Over There, Over Here

When the U.S. declared war on Germany on April 2, 1917, Lafayette’s campus sprang into action.

Almost immediately, everyone tried to play roles in the war effort. Prof. Edwin O. Fitch, a naval reserve officer, helped students learn military drills, using pool cues and broomsticks in place of actual weapons. The College’s technical faculty became a branch of the National Research Council and offered “to make such applications of science as would promote the national security of welfare.” The College offered its mechanical engineering facilities for the production of munitions. (Nobody took it up on the offer.)

More than a third of the graduating class volunteered to serve in the military. The College agreed to confer degrees on many of them early; others were invited back to finish their coursework when the fighting was over.

In May 1917, the College had its first wartime commencement since the Civil War. Gen. Peyton C. March 1884, son of world-renowned English and classics professor Francis March, was at the ceremony, where he received a commemorative sword from the city of Easton and an honorary degree from the College. His son, Peyton March Jr., was a student who had volunteered for military service. A year later, the elder Peyton March would be promoted to chief of staff of the U.S. Army. His son would be dead—killed when his plane crashed during his training as an aviator.

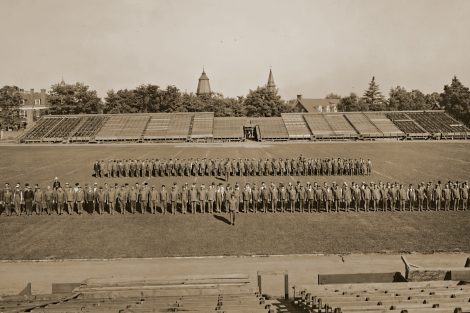

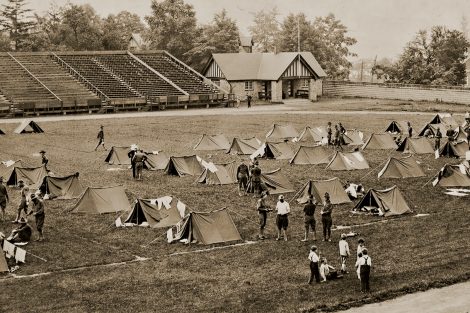

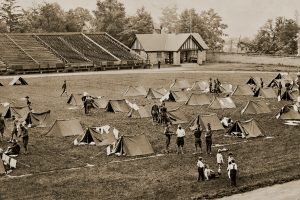

A few days after that commencement, Lafayette stopped being a college. It became Camp Lafayette—a special military camp for the duration of the war.

President John MacCracken had arranged with the U.S. War Department to provide a summer training camp for men who wanted to learn military mechanical trades—blacksmithing, electrical work, locomotive engineering, and driving.

Four-hundred men, mostly draftees with elementary school educations, arrived, along with officers, uniforms, and equipment. They trained on Lafayette’s campus and in other places around the Lehigh Valley, lived in dorm rooms, and ate in mess rooms established in the chapel and west wing of South College.

By August 1917, the first group had completed its training and shipped out to larger camps in Pennsylvania. Four-hundred-twelve new men arrived on its heels, and another group came in October.

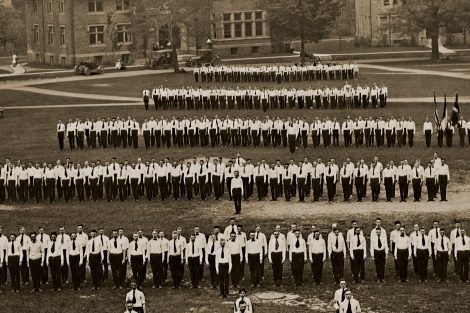

During the summer months, colleges across the U.S. and the War Department established the Student Army Training Corps (SATC). Enrollment at civilian higher education institutions was dwindling during the conflict. The plan was to train 120,000 men as soldiers who might otherwise have enrolled in college.

At Lafayette, 579 SATC service members were inducted, including 60 members for the Navy. The vocational unit was also still on campus, bringing the total number of men here to 1,100.

Cots filled the gym, and fraternity houses and dorms became barracks. Student-soldiers were posted as guards at the entries, and passes were issued for students leaving campus. At the beginning of each class, pupils snapped to attention and remained that way until their professors said, “At rest.”

Cots filled the gym, and fraternity houses and dorms became barracks. Student-soldiers were posted as guards at the entries, and passes were issued for students leaving campus. At the beginning of each class, pupils snapped to attention and remained that way until their professors said, “At rest.”

That fall, Lafayette fell victim to Spanish flu, the worldwide pandemic responsible for 50 million to 100 million deaths—3 to 5 percent of the world’s population. It blazed through College Hill in fall 1918. At its peak, 140 men were bedridden, and the Phi Gamma Delta and Delta Upsilon fraternity houses were converted to hospitals. Five men died.

On Nov. 11, 1918, when the German government signed an armistice agreement with the Allied powers, the camp quickly demobilized. On Dec. 7, 1918, soldiers marched through the streets of Easton, abandoning the camp for good.

On Jan. 2, 1919, Lafayette reopened as a college. Four-hundred-sixty-two students returned, and regular courses were re-established.

Too Many Sad Things I Saw! Too Many! Too Many!

Kenneth F. Kressler in 1918 in his uniform

It began with bayonets and armies marching in columns, but by the time Ken Farrington Kressler 1918 got there the Great War had changed.

Now, technology held sway. Bearlike machines called tanks rumbled through European battlefields. Planes worried the skies over France. Machine guns mowed down entire platoons. The military issued masks to protect soldiers from gas attacks. Trenches furrowed the ground in eastern France and Belgium, and in them men stared at one another over endless miles of corpse-strewn battlefields.

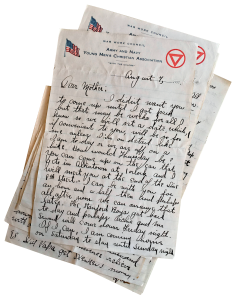

Kressler was 22 when he arrived as part of a Lafayette College Ambulance Corps attached to the French army. Through a lens of almost unflinching optimism, he witnessed the worst of the 20th century, reporting in carefully calibrated detail in the dozens of letters he wrote to his family. He wrote whenever he could find time, often in the wee hours by candlelight, in army barracks, trenches, and bombed-out chateaus.

The handwritten letters are preserved at Skillman Library. One-hundred years later, they give a unique and immediate view of the first World War.

During his year of living in the streets and countrysides of war-torn Europe, Kressler becomes a man, revealing through his candid and literate writing the hope and strength of his generation.

Forwarding Human Progress

Kressler was in the final months of his junior year when President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany on April 2, 1917. By then, the war had raged in much of the rest of the world for three years. Millions had died.

Lafayette students joined the march “over there.” Before the end of the term, 146 students had left, 38 of them seniors who hadn’t stayed to graduate. A parade of 20 Lafayette men marched to the train on May 11, led by the college president, members of the Board of Trustees, and faculty.

That summer, it was announced that the U.S. Army Ambulance Corps would have a unit made up from Lafayette College. Thirty-six men were requested to join. After talking it over with his family, Kressler, who’d lived his whole life in Easton, joined up. It meant delaying his graduation.

They trained in Allentown at the fairgrounds and at nearby Tobyhanna. For the summer and fall of 1917, Kressler’s letters spoke light heartedly of life in the camp. The war, and the increasing likelihood of his going to it, is a dark form in the corner of the picture.

United States Ambulance Corps

Allentown, Pennsylvania | (Undated)

Dear Mother and Father:

I was examined and sworn in the Army Ambulance Corps on Saturday afternoon. Much confusion prevails as far as details are concerned in everything. The different steps which we three fellows, Kline, Evans and myself, will have had to go thru before we become part of the Lafayette unit are too numerous to mention. We expect to become finally settled tomorrow morning … it becomes obvious that much red tape exists in this encampment of three thousands of men and boys, for most of us are boys.

… we are members of a part of what I believe will become the greatest military organizations ever assembled together for the forwarding of human progress.

There are a few conditions distasteful, the toilets and the bathroom facilities, there being the drainage for the sewage and only 2 baths.

… but you wipe them off on your trousers and dig in much like the pigs in whose former pens the Lafayette unit is now quartered.

December

From all indications we are going to leave in the forepart of next week. I hope we go this trip for it sure does ‘get one’ to remain in the unsettled state that we have been in during the past four months.

Did you read President Wilson’s speech printed in today’s papers? It was a masterpiece don’t you think? If the policies which he outlined there in regard to a permanent peace are carried out I don’t believe this war will have been fought in vain. The sorrow and suffering will in time pass away. The principles for which those who are suffering and dying fought for will endure thru the generations. It is a wonderful thing that each one of us

can play a part in this great world change.

Dec. 23, 1917

Dear Mother and Father:

You have received my telegram by this time. The orders to move came at 3.30 o’clock. I know it is useless to ask you not to worry over me. It is no time for an overflow of sentiment. Both you and I know full well what it means to the other to go out into the night at this season of the year, but the same great power which enables us to understand and appreciate the other’s feeling will give us strength to bear up under any adverse circumstances. Don’t worry over my material comfort. I am well equipped in clothing of all kind. If for three years I have had doubts as to the reality of a living God, I have none now. For the past six months I have gradually been forced to admit that my doubts were the result of ignorance. What I am about to go thru will only strengthen my faith. I need not ask you for your prayers. I know I have them. Worry not over my spirit. … When temptation would assail my morals, I will as I always do think of both of you. If you have a failing they but make your goodnesses great by contrast; it places you in that class of people who as the poet says “are not too good for human nature’s daily food.” To some temptation I may fall. Two that you need not fear are gambling and drinking. As for women, I have kept clean thus far in life and I hardly think that I am likely to succumb to the great lure at this stage of the game.

Thousands of men wouldn’t write to their parents in this vein at a moment like this. …The trucks are grumbling outside the barracks door, waiting, waiting to be loaded with our barracks bags.

Enjoy your Christmas holiday. I’ll be with you in spirit and that, if not in person.

Write to me after I send the letters for instructions.

I have said what I wanted to say if not in the way I desired to say it.

A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to all,

Ken

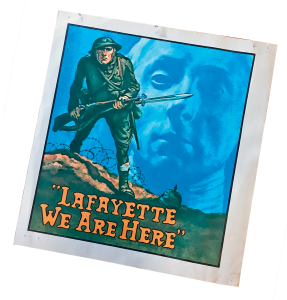

On July 4, 1917, a U.S battalion marched into Pipcus Cemetery in Paris to celebrate July 4—part of a display of unity with France. The U.S. had entered World War I just three months earlier.

The tomb of the Marquis de Lafayette, hero of the American Revolution, is in Pipcus. U.S. Army Col. Charles Stanton stood before the grave and placed an American flag upon it.

“The fact cannot be forgotten that your nation was our friend when America was struggling for existence, when a handful of brave and patriotic people were determined to uphold the rights their Creator gave them,” Stanton said in his speech, “that France in the person of Lafayette came to our aid in words and deed. It would be ingratitude not to remember this, and America defaults no obligation … Therefore it is with loving pride we drape the colors in tribute of respect to this citizen of your great Republic, and here and now in the shadow of the illustrious dead we pledge our hearts and our honor in carrying this war to successful issue.”

“Lafayette,” Stanton added, “we are here.”

The last words became an American motto during the war and appeared on posters and propaganda. France was home to many of the war’s greatest horrors, and both nations were eager to show solidarity. The affection continued throughout the war as Americans and French fought side by side in the trenches.

Somewhere in France

The Lafayette Ambulance Unit, Section 61, sailed from Hoboken, N.J.,

for France on Christmas night, 1917. German U-boats worked to create

a blockade in the northern Atlantic.

New Years Day | ‘Somewheres’

Since we left an American port six days ago for ‘Somewhere in France’, this is the first time I have started to put my thoughts and those of my observations which I am allowed to, on paper.

… [After dinner on Dec. 23] … We had two or three hours to wait, during which time, some sang in low voices, still others laid upon their bunks sleeping and dreaming of the past. I went over the past, leaving out only the unpleasant things, from the time when I first noticed things and people up to that very night. Only occasionally did I glance about to see what others were doing.

It is now 11:45 at night, and the order to launch has come. We launch, put on our packs and the moment for which most of us had waited for six months had actually arrived.

… It behooves every man to observe strictly the cautions which are taken to prevent the enemy from getting on our course. The light from a cigarette can be seen from a distance sufficient for a submarine to approach without being detected. Every man must keep his life belt continually with him. Loud singing at night is prohibited because noise carries a great distance on the water. The weather is still warm, and as Isadore Exodus Cohen says “We’re enjoying the $200 free trip to the limit.” He fails to say what the limit is.

… All the Lafayette boys are well.

Somewhere in France | I don’t know where in Europe

Dear Parents:

Arrived safely. Will be a few weeks before you again hear from me. I’m Best of health and spirits. Of necessity, I must be brief.

Don’t worry.

Love to all,

Ken

Shortly after landing, the Lafayette Unit disbanded and its members dispersed among other Ambulance Corps throughout France. Kressler was attached to Section 643. When Kressler reached them, they were en repo, or assigned to duties in the rear, at Savonnieres near Versailles.

Jan. 22, 1917 | “Somewhere in France”

Dear Mother and Father:

I have been assigned to permanent section doing duty at the front. … The old Lafayette Section is shot to pieces. Kline is the only one of the old crowd left with me.

A View of Hell

Kressler’s section spent two months on the right bank of the Meuse doing line work for the 20th Division.

April 16

Dear Mother:

The reason I do not write you about my troubles is because I haven’t any. It is something for which I am not looking just now and what is more I am a firm believer, as long as this war is on, in the little phrase “never trouble trouble and trouble won’t trouble you.”

April 17, 1918 | France | Letter No. 44

Dear Father,

… I was out to Post yesterday and last night, and while talking with one of the stretcher-bearers, it occurred to me that it would interest you to know something about these brave men …

Most generally, the stretcher bearers are recruited from that class of men between the ages of thirty-five and forty-five. They come from all walks of life: I personally have met a sculptor, a farmer, a poet, a priest, a wagon builder, a dry-goods merchant and what not. Several qualities are common to them all: They are usually very powerful men and not a few of their number are in the “six footer” class; they seem to have a more or less set group of questions which they ask one: they are generous, being willing to share anything they possess with one; as far as I can observe they are kind and considerate, one to the other. The manner and spirit with which they conduct themselves is worthy of emulation. I care not what the motive in back of it is, whether they are forced to be what they are or not, their courage, their devotions to duty, has reached that stage where mere words but cheapen the qualities they otherwise would glorify. There is no game like war to bring it out in such a startling manner, the noblest and basest qualities of a man’s nature.

The stretcher-bearer goes forth into “No Man’s Land” with the hand grenade throwers and the man with the rifle and bayonet. When the charge is over, he it is who carries the hacked and mutilated bodies of his comrades to a little abri in the front line trench, there to be given first aid treatment. From here to our post a mile or even two behind the lines, these stretcher bearers carry the wounded. Truly theirs are deeds of mercy. They possess nothing with which to defend themselves, and while they are not fired upon deliberately, never-the-less, their death rate is among the highest, if not the highest in the service.

Friday afternoon | Personal

Dear mother,

… One can ill afford to give way to any moments of despair when he notices the heroic and sublime manner in which the French Solider goes about his daily task. Even tho the days be dreary try to look at the bright side of everything. Do my duty, read, plan for the future: If I stray off my path I recall the real suffering that thousands yea millions of my fellow man are enduring and I admit to myself there is no reason for looking at the mud when by lifting my eyes I can see the shining heavens.

April 21, 1918 | Sunday Evening 9.30 P.M. | At Post

Dear Father:

… When we arrived at the post, we found things rather quiet and we took advantage of Fritz’s day off and for two hours wandered over a part of one of the most tragic and sanguinary hell holes the Earth’s face has ever been scarred with. Awfulness in its true meaning is the only word which can describe it. And this opinion is not given after the first sight of a modern battlefield, but after being at the front for over a month. If I should endeavor to give you a picture of what I saw in those two hours and a day [and] by a super-mastery of words succeed in my endeavor I would give you a picture of the inside of hell, and I am just a common soldier with no desire to challenge the greatness of Dante.

When we got back to the post, we read for a few hours until dinner, which consisted of stewed beef and bread. … The four brancardies (stretcher bearers) and the young French Doctor who dwell in this underground place are as likeable a group of men as one could find anywhere, and to me it is ever a source of happiness to give them anything I can.

When we got back to the post, we read for a few hours until dinner, which consisted of stewed beef and bread. … The four brancardies (stretcher bearers) and the young French Doctor who dwell in this underground place are as likeable a group of men as one could find anywhere, and to me it is ever a source of happiness to give them anything I can.

One of the number … went out in the shell holes this morning and picked for me a bunch of violets and tied a little red, white and blue ribbon around them. These together with a sacred heart bunting which he gave me tonight I am going to mail to you tomorrow in a separate envelope.

These men also found out I liked dandelion, so they again visited some surrounding shell holes and got us a fine mess of dandelion for supper.

In the afternoon, we went around the hill looking at different cannons and shells and just let me state here that the more I see of these French the more I am convinced that I would much rather have them with me than against me. You cannot beat someone who is unbeatable and the French can never be conquered.

… The graveyard of which I speak is one of thousands which dot the hillsides of France. These graveyards are about as large as the ground around our home. Little wooden crosses mark the last resting place of many an heroic soul. If the soldier had not been mutilated too badly to obscure his identity, his name, when he died, and to which division he belonged, it is printed on a round piece of tin about 5 inches in diameter and nailed with the colors of his country on the little wooden cross. If his identity is not known just a simple inscription “Soldat Francais” is marked on his cross. Just a Soldier of France!

Often times, an “in case of death letter” is found on a dead soldier and this letter is put in a bottle and placed over his grave for his relatives to get after the war.

Not occasionally but often in this sector a great German shell will land in the center of one of these graveyards and all that is left are a few broken crosses and human bones. A shell, depending on its size, will make a hole as large as an ordinary room … to one so large that our home could be placed in it if it were square instead of cone shaped.

May 22 1918 | France

Dearest Mother:

… Oh mother, why must men fight when there is such great joy and happiness to be derived from communing with nature? There is happiness for the asking, yet we choose war, and some people call it the “War Beautiful”: It may be; yet ask the wives, the mothers, the children of these hundreds of thousands of soldiers who are sleeping their last sleep beneath the little black crosses which dot the hillsides of France and see whether they think it is a war beautiful. Too often in life do we judge things from one angle. We do not take the time to observe the thing in its entirety. It may be that my vision of war’s greatness is narrow. If it is, I pray God to enlarge and make greater that vision.

The Retreat

While at rest at Ligny en Barrios, the 20th Division and Kressler’s section were

ordered north to block a gap the Germans had made on Allied lines on Chemin des Dames. Later, they were ordered to fall back. For two days, they retreated until they crossed the Marne.

France

Dear Mother:

… Yesterday, one week ago, after being on Repos for a week, we left for one of the active fronts. We traveled until one o’clock the following morning, put up in an old barn until six A.M. after which we again started our cars on their journey. We went to a certain village where at we stayed until 1 o’clock that afternoon. At that time the Boche started to come across the opposite hills and we started to make a retreat along with all other sensible people.

That afternoon and the days following I shall never forget. About the general war situation, you know more than I, for we have been unable to buy any newspapers. That phase of the retreat which I wish most to write about—the refugees along the road—I am allowed to so do. However I am on first call this afternoon … This is just a little message to relieve you of any anxiety concerning my welfare. I am well and aside from being just a little tired from want of sleep am as fit as a dollar.

June 5, 1918 | France

Dear Mother:

… I said I would tell you of one of the most pathetic and sorrowful sights I have ever seen—the refugees who thronged the highways in the district where I am now working during the first few days of our retreat.

Our section was running along in a convoy on May 28th about one o’clock in the morning when these people who have been routed from their homes and all that home means started to file past us with their homely rigs and the few simple things which they snatched up when they heard the hated Boche were coming. I can not describe the feeling of revulsion, which took possession of me, against the things which made such a sight possible when first I saw the vanguard of this saddened multitude. For two and one half days they plodded past as we drove back and forth from the lines to the hospitals with wounded soldiers.

Some had vehicles in which to move the articles most needed for their welfare, such as blankets, bread, etc., but mostly carts—drawn by horses, oxen, donkeys, and dogs. Some drove their cattle and sheep before them, more left them behind. Yes, these people left most everything behind them, all but hope; their gardens with their vegetables ready to be gathered …

But they go suffering in silence for their beloved France. Germany can never conquer French spirit. Like the hills it is eternal.

… the whole scene appeared to be a picture … something which could not

be real … oh so many sad things I saw! Too many! Too many!

Bells are ringing

For months, Kressler and his comrades continued to tend to the wounded and the dying.

In early November 1918 they took position for an expected drive against German positions

in Metz. On Nov. 11, the day of the armistice, the section was at Thaon-les-Vosges.

Nov. 11, 1918

Dear Bill:

Enclosed in this box you should find the helmet of which I wrote you, two gas masks and a French bullet pack. The stuff in the pack I got at Verdun last February, Lincoln’s birthday. The mask in the tin pan has been my good companion for many months. The other is the style used when I first came over. Both are French. …

TODAY THE ARMISTICE WAS SIGNED, KEN

(on the reverse side)

All is excitement, the bells are ringing the people are joyful. Four years and a half of hell ended. Oh Boy.

Nov. 11, 1918 | France

Dear Mother:

To-night my heart is filled with such thankfulness that I can well say with the poet, Tennyson

Break Break Break on thy cold gray stones o sea

And I would that my tongue could utter the thoughts

That arise in me

For surely never in my young and inexperienced life have such thoughts of joy, happiness, sorrow and what not taken hold of me so completely that they have left me without the power of expression. For today, dear mother, as you will know long before you receive this letter, the representatives of what is left of the German government signed the armistice which will bring peace to a distracted and war weary world. What this momentous event means to the mothers, the sisters, the children and the soldiers of all involved nations cannot be expressed by mere words.

Germany has been a cruel and relentless enemy. Her day of doom is at hand and it is the serious duty of the allies to see to it that the doom is sealed. Never again shall a powerful nation strike such a wanton blow at an unsuspecting world without full knowledge of the awful penalty [if] such an attack has as a sequel. Their inhuman methods of warfare: their maltreatment of defenseless women and helpless children, their wanton destruction of cathedrals and works of art, the landmarks links which connect the past and the present …

For the hundreds of thousands of soldiers who are sleeping their last sleep in the churned ground of the bloody battlefields of this war, for the maimed, for the sorrow of mothers and wives whose loved ones fell there is that great compensation which comes from fighting and winning a just and righteous cause. It is a pity that those who died could not have known that such a brilliant victory was to be ours.

I am justly proud of the part America has played. Who isn’t? Without her moral strength, without her food and money, without her magnificent army the allied world would not be celebrating victory today. President Wilson himself was worth as much to the cause as a whole army because of his gifted leadership. …

And I am glad too that I played a small, a very small part in this war. What I did is not what I wanted to do. I thought all along, still think, and always will think that under different circumstances I could have played a bigger part. But there are many other men who are far more able than I who will be mustered out with the rank they were given when they joined, a buck private. I tried to do my work, whether it was going out over a shelled road to bring in wounded or peeling potatoes in a manner which would give me no reason for regret when all was over. And therein lies my compensation. Now that it is all over you may be curious to know how I acted in tight places. There were times when I was afraid in a sense, I just can’t explain it, but my sense of fear was never sufficiently strong enough to overcome my sense of duty, that duty I owed to the wounded man who was doing the real fighting. And may I truthfully add that I do not know of a single case in our section where a man shunned his duty in order to [ensure] his personal safety. And some of the men were in far more dangerous places than I. I believe that one of the greatest factors in compelling men to carry on to the last is that desire that every red-blooded man has of doing nothing which would make life harder for the other fellow.

In the days that followed, the 20th Division, including Kressler’s section, made a procession behind the withdrawing Germans and was the first to reach the Rhine.

Nov. 25, 1918

… It was on the early afternoon of Nov. 15th that we crossed “no man’s land.” Before the vanguard of our division went over these lines it had been four years and more since any man could show his head here without the dangers of having it disengaged from the rest of his anatomy. Not many kilometers from where we crossed the lines we crossed what was once the French and German Frontier … It was a cold dull November afternoon and a flurry of snow greeted us as we passed into this land, which for forty-eight years had waited for the French to deliver the from German Power.

… at nine o’clock in the morning the sidewalks were lined 6 to 12 deep with all manner and kind of people. For many, it was one of the greatest moments of their lives.

Kressler’s elation was short-lived. Early in 1919, he received word that his brother, William, had died in an industrial accident.He was awarded the Croix de Guerre for gallant action in the war. Before returning home, he attended the caucus in Paris where the American Legion was born.

Back home, he finished his coursework at Lafayette, obtaining a degree in philosophy. He later was an organizer and the first commander of the Brown and Lynch American Legion Post 9 in Easton.

He had a long career in finance as president of the insurance firm Kressler, Wolff, and Miller, served two terms on Easton City Council, and was president of Easton Area Chamber of Commerce. A constant fundraiser and benefactor, Kressler helped found Friends of the Skillman Library in 1964.

He died on Sept. 22, 1966, at the age of 71.