Faster Forward

One day in early spring 2017, Matt Kramer ’14 strolled into the lobby of Gillette Stadium in Foxborough, Mass., and told security he had a meeting scheduled with the strength-and-conditioning coach of the New England Patriots.

No such meeting existed. But the ruse got the Lafayette mechanical engineering graduate past the front gate, upstairs to a reception desk in the Super Bowl champions’ front office.

“Is he expecting you?” the receptionist asked.

“Oh, yes,” Kramer said. He told the woman he’d been sent by a strength-and-conditioning coach from another team. That was partially true; though no meeting had been made, through his business, Kramer knew a guy who happened to know the man he wanted to see. Or rather had to see, because this was the Bill Belichick Patriots, the It team of pro sports, the oft-emulated winner of five world titles since 2002.

Kramer’s connection was thin. For an engineer turned startup company executive, this was Kramer’s Hail Mary shot at landing as a client one of the most influential franchises in all of sports.

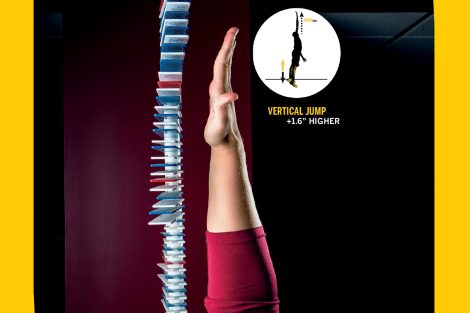

And it worked. Kramer gave his spiel for VKTRY, the insole he helped develop from aerospace-grade carbon fiber, which, while allowing athletes to jump higher and run faster, protects them from injury.

“The Saints are using it,” Kramer told the coach. “We’d love for you to try it.”

“OK, cool,” he said. “Come back in one week.”

A week later VKTRY CEO Steve Wasik returned to Gillette and closed the deal. And nearly a year after that, as Kramer sat in U.S. Bank Stadium in Minneapolis to watch Super Bowl LII, he knew some of the Patriots were sprinting, jumping, and strutting on wedges of carbon fiber he’d helped develop, fine-tune, and sell. So were players for the Super Bowl champion Philadelphia Eagles, for that matter.

Kramer holds no degrees in marketing, but over the past three years he’s learned to swim the shark-infested waters of the sports industry. While he’s used his Lafayette knowledge of engineering to help hone an innovative product that’s catching the attention of athletes everywhere, VKTRY is an early-stage company with only a handful of employees. That means Kramer doesn’t just go on sales meetings, investor meetings, and fundraising events as a novelty. It’s a necessity.

“It’s brought me out of my engineering introvertedness, for sure,” he says.

His college and his business have helped Kramer mimic the material with which he earns his living—carbon fiber, the strongest material on earth, the stuff they make stealth bombers from. At the same time, carbon fiber is supple enough to take countless shapes.

It can do almost anything.

Something With My Hands

When he was accepted at Lafayette, Kramer knew he wanted to play golf for a Division I college and study some kind of engineering.

“I’d always been taking things apart, putting things back together from like age 12,” he says. “And I knew if it wasn’t engineering, it was something with my hands.”

He worked on the mechanical engineering department’s Formula One car, which at the time explored carbon fiber as a possible material.

When he graduated, he landed a job at Sikorsky Aircraft, the Stratford, Conn., manufacturer of Black Hawk helicopters. He helped design blades, working on a variety of projects including one that would render a helicopter silent.

It was a good job, but as Kramer settled in he saw his future stretching before him in a disturbingly narrow line. Ten years. Standard salary increase after standard salary increase.

“Maybe after that you get to work on your dream part,” he says.

Then one day he visited Matt Arciuolo, a family friend who owns Arciuolo’s Shoes in Milford, Conn., which has been in business for nearly 100 years. A board-certified pedorthist specializing in pain management and performance enhancement using custom orthotics and footwear, Arciuolo had done some interesting work in the world of sports shoes.

Years earlier, the U.S. bobsled team had asked him to develop a shoe that would help push off faster during a race. Arciuolo built an insole that concentrated energy and returned it to the athlete, essentially giving the bobsled team more spring in its step. He secured a patent on all 16 claims.

Kramer tried out a pair, slipping them into his size 10s and racing around the Arciuolo backyard.

He couldn’t believe his feet. “It’s like you’re standing on the edge of a diving board,” he says. “You can really feel it.”

“You’re a carbon fiber engineer,” Arciuolo said to Kramer. “Help me develop this.”

Scott Hummel’s Crucial Reprimand

So on nights and weekends in his parents’ attic in Milford—sometimes late into the night—Kramer researched carbon fiber insoles. He began asking questions at Sikorsky that pertained to flexibility of carbon fiber.

He discovered ways to cut the steep production costs, researched suppliers, found a carbon fiber manufacturer in Georgia. More and more it began to look as though a startup company geared to manufacture and sell Arciuolo’s creation might be where his future lay.

One stumbling block was reducing the thickness of the layers of carbon fiber while maintaining the balance and stability each insole required. Kramer needed help, so he called an old friend. Scott Hummel, William Jeffers Director of Engineering, sympathized and offered Kramer lab space in Acopian Engineering Center and a senior to assist him.

In the Lafayette labs, Kramer and his student helper tested thicknesses of carbon fiber at various parts of a foot, studied how the insole would be compressed, and determined the current thickness distribution.

As thickness of the fiber increases, the insole’s stiffness shoots up threefold. At one moment, Kramer forgot this property. Hummel reprimanded him. “You should know this,” he said.

Kramer’s former professor’s reminder turned out to be huge—the young engineer was able to develop the thinner product he needed.

A Company Springs to Life

In November 2015, the fledgling company obtained its first big investment. Kramer quit his job at Sikorsky and joined the startup’s ranks full time as the company’s chief engineer and eventually vice president of business and product development.

He’d dreamed of working at a startup just like this, but now the reality of what he’d done dawned on him. It was exciting, but self-doubt inevitably crept in.

“I’m not going to get a paycheck next week,” he’d think. “This isn’t working; I’m an engineer, and I’m trying to sell things online and on Instagram.”

Marketing and branding had always seemed superfluous, but now he found himself doing both—designing a website and developing these little carbon fiber miracles into a product someone might want to buy.

Even before securing that first investment, the company had hired serious startup firepower in Wasik. Since the 1980s, Wasik has developed a mile-long track record of developing brands and pushing startups into the stratosphere. The metal water-bottle craze? Wasik kicked that off as president of SIGG USA in Stamford.

“He’s awesome because he’s a forward-thinking, seasoned CEO but has no problem hitting the road for sales,” Kramer says. “You should see the guy at a trade show. Literally not a single person gets to walk in a hundred-foot radius without a sales pitch. None of us had built a company before. We knew we needed an experienced leader, but had no idea how vital Steve would be.”

In 2016, VKTRY launched its website. Confident athletes all over the internet would latch on and sales would soon follow.

Then, nothing.

“We had a really romantic idea of what this was,” Kramer says, laughing. “And then it’s like, ‘Oh my god.’”

It became clear that acquiring the company’s first clientele would involve legwork. So Wasik, Kramer, founders Matt and Felicia Arciuolo, and their son Christian (now head of operations) hit the road. They sent out email blasts, tracked down names on social media, and made cold calls.

The journey took Kramer a million miles from the engineering lab of his comfort zone. At an early sales call,

the trainer for the Indianapolis Colts agreed to hear him out.

He entered a room with the entire training staff for the team. “You’ve got five minutes,” someone said. “Go.”

Much of the work throughout late 2016 and 2017 was trial and error. Reaching athletes via social media, making short video clips, learning that it doesn’t matter how big an athlete’s bank account, he likely won’t pass up a free custom-designed product.

Now Kramer doubles his time as marketer/salesman and engineer. He tinkers with the product. If athletes and training staffs complain, the inventor-engineer combo of Arciuolo and Kramer figure out ways to make VKTRY better.

Old-fashioned word of mouth and shoe leather also worked, expanding VKTRY’s client roster. Today, athletes on 80 NCAA teams and 70 pro teams across all sports wear the insoles. Recently, the company inked a deal with Josh Norman, star cornerback of the Washington Redskins, to promote VKTRY.

But the bulk of sales are to amateur and high school athletes. That’s by design, and it’s where the company’s future lies.

There are roughly 35,000 professional athletes in the U.S. Across all divisions, there are about 250,000 college athletes.

There are 1 million high school football players in America. That’s football, alone. A 1 percent penetration into the amateur and high school market could mean $85 million in sales for VKTRY.

Something Old, Something New

Up until his senior year, Kramer thought his job as a student at Lafayette was to memorize equations to apply to engineering tasks.

The engineering program teaches you to just figure things out. And it’s not restricted to math or science. You can solve financial problems. You can solve marketing questions. It’s just like relentlessly trying things, testing them, optimizing them.

It wasn’t until his senior year that he realized what teachers like Hummel were trying to get him to learn.

“The engineering program teaches you to just figure things out,” he says. “And it’s not restricted to math or science. You can solve financial problems. You can solve marketing questions. It’s just like relentlessly trying things, testing them, optimizing them. It’s a lot of what the engineering division teaches.”

For every success at VKTRY, there are failures. Kramer has learned the touchy-feely world of internet marketing through endless trial and error. Some athletes respond to Instagram posts. Some coaches are open to change. Sports agents are the ultimate salesmen. Selling them? It doesn’t get tougher than that.

But while VKTRY has forced Kramer’s versatile side, one core belief remains as strong as carbon fiber—his belief in what he’s selling.

Part of why Kramer works as a salesman is precisely because he isn’t one. On a sales call, he doesn’t offer gimmicks. In the midst of the fast-talking, white-knuckle world of big goals and bigger promises, Kramer talks about how the product he helped build was developed and what it can do.

“I’m not a salesman,” Kramer tells them. “I’m the engineer. We developed this. Here’s how it works. Are you going to buy it or what?”

“And for some reason,” he says, “that works.”