Dec 16, 2014

Going Further

In an intellectual collaboration that stretches the frame of interdisciplinarity, a diverse group of students, faculty, staff, and alumni is exploring…

In the Brain-Computer Interface Lab. Camila Moscoso ’16 (L-R) and Maura Schlussel ’15 adjust electrodes on cap worn by Brandon Smith ’17 that records brainwaves. Looking on are Alexandria Battison ’16 (foreground) and Prof. Lisa Gabel (L-R), Alexandra McCullough ’16, Tom Fuller ’16, and Prof. Yih-Choung Yu.

By Kate Helm | Photography by Chuck Zovko

Clean water and food for an increasing world population, transnational organized crime, outbreaks of diseases with no cure, sustainable development in the face of global climate change, the widening gap between rich and poor, ongoing ethnic conflicts and terrorism, and managing limited natural resources—just a few of the challenges that characterize the global crisis.

Students will step into this world of complex, multifaceted situations when they graduate. While developing a depth of knowledge in one field is still fundamental, at Lafayette they also are engaged in courses and experiences beyond their chosen majors. Having the ability to think about a problem from a different point of view and synthesize knowledge from multiple perspectives prepares them for leadership and success.

“A learning environment that includes both liberal arts and engineering more accurately represents the real world,” says Michael McGuire, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering. “For example, our nation’s infrastructure crisis is as much a social and political problem as an engineering problem. Students who learn how to approach problems without blinders on will be well prepared to develop balanced solutions to complex challenges. Coming from a large research university, I am regularly amazed by how few barriers exist between academic departments here.”

Unexpected discoveries reside in that collaborative space. Indeed, recent research has dismissed the misconception that analytical thinking is confined to the left side of the brain and creativity to the right. The study showed that it is the connection among all brain regions that enables humans to engage in both creativity and analytical thinking.

Engineering students benefit from exposure to the liberal arts, which helps them imagine and understand the social, cultural, and political consequences of implementing new technologies. And vice versa, students majoring in liberal arts fields benefit from engineering because it helps them develop a deeper, more well-rounded understanding of modern technology and how this powerful knowledge can be applied in a responsible, inspired manner.

Take Alexandra McCullough ’16, for example. A neuroscience major, she is a member of the brain-computer interface lab advised by Lisa Gabel, associate professor of psychology, and Yih-Choung Yu, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering.

In the lab, users wear a cap placed over the sensorimotor cortex that has electrodes to record EEG signals. The electrodes pick up a brainwave called the mu rhythm that registers when someone moves as well as when they only imagine motor movement. This research could potentially enable patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, to regain mobility by controlling assistive devices using thoughts.

Over the summer, McCullough was part of an interdisciplinary team that included electrical and computer engineering majors Tom Fuller ’16 and Brandon Smith ’17 and neuroscience majors Maura Schlussel ’15 and Alexandria Battison ’16. The engineers designed software for the BCI device, and the scientists conducted experiments with human subjects. They found that collaboration was crucial to their success. McCullough and Fuller also worked together to optimize a wireless device for improved functionality. This device would work in a similar way by detecting neural activity and allowing the user to interface with computer software, but would also allow for more mobility, thus more freedom and improved quality of life. Working with engineers helped McCullough learn the importance of breaking a project down into smaller units. “They showed me that we had to perfect one part first and then build on that for the next step,” she says. In addition, she says Tom used his expertise to transform 12 steps they were using on the computer down to two. “It streamlined the process and minimized mistakes.”

She notes, however, that because the brain cannot be reduced to a simplistic program, they worked together “to find the best equilibrium of both neuroscience and engineering.”

Brian Skalla ’16 (L-R), Hailey Votta ’15, Prof. Laurie Caslake, Prof. Michael McGuire, and Erika Hernandez ’17 work together in Acopian Engineering Center using the dust-measuring apparatus designed by Skalla and Hernandez.

That kind of collaboration is the premise of the Center for Innovation, Design, Entrepreneurship, and Leadership, which brings together engineering and liberal arts students to work on innovative solutions to real-world issues. Last year the mechanical engineering department’s Formula SAE race car senior design project was offered to all majors for the first time through IDEAL.

Designing a race car is, on the surface, strictly an engineer’s job, but the project is really one of entrepreneurship, not design, explains Scott Hummel, Jeffers Director of Engineering. The idea is to create a business plan and a prototype race car for a start-up company that is going to sell 1,000 cars a year to weekend enthusiasts. Engineers often focus only on performance, but a manufacturer also must consider profits, societal impact, marketability, and user satisfaction.

“Students from the liberal arts and engineering need each other to do well,” says Hummel. “Modern product development teams are made up of cross-functional members who have backgrounds in engineering, business, finance, art, policy, government, and more. Engineering is simply not the end-all in design.”

Brian Skalla ’16 agrees. He says that without the contribution of differing expertise from the members of the group that he is working with, there would be little progress. His team includes biology major Erika Hernandez ’17 and fellow civil engineering major Hailey Votta ’15. They are evaluating a biodegradable treatment for unpaved roads through the EXCEL Scholars undergraduate research program with McGuire and Laurie Caslake, associate professor of biology.

” I draw on my experience from the Syrian Town project when working on conservation plans. Creating a complete picture requires a knowledge of geology and biology of the site but also an understanding of the historic and cultural context.”

—Kelsey Boyd ’11

Natural Lands Trust

On dry, untreated gravel roads, mechanical disturbances and air currents from passing vehicles create dust clouds that include a fraction of dust called PM10, an EPA-identified air pollutant that can cause heart disease and asthma. Current solutions include water, which evaporates quickly, or salt-, petroleum-, or plant oil-based solutions, all of which can be harmful to the environment. The group is exploring an algae-based dust palliative to form biofilms, which will keep fine particles from becoming airborne and have less negative impact than the salt- and oil-based treatments.

Hernandez is searching for non-pathogenic bacteria that can survive hot and dry conditions. For example, she monitors bacteria growth by applying it to aggregate in a closed container. Initially, she was going to apply the bacteria by counting the number of cells, but Votta and Skalla were concerned that the water volume remain constant for all treatments so that it would not be a variable in the results. Since different bacteria have varying amounts of water, she adjusted the amount of bacteria.

Engineers know that an innovative design means little if they cannot communicate its features and benefits to a non-engineer. By “teaching” Hernandez and Caslake about the testing apparatus she and Skalla designed and built, for instance, Votta gained a fuller understanding of why they had made certain decisions in the process.

During testing, warm air is blown through a wire-mesh test chamber containing a sample of road gravel prepared with dust palliative, which becomes less effective as the sample dries out. Sensors measure temperature, relative humidity, and air flow velocity, enabling the team to observe the relationship between dust production and the relative dryness of the gravel in real time.

The team is working with faculty from Oregon State University’s College of Forestry on a proposal for National Science Foundation funding to study stabilization of unpaved roads using biologically derived materials. The testing apparatus will be an important part of the proposal.

Not only are students learning to think in a range of disciplinary perspectives, but the collaborations also produce results.

The race car team took home three first-place honors at the Formula SAE Collegiate Design Series in May at Michigan International Speedway. They competed against 120 teams from colleges and universities in the U.S. and abroad.

“The depth and breadth of this project required a team with diverse interests and skill sets,” says Mitch McNutt ’15. “Our strategy resulted in the team presenting an overall stronger product than engineers working alone could have done.” They were right.

McNutt, who is pursuing a dual degree in mathematics and economics, says that his lack of technical knowledge was apparent on the team comprised of mostly mechanical engineering majors, but learning why and how the design team made its choices helped him do his job better. He created and presented a business model and cost report documenting every part of the car down to the nuts and bolts.

“Working with McNutt helped us streamline the manufacturing process and realize the real-world monetary importance behind effective engineering design,” says Matt Tindall ’14, who graduated with a B.S. in mechanical engineering and is now with Motivo Engineering in Torrance, Calif.

Learning to embrace different perspectives on College Hill translated to success on the job for Kelsey Boyd ’11, Green Hills Conservation Stewardship Plan intern for Natural Lands Trust in Media, Pa. She and Anna Eisenstein ’13 worked as EXCEL Scholars on Andrea Smith’s “Syrian Town” project, which began in 2007 in response to interest among elderly community members and as an opportunity for students to conduct field research.

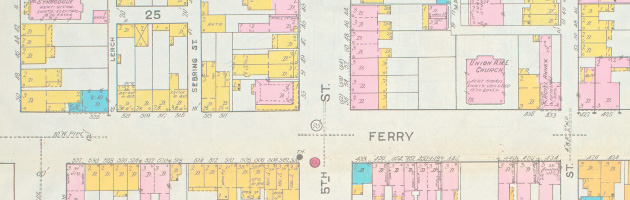

Syrian Town, a multiethnic neighborhood at the heart of Easton, was dismantled in the 1960s during an urban renewal project. Once composed of Lebanese-, Italian-, Anglo- and African-American residents in roughly equal proportions, it lives on in the memories of former residents. Smith and her students have been reconstructing the neighborhood using old First Insurance Company maps and other images, a database of former residents, and oral histories. A multimedia website will present the “virtual neighborhood.”

A First Insurance Company map from 1919 has been used to help reconstruct a virtual representation of the old Syrian Town neighborhood in Easton.

Smith, associate professor of anthropology and sociology, has involved students from her field but also from geology, policy studies, and government and law.

Boyd, a geology and policy studies graduate, used geographic information systems to reconstruct the layout of the neighborhood. Using GIS for a project not related to environmental science pushed her out of her comfort zone. Today, she uses GIS to assess natural resources in conservation areas, information that is used to determine management plans for protected areas.

“I am constantly drawing from my experience with the Syrian Town project when working on plans,” says Boyd. “Creating a complete picture of a conservation parcel’s resources requires not only a knowledge of the geology, biology, and hydrology of the site, but also an understanding of the historic use and cultural context of the area.”

Eisenstein says, “By embracing perspectives from multiple disciplines, which at first seemed separate, we came to see deep and unexpected connections in their significance for the people who had lived there.” Now a doctoral student in anthropology at University of Virginia, she adds, “That experience continues to influence how I perceive and how I respond. I am much slower to decide how I feel, more willing to entertain other points of view, and often don’t feel I have a full understanding of a given situation. Being willing to consider things without necessarily settling on an answer is a more responsible way to engage social life.”

Smith and her first research assistant, Rachel Scarpato ’08, coauthored an article about the language of blight and the loss of a neighborhood to urban renewal for The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. The recipient of a degree in anthropology & sociology and American studies, Scarpato went on to earn a master’s in education from Harvard and is a fourth-grade math teacher and instructional coach at Lawrence D. Crocker College Prep Charter School in New Orleans.

Prof. Andrea Smith and Walter Burkat ’16 scout blocks in Easton to determine buildings that still remain from when the area was known as Syrian Town.

She says she learned about the importance of precision in data collection and writing from her sorority sisters who were engineering majors. “Although I did not take engineering courses, I benefited from interacting with students who did. I observed their methods, which I now apply as I ‘engineer’ assessments and lessons. I strive for each question to give evidence of the understanding or misunderstanding a student has about the topic. In lesson plans, I consider every last detail to avoid confusion or wasted learning time.”

Smith’s current research assistant, Walter Burkat ’16, helped write a section for a book on Lebanon’s relationship to France and how it influences people’s memory of the home country. He also has conducted interviews.

“This project has shown me that a story has multiple sides. In one neighborhood in Easton, we have found that not everyone can agree about why redevelopment occurred.”

They are working with Eric Luhrs, director of digital scholarship services, and John Clark, data visualization and GIS librarian, on the website.

Burkat lives in McKelvy House, a living-learning community of about 20 students that focuses on interdisciplinary intellectual discourse. Like Scarpato, he has benefited from his interactions with engineering majors there.

“I consider myself lucky to be at a college where multiple interests can be combined to make something special. Our society has set rigid structures for disciplines, and we are taught to specialize, specialize, specialize. Using an interdisciplinary approach helps us create several methods for solving a problem. It’s like a carpenter using multiple tools to create a masterpiece. Thinking about something from multiple perspectives helps us see the full picture. Lafayette has definitely embraced this ideal.”

When the house hosted a discussion on mental illness in America, for example, Burkat, a double major in anthropology & sociology and French, discussed the social stigma. Economics majors discussed the financial ramifications, and the biology and chemistry majors presented the science behind the condition.

“Disciplines are, in a way, artificial frameworks that help carve out a piece of the world in a certain way,” explains Smith. “Once students recognize that, and have the experience of thinking in and out of different disciplinary frameworks, they really are developing a relationship with their own intellect.”