Connecting: Giving Guidance, Learning Patience (Saul Cooperman ’56)

by Saul Cooperman ’56

I worked in suburban school districts for 22 years as a teacher, principal, and superintendent of schools. As New Jersey’s commissioner of education, I visited our major cities and met with leaders in those cities. I also increased my understanding of urban America when I created, with Tom Glennan of the Rand Corporation, the New American Schools. Based in Washington, D.C., the organization funded schools in urban centers throughout the nation.

In 1990, I began working with families in Newark, N.J. I saw the problems of the children due to absentee fathers, poverty, and frequent moving. In 1995, I started the 10,000 Mentors program. Within a few years, it became the largest in New Jersey. Big Brothers/Big Sisters saw its uniqueness and absorbed it into their national program, which was great for us.

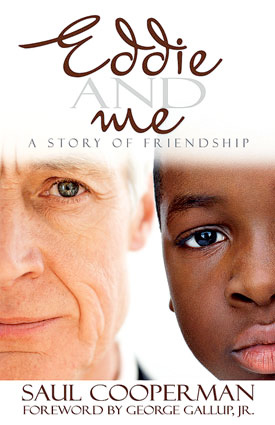

I became a mentor to a young man, and my book, Eddie and Me: A Story of Friendship, is about our almost 15 years together. Since I was the father of three children, had been a teacher and principal, and thought I knew something about the urban territory, I thought I would be a good mentor. My logic was faulty. Working on policy issues, creating programs, and building organizations was different from working with one young boy. Very different.

FRIENDSHIP AND STRUGGLE

Eddie and I met in the summer of 1995. Eddie lives in Newark, N.J., about one mile from where I was born. On one hand our relationship is about friendship. It’s also about my struggle to help raise Eddie to be a caring,

self-sufficient person, ready to meet the challenges he must face as he grows toward adulthood. Challenges of poverty, drugs, violence, and low expectations. The challenge of a collective mindset that says, “I can’t”

rather than “I can.”

Our friendship may seem a little strange because it does not look like we have a lot in common. As I said, I met Eddie when he was 8, and I was 60. So our age difference might seem to be an obvious handicap. By American standards, Eddie is poor. I’m not. I’m white. Eddie is black. When I was first matched with him, he was with his mom, Celie. I remember I asked why she wanted a mentor for her son, and she said she wanted

someone to help “raise her boy the right way.” I asked if it wouldn’t be better to match Eddie with an African

American man, because they would have more in common. She said, “It doesn’t make any difference to me if it doesn’t to you. I just want him to learn the right thing to do.”

So, this is a story about friendship and struggle, about the things that have happened to us over the course of 14 years. Many more knowledgeable people than I have written about the larger social issues facing children in a tough urban setting, so I won’t write about those. I will, however, talk about Eddie’s environment, which often conditions his approach to life, and his thoughts about the future.

YOU THINK I’LL HAVE A CHANCE?

Anyone who has seen Newark’s worst sections knows how hard it is for children to be brought up safely, surrounded as they are by things most Americans want to keep away from their children. Any day I go into Eddie’s neighborhood, I am concerned about drug distribution, car-jacking, or random violence.

These are terrible enough, but the day-to-day realities of life in Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, or Newark take a different type of toll on the human spirit. I’m thinking of the subtle pain that goes along with the noisy, overcrowded homes, where privacy is sometimes unknown, or the unwashed windows of homes that outnumber the soot-stained leaves on the only tree on the block.

As Eddie and I began our friendship, I found myself thinking back to some really basic parts of my own life. I had to sidestep temptations, and I’m sure I tripped over opportunities I didn’t see. I stumbled often, but my mother and father, as well as relatives and neighbors, were always there to help me up and point me in the right direction. I had support and many “invisible hands” that I didn’t know were working to see me raised right. My first eight years were very different from Eddie’s.

As we were getting to know each other, Eddie would talk to me about his neighborhood. I remember him once saying, “See that kid on the bike? He delivers packages to drug dealers. He tells me they give him a couple of dollars every time he takes a message or package from one guy to another.”

One day, when we were returning to Eddie’s home, we drove by the Althea Gibson preschool. I told Eddie who Althea Gibson was and that she excelled in a sport that didn’t have many black players. He seemed interested in Gibson and her achievements. The next week I gave him a book entitled African Americans Who Were First. It talked about famous African Americans and some lesser known individuals such as Wesley Brown, who was the first African American graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy.

During the next few weeks we read about many of the people in the book, and I thought the message of studying, working hard, and persistence might be getting through. We talked about how hard it was for those people to accomplish what they did. We talked about prejudice, fairness, and justice.

“Do other people have to go through all this stuff, or only black people?” he asked.

“Lots of people have problems, Eddie.” I explained what “Jewish” meant, and told Eddie that I was Jewish. Sometimes people hurt me a lot, and I told him about the fraternity system at Lafayette College when I went there. “Only four fraternities would accept Jewish students, although there were 21 fraternities. My friends had a chance to get into all 21. I didn’t.” I told him that, 20 years later, as a member of a Lafayette College Trustee Committee, I stayed at a Pocono Mountain resort. I liked the laid-back atmosphere of the resort and suggested to my wife, Paulette, that this would be a great place to spend a weekend.

A few months later, we decided to make a reservation. When I called, I was told that all rooms were taken. I felt uncomfortable with the tone of the employee and told Paulette that I felt the employee’s voice changed when I said my name was “Saul Cooperman.” She said I was probably hearing things that weren’t there, but said she’d call and give a fictitious “non-Jewish” name. When Paulette called five minutes later as Mrs. Allen Johnson, they asked her, “What type of room would you like?”

I explained to Eddie that the name Saul Cooperman got a rejection, while Mrs. Allen Johnson had her pick of rooms. Eddie understood. He understood that prejudice was often worse toward blacks, but they didn’t have a monopoly on it. We talked about Asians and Italians as people who have suffered. I explained that all people have an opportunity in America, even if there is prejudice.

“You really believe that, Mr. Cooperman? You think I’ll have a chance?”

“Yes I do, Eddie. In America, you’ve got to work to get somewhere, but in this country you can have the opportunity. You will have to deal with some people who won’t be fair because you are black. But, there will also be good people who will judge you on what type of person you are and how well you work. And there are many of these people in our country.”

“I hope you’re right,” he said.

Eddie was not completely persuaded that he would be given a fair chance. Many voices and experiences have taught him a contrary view. But, at least I knew he was beginning to trust me. That was important, and I hoped it would be enough for him to really listen to me. As I drove home, I was sad that a 9-year-old kid could not believe he had a chance.

DANGEROUS PATTERNS

Eddie is in the fifth grade, and he makes mostly Ds on his report cards, with an occasional C thrown in. He has made one B in his core subjects and also an F. He’s the sort of kid who just wants to get by. And a C in Eddie’s school might be a failing grade in a good suburban school.

“Eddie, you say you know it’s important to read well, but you don’t make any effort to do better. Do you think something magical will happen, and suddenly you’ll be a good reader?”

“I know I have to do better, but it’s hard for me.”

“I won’t accept that. You work hard on your head fakes and crossover dribble, and I see improvement. You improve because you work at it. You don’t work on your vocabulary, so how can you improve your reading?”

“I want to do better. Sometimes I forget to bring my books home.”

“That’s a bunch of crap, Eddie. You know it, and I know it.”

How in the world do I get him to see the value of reading well? I knew a dangerous pattern of failure was developing. Just as success breeds success and encourages kids who do well to continue to do well, there is a similar current that sweeps through the lives of children who fail. Discouraged, fatigued, impoverished, they soon establish self-defeating routines that keep them from catching up with their peers in suburban schools.

These patterns were there. Most of his friends didn’t care about school, so why should he? Eddie told me that older kids put down anyone who does well, saying they are “acting white.” He doesn’t see anyone who reads for pleasure. I’ve never been so frustrated. . . .

I almost gave up, but I learned that persistence, dogged persistence, would be the key ingredient if I were to succeed with Eddie. I had to see him often, let him know that I would be there for him, because at a young age he learned that most adults were not dependable. And I had to keep at the values that would mold his character, because this was the be-all and end-all for me. We had some difficult times, especially when Eddie dropped out of high school.

“I AM SO HAPPY”

It’s 2005, Eddie is 18. He kept his word about studying for the GED, using the workbook I had given him.

After two tries, he passed four of the five sections on the test. He had failed math, his nemesis. [A few weeks later he took that section again.] “I got it, Mr. Cooperman, I passed the math, and I have the certificate in my hand. I am so happy.”

Finally! When he got off the deck, I could see the determination in his voice and see it in his eyes. He was ready to grow up.

Eddie (real name: Johnny Harris) is now 22 years old. We meet at a diner in West Orange every few weeks to keep up with each other’s lives. He is just a few months away from earning an associate’s degree in computer information systems from DeVry University. And I am talking with my contacts to help him find a job.

When I began this relationship I thought I knew the territory. I knew children, having raised my own, but this was different. I learned to understand and respect his environment. And, after the first year or two, something else was growing inside of me. Slowly but surely, friendship became caring for him, and then caring slowly moved into the emotion of love. Yes, I love Eddie very much. I know that I will be with him for the rest of my life. He is an integral part of my life. And that makes me feel very, very good.

Portions of this essay are excerpted from Eddie and Me: A Story of Friendship (Intermedia Publishing Group, 2010), available from Amazon.com.

Saul Cooperman, of Bernardsville, N.J., is a lifelong educator. He has been a teacher, a high school principal, and superintendent of schools in Montgomery Township and Madison, N.J. He was commissioner of education for New Jersey from 1982 to 1990. In the 1990s, he became president of the R.E.A.D.Y. Foundation in Newark, set up to assist families with the support they needed to raise their children. The recipient in 1986 of Lafayette’s George Washington Kidd Class of 1836 Award for public service, he is the author of How Schools Really Work: Practical Advice for Parents from an Insider (Open Court, 1999) and has published nearly 70 articles in professional journals. He holds a master’s degree and doctorate in education from Rutgers University.

Saul Cooperman, of Bernardsville, N.J., is a lifelong educator. He has been a teacher, a high school principal, and superintendent of schools in Montgomery Township and Madison, N.J. He was commissioner of education for New Jersey from 1982 to 1990. In the 1990s, he became president of the R.E.A.D.Y. Foundation in Newark, set up to assist families with the support they needed to raise their children. The recipient in 1986 of Lafayette’s George Washington Kidd Class of 1836 Award for public service, he is the author of How Schools Really Work: Practical Advice for Parents from an Insider (Open Court, 1999) and has published nearly 70 articles in professional journals. He holds a master’s degree and doctorate in education from Rutgers University.