign, Hanchuk connected with the Russian and Eastern European Studies (REES) program and with student representatives from the International Students Association and Prof. Barbeito’s printmaking class. During the first week of raising money, there was a table in Farinon where passersby could make direct credit card donations to Razom. The following week, volunteers took to social media and organized a Venmo fundraiser.

And then, over a weekend in late April, Hanchuk set up shop on the Quad with two goals in mind: to raise money and remind everyone that there was still a war going on. (“Ukraine needs constant help and donations,” she explains.) Sitting there, she sold T-shirts and posters from the printmaking class; Ukrainian flag stickers donated from her church back home in New Jersey; powdered Ukrainian khrustyky cookies; and pierogies from a nearby Polish restaurant.

In total, “United with Ukraine” raised more than $2,000 for Razom in just a couple of weeks. “The Ukrainian community has always been strong,” Hanchuk says.

Associate professor of economics Olena Ogrokhina, who was raised in Kyiv and studied at the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE), contributed to the relief effort from campus. Ogrokhina led a collection of humanitarian aid, shipping nine large boxes full of medical supplies to Ukraine, and spoke at a fundraiser organized by Daniel Benedict, Lafayette’s rugby coach. Ogrokhina also encouraged the campus community to contribute to the KSE Foundation, which provides humanitarian relief such as food, transportation, refugee help, and first aid, and protects kids. The foundation has raised almost $25.5 million. “My hope for Ukraine is its continued independence and unfettered independence in the future,” she says. “The Ukrainian people possess standard Slavic toughness, and that is coupled with motivation powered by love. Love of family, freedom, and country.”

GETTING VOCAL

Joshua Sanborn, history professor and chair of the REES program, and his colleagues felt the tension looming between Ukraine and Russia for some time. In February, before the invasion, he and Katalin Fabian, professor of government and law, held a lecture, “Threats of War: Russia, Ukraine, and NATO in Crisis,” to outline the situation and share thoughts on the matter. But even as concern grew, the experts hoped that a full-scale invasion would be avoided. “It didn’t make a lot of political sense,” Sanborn says. “It still doesn’t make a lot of political sense—even from Russia’s perspective.”

History professor and chair of the REES program Joshua Sanborn created opportunities for impacted students to talk, learn, and support each other.

When Vladimir Putin launched the war, the REES program was trying to figure out how to respond to the news. Lindsay Ceballos, assistant professor of history and REES, suggested they organize a rally right away. “We needed to create a space for people to just talk about it,” Ceballos says. She borrowed a megaphone from a neighbor at home and began to get the word out on campus.

On March 1, more than 200 people gathered on the Quad for the rally. “This was a moment to show solidarity,” Sanborn says, “and to have people talk about their experiences and what the war was doing to their families and their communities.” Around 10-15 people addressed the crowd, including students with personal connections, like Reni Mokrii ’25, who is from Moscow but has family in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus. Faculty members were also in attendance—this is a very traumatic time for professionals who’ve invested their careers in these regions and still have friends and colleagues abroad. And there were plenty of students and staff without any close ties to the war, who, nevertheless, just wanted to show up and support.

REES kept the conversation going throughout the semester. Ceballos explains that her Russian history lessons in class were often connected to what’s going on in Ukraine: “Any aggressive movement made by Soviet power is difficult not to see in the context of today.” Meanwhile, Sanborn and his wife hosted a small dinner for students at his house with catered food from a local Ukrainian deli. He, Fabian, and Hafsa Kanjwal, assistant professor of history, also held a second roundtable discussion about the situation in March.

The issues being talked about aren’t only from Ukrainian perspectives. Students from Russia, says Sanborn, are deeply pained about what’s going on. Jessica Carr, associate professor of religious studies, adds that many students feel like victims of their government’s policies and are trying to work that out as well. “We have students from so many backgrounds who remain afraid and a lot of other emotions,” she says. “One’s nationality is not one’s ethnicity.”

Conversations about the crisis may be cathartic—they’re also critical to learning about the war and understanding others on campus. “One of the benefits of having a place with a strong global education is you have those experts here,” says Sanborn about Lafayette. “And it’s a part of our mission to share that expertise.”

CONNECTING WITH THE COMMUNITY

On a Sunday afternoon in May, 20 volunteers were ready to work at LaFarm, Lafayette’s farm located a few miles north of campus. Most of the group were affiliated with the College, but about a third were from around the Lehigh Valley, including two Eastern Orthodox priests and families from those Ukrainian congregations.

They were there to plant sunflower seeds. It was Josh Parr’s idea: He had just started at Lafayette in January as manager of food and farm and was inspired by the sunflower seed companies that were donating proceeds to Ukrainian relief. He wanted to partner with the local Ukrainian community, so he first reached out to nearby churches. Burpee Gardening then donated the seeds—around 3,000 in total—which was something Jamie Mattikow ’86, Burpee’s CEO and president, was proud to do: “We support Lafayette and the Lehigh Valley community coming together to help humanitarian efforts in Ukraine.”

After Parr welcomed everyone, the priests talked about the history and significance of the sunflower—a bloom that’s long represented peace and still drives Ukraine’s economy today. The volunteers started digging, and, once finished, the priests led a prayer of thanksgiving for the sunflowers and a plea for the war to end. “In times of great uncertainty and distress, it can be very grounding to return to something in nature like planting a seed,” Parr says. “These seeds will be sprouting and growing. It gives you something to hope for.”

Once the sunflowers begin to bloom in early August, Parr will host another event at LaFarm where the public can pick bouquets in exchange for a donation to help Ukraine. He’ll continue to raise money by selling them through their online store and at local farmers markets.

Parr says it was beautiful to see members of different communities, who might not otherwise know each other or interact, share this experience together. “For Lafayette to have an area that is equipped for any sort of project of planting and growing,” he says, “that opens up the possibilities of how we can reach out and engage with the community in the future.”

LOOKING OUT FOR THE LAFAYETTE FAMILY

“Our No. 1 priority is making sure that the students who are directly affected by the war are as OK as they can be,” Sanborn says. Faculty and staff have done what they can, and more, to support Lafayette’s international students on campus. This summer, they’ve helped students find campus jobs or research positions in case they weren’t going home. (Sanborn hired one student to stay on as an EXCEL Scholar, which is a paid position.) The school also has offered housing for anybody from the region who needs it.

Ceballos says the best thing faculty can do is to treat students first like human beings and then as students. “They can’t do their work if they’re traumatized and worried,” she says. Carr shares that concern for students: “How does REES, which is a very small program, take care of people with tremendous needs?” Sometimes, that just means spending time with a person. Like last semester, when Carr connected with Mokrii and, together, they held a Q&A event at Ramer History House to discuss Russian Jewish practices in Soviet and post-Soviet worlds.

For Janine Block ’94, assistant director of intercultural development and international student advising, it’s always been her calling to help students. She’s spent nearly 20 years at Lafayette providing transitional support for those living and studying in the United States: things like obtaining work visas, understanding immigration paperwork, or (more recently) navigating the travel restrictions due to COVID-19. But there’s another important aspect to her job—and it’s to create a home away from home for these students. “A lot of what I do is helping to build that sense of family and belonging,” says Block. As the adviser for the International Students Association, she works with the ISA board to coordinate year-round programming for students who might have atypical schedules—and needs. That could mean anything from planning excursions over semester breaks (when most American students leave campus) to setting up some home-cooked meals during Thanksgiving and Lafayette Family Weekend.

Her work intensified last semester after the invasion. Some examples? Students having trouble accessing their money due to Russia’s banking system shutting down. Others who were dealing with the guilt of being in a safe and comfortable environment on campus while loved ones back home were in danger. Some Pards have considered applying for asylum. “That’s a lot for anybody to carry,” says Block, “but especially for young students.”

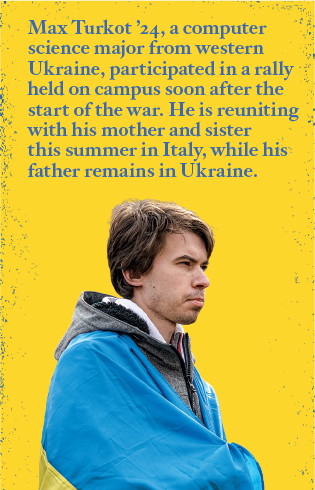

As a result, Block and her colleagues were in regular contact with students throughout the semester—and continue to be. One of them is Max Turkot ’24, a computer science major from western Ukraine. His hometown, Lviv, is approximately 40 miles from the Polish border. Turkot’s mother and sister left the country during the war to stay with relatives in Italy, but his father is still back in Ukraine. After talking to his family nearly every day throughout the semester, he’s finally reuniting with his mom and sister in Italy this summer.

Turkot says Block is one of the most helpful and compassionate people at Lafayette. Yes, she’s an invaluable resource for so many things from figuring out college housing to filing legal paperwork, but he equally appreciates the occasions when she’s just checking in on him. Others have been considerate, too, like his professor who’s allowing him to continue his research remotely in Italy so he can be with family. “I felt like people remembered what was happening,” says Turkot. “It’s really important that people didn’t forget.”

Turkot says Block is one of the most helpful and compassionate people at Lafayette. Yes, she’s an invaluable resource for so many things from figuring out college housing to filing legal paperwork, but he equally appreciates the occasions when she’s just checking in on him. Others have been considerate, too, like his professor who’s allowing him to continue his research remotely in Italy so he can be with family. “I felt like people remembered what was happening,” says Turkot. “It’s really important that people didn’t forget.”

Turkot, 20, also felt lifted up by the rally—starting with when he received President Nicole Farmer Hurd’s campus-wide email about it. “It was the first major thing the College did to respond to the situation,” he says. At the rally, Turkot was surprised to see how many people from the Lafayette community were closely related to Ukraine and who felt attacked by this war. He took a turn on the megaphone and shared not just his story, but also his gratefulness for all of the support on campus. He also asked people to keep finding ways to donate and help.

“The more people help, the sooner it will be over,” says Turkot. “I think that’s what everyone wants right now.”

Behind the Scenes

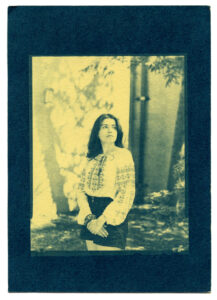

Photographer Adam Atkinson shares his portrait process

Photography is a powerful tool to evoke emotion and convey a story. As the editorial team discussed this feature, there was an understanding that the portraits of Deanna Hanchuk ’22, Prof. Joshua Sanborn, and Janine Block ’94 would need to strike the right tone. Adam Atkinson, director of photography and videography, felt inspired by the Lafayette community, who showed care and concern for international students from Ukraine and Russia. “The feeling, for me, was familiar to the photographs captured by Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Arthur Rothstein for the Farm Security Administration between 1935 and 1943. The images showed people who were experiencing difficult situations coming together around a makeshift table, huddled together in a car for warmth, conversing on a stoop after a hard day.” To capture that feeling, Atkinson pitched the idea of creating cyanotypes, an 180-year old printing process that produces prints in a distinctive blue hue. It’s a precise process. Atkinson shot each portrait using a Cambo 4×5 view camera and Ilford HP5 4×5 sheet film (which needed to be loaded into the camera in total darkness). Each image was created using yellow-toned paper that was pre-coated with potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate. When this compound is exposed to the sun, it hardens and bonds to the paper. Anything that has not been affected by the sun washes away in the rinse. A final spray of hydrogen peroxide immediately oxidizes the print and turns it a deep blueish hue. It was a lengthy process: “Modern photo paper exposes very quickly, sometimes in seconds,” he says. “Cyanotypes expose very slowly. These images took an average of 20 minutes apiece to expose.” Atkinson’s efforts give this feature a visual weight that conveys the importance of Hanchuk, Sanborn, and Block’s work. His use of yellow paper and blue hues pays homage to Ukraine, whose national flag features blue (representing peace) and yellow (symbolizing prosperity).