Dream Protector

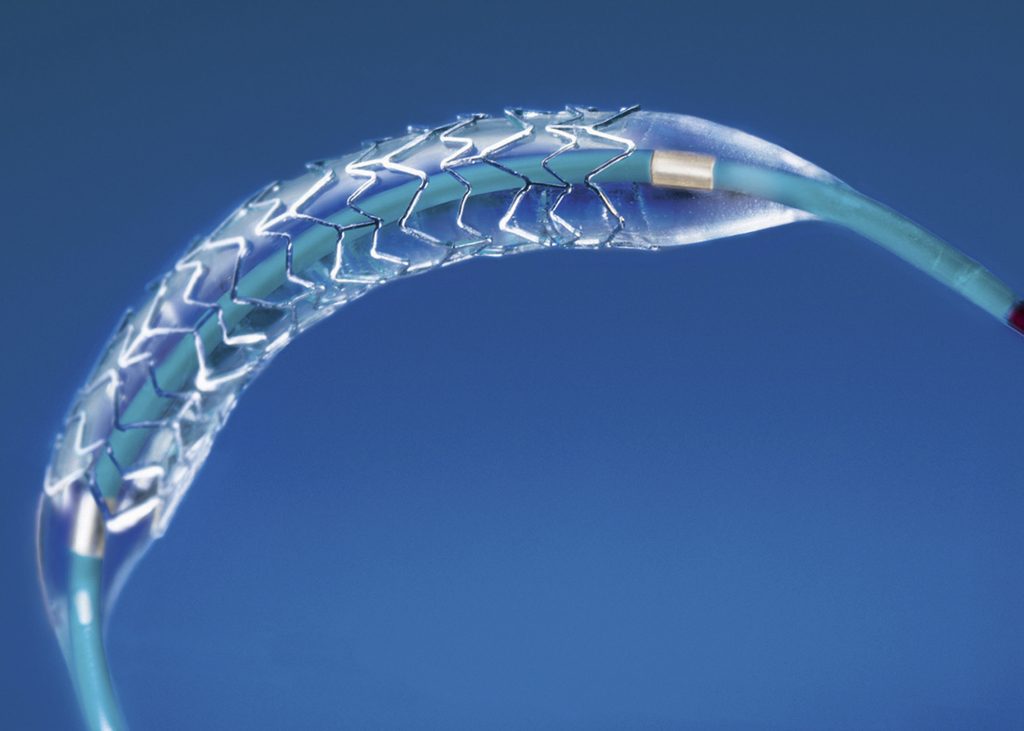

Before the 1990s, a clogged coronary artery usually meant one thing: heart bypass surgery, a costly and invasive procedure with a long recovery time.That changed with the introduction of a coronary stent, a slim metal tube inserted into the artery by inflating the vessel with a tiny balloon to keep the blood flowing.

“It changed the medical device world, and particularly the world of interventional cardiology,” says Scott Bluni ’89, who was working at the time for Boston Scientific, one of the largest medical device companies in the world. He helped the company in its efforts to develop a new kind of stent that would slowly emit a drug to keep the artery open.

The device—which required a special polymer coating—turned out to be a hugely successful product for Boston Scientific and a lifesaver for millions of patients.

But Bluni isn’t a doctor or an engineer—he is a patent lawyer, an often overlooked but just as essential part of the invention process.

“There are patents for the types of polymers, patents on how to get the drug into the polymer, and patents on the actual drug,” he says. “Patents on the method of treating patients with the drug, patents on the balloon to deliver it to the artery, patents on the catheter to deliver the balloon…” Bluni ticks down a partial list of the hundreds of patents involved in developing the device.

Patents allow innovators to be creative and bold.

And without any one of those, Boston Scientific’s drug-eluting stent may not have existed at all.

“Patents allow innovators to be creative and bold,” says Bluni. “They are what you need if you want to change the world.”

That’s because an innovative idea isn’t enough. For entrepreneurs to make a meaningful impact, they need to form a business to implement their brilliant new product and service. To create a business, they need to raise money from investors, and investors are not going to front cash unless they know that their investment is protected.

“If there isn’t some economic value to the entrepreneur in using an innovation, they are going to seek another route,” says Bluni, who spoke on campus this spring at the Essentialsof Entrepreneurship Conference sponsored by the Gladstone T. Whitman ’49 Endowment Fund and the policy studies program.

Bluni now works as an owner and partner at Kacvinsky Daisak Bluni (KDB), a boutique patent law firm that works on the cutting edge of innovations in medical devices and high-tech. The firm itself is also innovating the industry. Even though he has a small office on the North Shore of Boston, Bluni spends much of his time in a co-working space in the heart of the downtown, a block from the Public Garden and Copley Square. Young entrepreneurs lounge on leather swivel chairs and jewel-tone velvet couches while they help themselves to coffee and tea at a small bar area that also has beer taps for the end of the day.

“I’m like always the oldest person here,” Bluni jokes, leading the way to a conference room filled with Target-esque tchotchkes. By renting the co-working space the firm is able to keep its overhead low and get an edge over big, cumbersome law firms in keeping with the desire of today’s startups for a higher-value, but also more personal, patent attorney.

Potash and Pearl Ash

Patents were created hand-in-hand with the creation of the United States. The federal government started the patent system in 1790, a year after the Constitution was ratified. The very first patent, approved on July 31 of that year, was given to a Philadelphia inventor for potash and pearl ash, forerunners to baking soda, “by a new apparatus and Process.” It was followed that year by patents for a new invention aiding the manufacture of candles and an automated flour mill.

The office quickly grew, doling out more than 10,000 patents annually by 1836. Now the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office certifies some 300,000 patents annually, with companies like IBM, Google, and Apple each filing thousands each year.

In order to file a patent, says Bluni, “you have to show that an invention is novel, and that it is not obvious.” In other words, it can’t just be something that puts together two previous inventions in a predictable way. After securing a patent, the inventor has a monopoly on producing the invention for a set period of time—usually 20 years.

“In return, what society gets is a description of the device,” says Bluni. “That becomes part of the pool of technology other people can learn about and maybe say, ‘I can improve on that.’ That in turn snowballs into a better technology framework overall.”

The public nature of a patent makes it different from a trade secret, which remains proprietary for a company. “The classic example is the Coca-Cola formula,” says Bluni, “but there are many other examples of trade secrets that lasted far longer than 20 years.” One of his favorites is Lena Blackburne Baseball Rubbing Mud, a chocolate-brown muck sourced from a secret New Jersey location that is reputedly used by every Major League Baseball team to de-slick its balls. While a trade secret can last much longer than a patent, “once it’s made public, it can no longer be protected,” says Bluni.

Engineering a Law Degree

Bluni originally intended to be an engineer, noting that “I didn’t go to Lafayette because I dreamed of becoming a lawyer.” He grew up in the small Long Island town of Coram, where both of his parents were schoolteachers. He excelled in math but also enjoyed English classes. Lafayette seemed the perfect fit as one of the few liberal arts colleges with an engineering program. He majored in metallurgical engineering, figuring it would be a marketable skill in the Lehigh Valley, once home to Bethlehem Steel, the second largest steel-making manufacturer in the nation.

Heading across the valley to enter a Ph.D. program in materials science at Lehigh, his interest in business deepened. While there, he took a private course in patent law.

“I thought it might be an interesting way to see a lot of interesting technologies across a broad range of areas,” he says. The more he learned about patents and their role in innovation, however, the more fascinated he became.

Scott Bluni ’89 was instrumental in helping develop Boston Scientific’s first-generation drug-eluting stent, called the TAXUS Express Coronary Stent System, and securing the hundreds of patents required to bring the device to market. Boston Scientific Corporation (AP Photo/Boston Scientific, File)

After earning his doctorate, he headed to Washington, D.C., to work as a patent examiner at the Patent and Trademark Office during the day; at night he attended law school at George Washington University. Afterward, when an opportunity arose to join intellectual property firm Kenyon & Kenyon, he took it. A few years later, wanting to get back to the Northeast, he threw his hat in the ring for a position at Boston Scientific, located in the Boston suburbs. He worked there for eight years as an in-house patent lawyer specializing in medical devices, with his primary responsibility being the protection and enforcement of the company’s intellectual property assets relating to drug-eluting stents. Over time, his responsibilities grew to include business divisions for cardiac surgery, urology, neurovascular, oncology, and other areas.

While working at Boston Scientific, he contributed enough to the innovations made by the R&D team to be named as a co-inventor on three patents with names like “block copolymer particles” and “ureteral stents and related methods.”

New Challenges

Eventually, looking to get back into private practice, Bluni left the company to head up the intellectual property division of Bingham McCutchen, a huge Boston-based law firm with more than 800 employees. After difficulties brought on from a string of mergers and overreliance on a few key clients, however, the firm was acquired by competing firm Morgan Lewis in 2014. By the time it did, Bluni had already jumped ship to become a co-founding partner in KBD, establishing a New England presence for a small law firm started years earlier by former colleagues from Kenyon & Kenyon.

The company has only 35 attorneys, yet it counts among its clients Boston Scientific, Intel, Facebook, Microsoft, CVS Caremark, and a number of other household names in addition to smaller technology firms located throughout the country.

Recent developments in patent law have added new challenges to his job. For years, the United States was a “first to invent” country, meaning that it didn’t matter when inventors filed for patents, so long as they were diligent about recording when they came up with an idea in order to prove they did it first. Under the Obama administration in 2013, however, the U.S. changed to a “first to file” country to bring it in line with almost every other country in the world.

That has created a dilemma for companies about exactly when to file—too soon and their secret may be spoiled before they are ready to take advantage of it; too late and they risk someone else patenting it first. One possible solution to that dilemma, Bluni says, is to use a strategy that allows inventors to file a provisional patent as a placeholder with just the bare bones of an idea, so long as they follow up with the full idea within a year.

Another legal development has wide-ranging implications for high-tech and medical inventions. In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously struck down a patent by Alice Corp. for a form of banking software, saying it was proposing an “abstract idea” rather than a technical invention. As such, it was ineligible for protection.

“Software can just be an algorithm or a series of steps you are instructing the computer to do,” says Bluni. “It can be viewed as just a mental process that you could do in your head.”

The ruling had a chilling effect on the software industry, with courts invalidating hundreds of software patents based on the same logic. It had a similar effect on a broad array of industries, including the medical industry, where oftentimes patents are claimed for methods of diagnosing patients or administering drugs.

The courts did on appeal reverse a few decisions last year, giving life support to software patents. “The pendulum has swung way to the side of tearing down these patents,” says Bluni. “I think the pendulum is going to start swinging back.”

As new technologies emerge in burgeoning fields such as biotechnology, patent law will continue to be put to the test. As these cases and those like them play out, one thing is clear—those inventors and dreamers seeking to change the world will always need a good patent lawyer by their side.