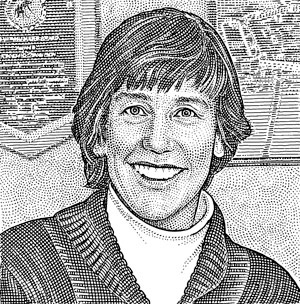

Vicki Thompson ’84 Controls Pests in Monmouth County

By Kevin Gray

MORE THAN 100 years ago, the New Jersey legislature passed laws creating mosquito-control commissions, mandating that county governments fund them and empower them to eliminate mosquitoes and their breeding areas. The measures were taken after the discovery that mosquitoes transmit malaria, yellow fever, and encephalitis.

On the front line of the battle to control the mosquito population in Monmouth County is Vicki (Crouse) Thompson ’84. She is assistant superintendent of Monmouth’s Mosquito Extermination Commission, established in 1914 to protect residents and visitors from arthropod-borne diseases while maintaining an environmental comfort level suitable for enjoying outdoor activities.

More than 30 mosquito species are in Monmouth County, Thompson says, including some that globalization has brought recently. The population of the Asian tiger mosquito, discovered in the county in 1995, has exploded.

More than 30 mosquito species are in Monmouth County, Thompson says, including some that globalization has brought recently. The population of the Asian tiger mosquito, discovered in the county in 1995, has exploded.

“It has become the biggest nuisance mosquito in the county. This species can develop in as little water as that held in a large water bottle cap or a plastic candy wrapper. And it’s difficult to control,” she says. “We’ve also had West Nile virus in birds, mosquitoes, horses, and humans since 1999. Last year was very active for West Nile virus.” New Jersey also has experienced outbreaks of St. Louis encephalitis and Eastern equine encephalitis and the reappearance of malaria in 1991.

All mosquitoes rely on water for part of the life cycle. Some species lay eggs on the surface of permanent water, others at the edge of a spot that floods with rain, such as a large puddle or temporary pond in the woods. Successful mosquito control depends on knowing which species are locally important as vectors of disease, where the breeding sites for those species are located, when the adults will emerge, and what control measures are most effective with the least disruption to the environment.

“We use an integrated pest-management approach that focuses on controlling mosquito larvae vs. broad control of adult mosquitoes,” Thompson says. “Much of our effort involves source control — reducing or eliminating standing water where mosquito larvae flourish.” Other methods of control, such as introducing fish that eat mosquito larvae and cleaning streams to improve water flow, also are used.

Thompson, who has been with the commission since 1996, oversees day-to-day operations, particularly water-management projects. She has become a leader for regulatory compliance for wetlands, flood hazard areas, pesticide, solid waste/hazardous waste, and safety regulations.

Clearing stream sides of debris and trash eliminates pockets where water can become stagnant and improves stream flow — both actions that help with mosquito control. “At a watershed meeting, the chair talked about the condition of a stream and compared two sections. One was pristine, natural, sinuous, lined with plants and overhanging vegetation. The other was full of debris, trash, and sediment. He did not know it at the time, but we had cleaned the ‘natural’ section the year before. I felt proud of our work,” Thompson says.

In 2005, she received the Jessie B. Leslie Award for meritorious service presented by the Associated Executives of Mosquito Control Work in New Jersey. In 2010, she received the New Jersey Mosquito Control Association’s Bunnie Hajek Award. A geology graduate who also holds a master’s from the University of Delaware’s College of Marine Studies, Thompson credits Lafayette for giving her a solid base in science.

“Geology combines aspects of biology, chemistry, physics, and history. This broad view taught me to look at situations from multiple points of view and disciplines. I never imagined I would land where I am now,” she adds. “As a kid, I loved playing with water and mud. Now, I get paid to do it.”