Last Line of Defense

A few weeks before McCrae Williams ’21 died, he traveled to Fiji with his family to dive the Great White Wall, a swaying, 600-foot hedge of soft coral and frilly sea fans.

Beneath the water, the coral appears shadowy gray. But when the moon is full and tide just right, the wall blooms a brilliant white, transforming hilly reefs into what look like snow-capped peaks.

“We were at 105 feet when we saw it happen,” says McCrae’s father, Chris Williams.

McCrae, who died Sept. 12 from a head injury sustained during a fall in his dorm room, was a certified scuba diver with a passion for travel instilled from when his family lived in London for a few years. Having a mother who works as a safari planner also abetted his wanderlust.

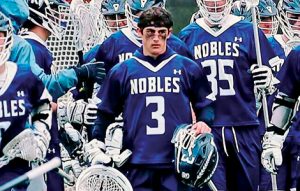

McCrae Williams ’21 was captain and goalie of his high school lacrosse team at Noble & Greenough School in Dedham, Mass.

“He’s been to almost every continent,” says Chris. “Wherever we traveled, we would visit orphanages and rural village schools. McCrae had a big part in organizing our family’s contribution of books, gifts, sports equipment, or educational materials to those less fortunate. This was very important to him.”

A goalie for the Lafayette lacrosse team with aspirations of becoming either an orthopedic surgeon or finance manager, McCrae also had a love for the arts. Over the summer, he parlayed his talent for photography and video editing into a job by shooting drone videos for real estate agencies, developers, and billboard companies.

He also enjoyed drawing. “He was a multidimensional kid,” says Chris. “He took a lot of pride in what he did. He loved school. He wanted to do well in whatever he did.”

Nancy Waters, associate professor of biology, who served as McCrae’s first-year adviser, discovered that when she asked him to answer a series of questions before their first meeting. Prompted to list the four things he most wanted to accomplish at Lafayette, McCrae replied: Succeed academically and athletically, make everlasting friendships, build on social skills, and graduate with a major and minor.

McCrae liked to think of himself as his team’s “last line of defense,” says his father, Chris. “Having the team’s back was really important to him.

“He was a real presence,” says Waters. “He smiled the whole time. He had a great smile. He was clearly happy to be here, and his family figured strongly in most of what we talked about as did his interest in exploring so many things here.”

Math Professor Rob Root, who had McCrae in his First-Year Seminar, says he didn’t know McCrae well, but glimpsed an expression of “intellectual grit” in the young man after Root commented that his writing log needed improvement.

“He came up at the end of class and handed in a new writing log,” says Root. “All the students were dropping off their logs, so there was much hustle and bustle as students came and went, with some students asking brief questions. McCrae didn’t say a word, but as he turned in his log, he gave me a look of resolve and determination, as if to say, ‘I get that you want more from me, and I know that I am up to it; see if this doesn’t prove that.’”

That describes McCrae, says Chris, noting that his son was incredibly mission oriented.

“He carried a list on his phone of children’s names for when he had kids. He had his goals written down on his phone.” He also liked to think of himself as the “last line of defense” and wrote “Psalm 3:6” on his lacrosse helmet in homage to the words “there is no fear,” says Chris. “He lived by that. Having the team’s back was really important to him.”

He also was known by his coaches as a fierce competitor, “filled with courage, consumed with perseverance, and a true leader who lifted his teammates’ love of the game to the next level,” adds his mother, Dianne.

After McCrae died, a student told the family she hadn’t known their son very well, but he walked her home one night to make sure she was safe. “He really did like helping people, yet he never wanted attention for it,” says Chris. “After he passed, we learned from a teacher who was in a bad car accident that McCrae emailed him over the summer to send healing thoughts and to tell him to fight back with all his might.”

Deciding to donate McCrae’s organs was an easy call because he would have wanted to save someone else’s life if he could, says Dianne. “They’re all doing great,” she says of the five recipients.

After McCrae died, the family came together, and using words that started with each letter of his first name—mission, courage, character, respect, academics and empathy—tried to define a young man they all dearly loved.

“McCrae had strong family values,” says Dianne. “Many times he would opt to come home for dinner rather than eat out with friends. Time at the dinner table was important. We were his ultimate team.”