The Pursuit of Beauty

By Stevie O.Daniels

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863–1923) Louis Comfort Tiffany 1911. Oil on canvas, Tiffany in the garden at Laurelton Hall Courtesy of The Hispanic Society of America, New York

Louis Comfort Tiffany was one of the greatest designers of all times. He was a magical craftsman who conjured beauty and pushed artistic boundaries in many forms, including jewelry, mosaic, painting, and pottery. He also revolutionized the art of stained glass, creating exquisite lamps and windows that brighten the world’s most prominent museums, churches, banks, hospitals, and landmark buildings, including those at Lafayette College.

Tiffany’s link to the College extends beyond the two glass windows that now reside in Skillman Library. In 1886, he married Louise Wakeman Knox, the daughter of Lafayette’s president at the time. The couple was married for 18 years before Louise died, but from a creative and commercial standpoint, Tiffany’s most productive period was during their time together. His designs remain as enthralling and desirable today as they did more than a century ago, and this spring, a trio of exhibitions, with associated programs and an exhibition catalog, celebrate the legacy.

Who was Louis Comfort Tiffany?

Louis Comfort Tiffany was one of the most creative and prolific designers of the late 19th century, among the first American designers to be acclaimed abroad. His life goal, he said, was the “pursuit of beauty.”

The inheritor of the Tiffany & Co. kingdom from his father, Charles Louis Tiffany, Tiffany was, first and foremost, a painter who began experimenting with the chemistry and techniques of stained glass in the 1870s. He developed this interest while establishing the company as a premier interior decorating firm. His clients included Cornelius Vanderbilt II; Mark Twain in Hartford, Conn.; and the White House during President Chester Arthur’s administration.

By 1880, Tiffany had registered a patent for opalescent window glass, a new treatment in which colors were combined and manipulated to create an unprecedented range of hues and three-dimensional effects. He called his glass “favrile,” loosely derived from the Latin fabrilis, “made by hand.”

Molly-Polly Chunker

In 1886, Louis Comfort Tiffany, a socially prominent New York artist and creator of the famous Tiffany stained glass craft, was a 38-year-old widower whose wife had died two years earlier, leaving him to care for their three young children. He was courting Louise Wakeman Knox, friend and cousin of business partner Lockwood de Forest and his sister, Julia de Forest, and daughter of James H.M. Knox, eighth president of Lafayette College. In June, the two embarked on a two-week canal excursion in a rebuilt mule-drawn barge on the scenic Delaware and Lehigh canals from Bristol to Mauch Chunk for the “purpose of photography.” The arrangement was a good one as chaperones often sighted the pair “developing film” in the enclosed dark room. Henry Holt served as scribe for the expedition and kept most of the log. Before arranging the limited, private printing of the log in 1887, he made revisions to the entries and added most of the references to the 68 remaining photographs from the total of 600 glass plates that had been used.

In 1886, Louis Comfort Tiffany, a socially prominent New York artist and creator of the famous Tiffany stained glass craft, was a 38-year-old widower whose wife had died two years earlier, leaving him to care for their three young children. He was courting Louise Wakeman Knox, friend and cousin of business partner Lockwood de Forest and his sister, Julia de Forest, and daughter of James H.M. Knox, eighth president of Lafayette College. In June, the two embarked on a two-week canal excursion in a rebuilt mule-drawn barge on the scenic Delaware and Lehigh canals from Bristol to Mauch Chunk for the “purpose of photography.” The arrangement was a good one as chaperones often sighted the pair “developing film” in the enclosed dark room. Henry Holt served as scribe for the expedition and kept most of the log. Before arranging the limited, private printing of the log in 1887, he made revisions to the entries and added most of the references to the 68 remaining photographs from the total of 600 glass plates that had been used.

The barge was a rebuilt gravel carrier of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, but it was hardly recognizable in its newly resplendent form. It had a roof, promenade deck, and black and yellow canvas side-projecting drapes. The interior included a kitchen, saloon, dining room, and three sleeping rooms, and was staffed by a cook, butler, and other servants.

The travelers, knowing that boats going to Mauch Chunk were called Chunkers and the names of the mules drawing theirs were Molly and Polly, christened the “ship” Molly-Polly Chunker.

Five months after the voyage on June 21, Louis and Louise were married in New York City. The bride’s father, a Presbyterian minister, officiated. The couple had twins, Julia and Comfort, who were referred to as “the Tiffany Vanilla and Strawberry Twins” because they were dressed in white and pink outfits to distinguish between them. They also had a daughter Dorothy, who became a lifelong companion to Anna Freud, Sigmund Freud’s daughter.

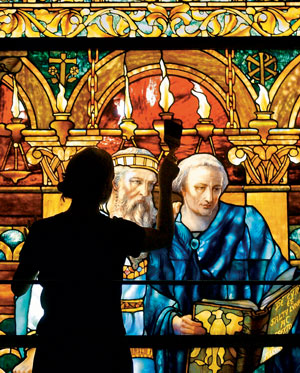

Alcuin and Charlemagne

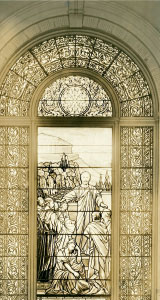

Sarah Monte, a talented colorist and glass artisan, conducts a final inspection in the Willet “viewing room,” which has a 24- by-24-foot plate glass exterior window. Restored windows are viewed in natural light to better replicate the conditions in their final location so that the window’s overall continuity can be assessed.

The first Tiffany window installed at Lafayette was commissioned for Pardee Hall at a cost of $1,625. The arch-topped, 14-foot-high window commemorates the friendship between Ario Pardee, the College’s first great benefactor, whose gifts established the engineering program (1866) and funded Pardee Hall, and William C. Cattell, president of the College from 1863 to 1883, by picturing a famous parallel from medieval history—Charlemagne and Alcuin.

Charlemagne was the patron for English cleric Alcuin of York, shown on the right in his long blue robe. Alcuin was invited by Charlemagne to his court in Aachen where the scholar established a Palace School attended by Charlemagne, who was attempting to learn to read and write. Charlemagne has one hand resting on Alcuin’s shoulder and the other on a book on the table beside him, labeled Baeda, the great Anglo-Saxon scholar whose works had inspired Alcuin. They are consulting an astronomical textbook of which Alcuin was the author. A row of seven flaming lamps above the heads of the two figures represents the seven branches of learning that Alcuin introduced to Charlemagne’s court. Both men were well-known in the late 19th century. Alcuin’s importance as a teacher and as codifier of the tenets of liberal arts made him a central figure in educational circles.

Designed by Frederick Wilson, who became head of Tiffany’s ecclesiastical department, the window was installed in front of the second-floor auditorium above the center of the stage.

There, it was used to teach Lafayette students sitting in the auditorium about the roots of liberal education. It also honored two major figures in Lafayette’s own history who had made such learning available to modern generations.

The Death of Sir Philip Sidney

The suite of windows titled The Death of Sir Philip Sidney—a central pictorial panel and two flanking ones—was ordered from Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company in 1899 for the main reading room of the new Van Wickle Memorial Library and installed in the large west window by 1900. Also designed by Frederick Wilson, this window’s central character, Sir Philip Sidney (1554–86), was a poet and one of Queen Elizabeth I’s favorite courtiers.

The scene is a battlefield at Zutphen in central Netherlands where Sir Philip had gone to aid his uncle in attempting to capture the city from the Spanish during the Dutch wars for independence. The background is filled with marching soldiers, wagons, horses, and a flag with a Tudor rose.

There are several focal points: Sir Philip and his broken leg, the drink that Sir Philip is rejecting, and the foot soldier who is to receive the cup instead. To negotiate the complex story line, Wilson created an elaborate multi-figured composition comprising a series of interrelated triangular groupings. The seated figure of Sir Philip forms the base of the primary triangle. He occupies the left foreground, his legs outstretched, one leg bent at the knee with the trouser rolled back and a tourniquet around his wounded thigh. A soldier in full armor bends toward him holding out a cup, and a third soldier forms the apex of the triangle. A kneeling figure at the center bandages Sir Philip’s wound. The story depicted was first told by Sidney’s close friend, Fulke Greville, Lord Brooke, in The Life of the Renowned Sir Philip Sidney (1652). Sir Philip did not wear leg armor on the day of the battle and received a musket shot that broke a bone in his thigh. He called for water, which was brought to him, but when he saw a wounded soldier being carried by, he gave it to him and said, “Thy necessity is greater than mine.” The awareness of Sir Philip Sidney as a poet and hero was widespread during the 19th century, and his work was part of the literary canon for university students.

He was frequently cited in instruction manuals on good behavior and as a model in guides for youth on how to conduct themselves in life. The window, prominently placed in the reading room, was an instructional model of moral guidance to the young men of Lafayette studying in its shadow.

Lost

Lafayette’s two other Tiffany windows—Ascension of Christ given as a memorial in 1912, and St. Paul Preaching on Mars Hill donated in 1916—were destroyed when fire gutted the interior of John Milton Colton Memorial Chapel in 1965.

The first was given as a memorial to one of Lafayette’s most popular professors, Augustus Alexis Bloombergh, and the second by Mr. and Mrs. S. W. Colton in memory of Mr. Colton’s father, Sabin Woolworth Colton, and his uncle, John Milton Colton.

By the mid-1960s, Alcuin and Charlemagne had been permanently removed from Pardee Hall, and Sir Philip Sidney had been moved to a less prominent location within Van Wickle.

Found

By the 1980s, the future of the two surviving Tiffany masterpieces did not look promising. Both windows were in Van Wickle Hall. The Sir Philip Sidney window was still visible, but only partially so because it had been bisected by a partition to create two offices. The Alcuin and Charlemagne was in the recesses of the basement in four crates. Without the intervention of E. Crosby Willet ’50, president and owner of Willet Stained Glass Studios, Philadelphia, the Alcuin and Charlemagne might have languished in storage. The window had been reported lost by Tiffany scholars and Lafayette administrators alike.

Restoration

Funding for the restoration of the Alcuin and Charlemagne and Sir Sidney windows came from Crosby Willet’s classmate William W. Lanigan ’52, an emeritus trustee and member of Friends of Skillman Library council.

Tiffany windows are typically of complex construction. More often than not, he employed many layers of various types of glass to create his painterly effects. Unlike the traditional stained-glass fabrication in which one layer of glass is neatly held in place by a matrix of lead channels between each piece, Tiffany’s layers of glass required new techniques of fabrication.

These wonderfully complicated techniques must all be identified, cataloged, and reproduced in order to faithfully restore a Tiffany window to its original glory.

The first step in the restoration process was to take photographs documenting the complex shapes, lead channels, and unique techniques for layering glass. Next, using rag vellum and wax, rubbings were made to record the precise location of glass and lead in the original. The window was almost completely dismantled. Everything was cleaned, including both sides of glass in sections where three layers had been used. Extra finesse was used around painted areas—heads, hands, and feet—which were in excellent condition.

In 2004, both windows were installed in the renovated Skillman Library, their magnificence made visible again.

Exhibits at Lafayette

Tiffany Glass: Painting with Color and Light

Williams Center Gallery, March–June 4, 2016

Organized by the Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass in New York, the exhibition comprises windows, lamps, and a large selection of loose glass pieces that illustrate Tiffany’s masterful use of opalescent glass to achieve painterly results. These objects are some of the most iconic and celebrated of Tiffany’s works, chosen because they exemplify the rich and varied glass palette, sensitive color selection, and intricacy of design that was characteristic of Tiffany’s leaded-glass art.

Curated by Lindsy R. Parrott, Director, Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass, Queens, New York.

Exhibition made possible by the generous support of Ellen Kravet Burke, Lafayette Class of 1976, and Ray Burke, Lafayette Class of 1975, in honor of Mr. and Mrs. Larry Kravet, Floral Park, New York

From the Tiffany Studios, New York:Courtesy of the Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass, Queens, New York

The Perilous & Thrilling Adventures of the Good Ship Molly-Polly Chunker

Louise Knox with Molly and Polly, 1886, National Canal Museum

Lass Gallery, Skillman Library, February–July 2016

Photographs and excerpts from the log of the Molly-Polly Chunker offer a glimpse of the pre-wedding boating party of Louis Tiffany and Louise Knox and friends aboard a mule-drawn barge on Pennsylvania’s Delaware and Lehigh Canals from Bristol to Mauch Chunk in 1886.

Images courtesy of the National Canal Museum, an affiliate of the Delaware and Lehigh National Heritage Corridor, Easton, Pennsylvania

Exhibition made possible by the generous support of Philip D. Wolfe, Lafayette Class of 1957

The Tiffany Legacy at Lafayette

Presentation copy of The Art Work of Louis C. Tiffany (Doubleday, Garden City, New York, 1914), signed by Tiffany Rare Books, Special Collections, Skillman Library, Lafayette College

Simon Room, Skillman Library, February–July 2016

Materials from the Lafayette Archives document the four Tiffany Studios windows owned by the College; the loss of two by fire; the restoration of the two now installed in Skillman; and the family connection to Tiffany, whose second wife, Louise Wakeman Knox, was the daughter of Lafayette President James Hall Mason Knox.

Exhibition made possible by the generous support of Stephen Parahus, Lafayette Class of 1984