Where did this 40-year hobby begin?

My lifelong interest in the history of speedway design and construction began with an independent study project I undertook as a senior at Lafayette in spring 1977. I had always been a race fan, so the idea of designing a superspeedway for my project was not too surprising.

My fantasy track, dubbed Keystone International Raceway, was based on the premise that “Pocono Raceway does not exist but remains a 1,025-acre spinach farm, earmarked for development into a multi-million-dollar superspeedway complex.”

The course involved a lot of effort but because it was something I enjoyed, it was more fun than work. The folks at Pocono Raceway were extremely helpful, especially Joe Mattioli III. Joe was the son of track owners Drs.Joe and Rose Mattioli and served as director of marketing at the time. He was also a fairly recent Lehigh graduate, so we naturally gave each other a hard time. Through Joe, I met the engineer who designed the speedway and general contractor who built it. And I got my first set of speedway blueprints.

On a whim, I looked up motorsports legend Mario Andretti in the Easton phone book and cold called him at his home. At the time, Mario was pursuing the World Driving championship (i.e., Formula 1) and was spending much of the late 1970s flying back and forth between his Nazareth, Pa., home and the rest of the world. I happened to catch him at home, and he gave 20 minutes of track design advice from a driver’s perspective to an unknown college student.

All this input ramped up my speedway design knowledge in a very short time. Combined with what I had learned in my civil engineering curriculum, I was able to put together a comprehensive product including a summary report, design calculations, and a set of manually drafted plans.

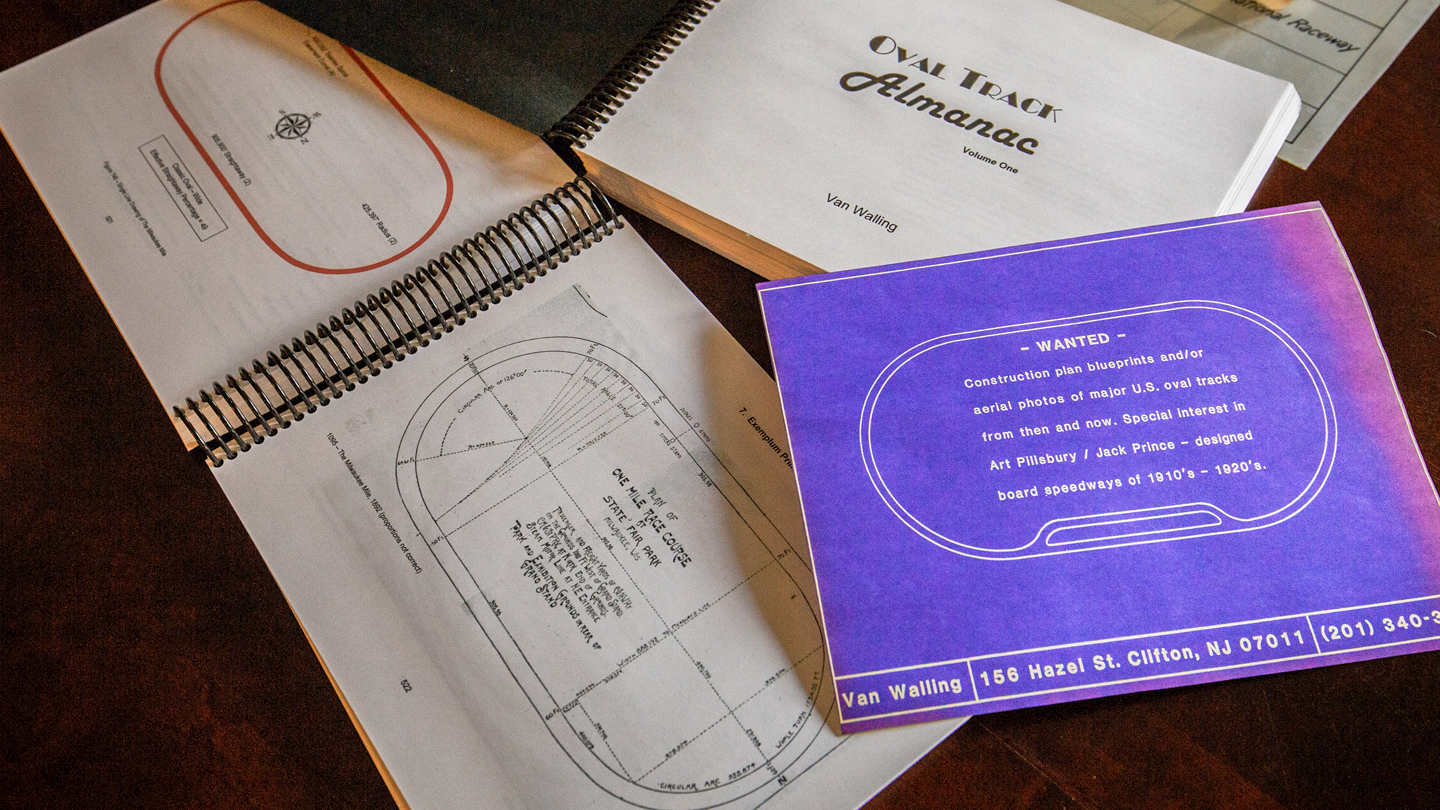

Very early on, I branded my efforts as Oval Track Almanac or OTA. The name has stuck and has been repurposed as the title of my book.

What is the typical process for finding material on a track?

In the pre-internet era, my research involved writing a lot of letters, making a lot of long-distance phone calls, and spending time at the library. It also meant a lot of dead ends.

Many of my inquiries went unanswered. The negative responses I received generally fell into two categories: 1) “We do not have the information you are looking for,” or 2) “The information you are seeking is proprietary.” These rejections only served to make the positive responses all the more gratifying.

For the last 20 years or so, I have been able to get most of my information online. It still takes a little bit of digging, no thanks to a certain gas station by the name of Speedway.

Also, my network has grown significantly through personal contacts, email, social media, “friend of a friend” connections, presentations, and media opportunities.

What are the different types of tracks you study?

Though I have limited my study to just oval tracks, I have over 900 tracks in my database. I have developed specific categories for my tracks; e.g., U.S. tracks that have hosted national championship races, tracks that are outside the U.S., automotive proving grounds and test tracks, but the main categories include actual tracks, ghost tracks, and paper raceways.

Many of the tracks are actual tracks from the past or present. Ghost tracks are a subset of this group. There are folks who are into checking out sites of former racing facilities, whether physical remnants remain evident or the site has a completely different land use, like a shopping center or industrial complex.

There are literally thousands of former racetracks that have passed into some sort of different land use over the years. Some are hiding in plain sight if you wanted to check them out on Google Earth or Maps.

Grand Boulevard in Corona, California, dates back to the late 1800s, and races were held there in 1913–14 and 1917. Not only is this 2.769-mile circle still visible, people still drive on it every day!

Urbano Drive in San Francisco, California, is a residential street that forms a 1-mile oval. From 1900-11 it was Ingleside Racetrack.

Likewise, Speedway Circle in Knoxville, Tennessee, is a residential street that forms a 1/2-mile oval. From 1915-20, it was Cal Johnson Racetrack, owned and operated by a successful African American businessman who was a former slave.

And my personal favorite, located in the western suburbs of Philadelphia, is West Chester Fairgrounds. It featured a 1/2-mile dirt oval that operated without distinction between 1923-37. Today it operates as Rolling Green Memorial Park with the former track serving as the cemetery’s oval-shaped perimeter roadway.

Paper raceways are oval tracks that were planned but never built, or in some cases, started but never completed. OTA contains nearly 500 paper raceways. This may be the only such database in existence; if not, then certainly the largest.

In the beginning, I had to search for paper raceways. I did lots of old-fashioned research, but nowadays paper raceways seem to find me. In other words, folks from my network will often forward a lead or supply a snippet of information.

For the engineers out there, let’s talk nitty-gritty: What makes for a good track?

OTA addresses this issue by defining 10 basic components associated with the three-dimensional geometric design of oval tracks: shape, length, area, orientation, straightaways, profile, width, banking, transitions, and surface. By reviewing these oval-track building blocks, OTA illustrates the myriad considerations and hidden complexity of each design component. This exercise gets even more complex when it is shown that many of the factors can be mutually exclusive, forcing difficult design compromises.

What are the common mistakes that engineers typically make?

Transitions are a simple concept—going from a relatively flat straightaway into a banked turn and out again—but it’s amazing how many designers and/or track builders have failed in this critical area over the years. Ramifications of poor transitions range from monetary (expenses of having to rebuild all or some of the track) to competitive (poor transitions often result in boring single-file racing) to safety (poor transitions can lead to accidents, injuries, or worse).

As a speedway design consultant, how many tracks have you helped design and build?

I have been involved in efforts regarding six or eight proposed speedways. None were ever built—in fact, none progressed past the conceptual design phase. At the time I was upset that none of the projects came to fruition, but with the benefit of hindsight, the reasons are very clear.

For one thing, the timing was not right for my involvement. Throughout the oval track generations, there have been a few droughts—extended periods when no new oval tracks were built. My involvement in the 1980s coincided with a dry spell the sport endured from 1971 to 1987.

Equally important is the fact that none of the projects involved the right individuals; i.e., those with the combination of business savvy, financial wherewithal, and motorsports industry connectivity.

Who are considered the design masters?

While there have been others, without a doubt, three individuals stand out for me as the masters of oval track design and construction: Jack Prince, Art Pillsbury, and Charles Moneypenny.

Prince was a former bicycle racing champion. Though not a trained engineer, he designed and built more than 100 velodromes, motordromes, and board speedways … and at least another 60 speedways that were never built (paper raceways). He is famed for his “triple radius” transition, a rather simple design element that he convinced the press was the magic ingredient in his tracks.

Pillsbury was a former city engineer for Beverly Hills and a long-time highly respected racing official. He partnered with Jack Prince to design and build most of the speedways of the 1920s. He is famed for his use of the Searles spiral easement curve, a transition used in railroad construction.

Moneypenny was a former city engineer for Daytona Beach. He designed Daytona International Speedway … working with engineers and mathematicians at Ford

and GM proving grounds to design the transitions needed for the high-banked speedway. He later developed and copyrighted the design of the D-shaped oval used at Michigan, Texas World, and Richmond speedways. He completed design of the latter facility in 1988 at the age of 92!

How big is your library of materials?

I have well over 2,000 electronic files, a couple dozen three-ring binders of correspondence, technical data, hundreds of photographs, more than 100 books, and a dozen or so speedway blueprints. The Darlington and Daytona blueprint copies are more special to me than rare in a collector sense.

I am also proud of the cards and letters I received from Bill France Sr. (NASCAR founder and builder of Daytona and Talladega speedways) and speedway designer Charles Moneypenny.

How many tracks have your visited?

Surprisingly, not that many. Maybe a couple dozen in person. And not always to attend a race … sometimes I visit a quiet racetrack. Growing up in New Jersey, I have many fond memories of going to the races with my father at Wall Stadium in Belmar and Trenton Speedway at the

old state fairgrounds. But I regret that we never made it to Flemington Speedway or Langhorne Speedway. Maybe he didn’t like dirt tracks.

Did your wife and kids like going on track mission trips?

Our family has been to many races together, but I can’t remember taking them along on a fact-finding trip. On a recent vacation to South Jersey with my wife, we first drove past a paper raceway site in Vincentown and later passed a ghost track in Hammonton known as Atlantic City Speedway, which amazingly is still visible (albeit barely) in aerial photos. I smiled as I motored by both locations, but kept on driving.

For the non-race fans, explain the beauty of a sport that seems to have folks driving in circles.

As much as auto racing means to me, I have never been one to espouse the virtues of my sport and try to convince others to become fans. I’m always reminded of the saying, “If I have to explain it, you’ll never understand.” While I am certainly not ashamed of my sport—or my rather unique area of interest within it—friends and fellow professionals are often surprised to learn of the depth and breadth of my motorsports involvement.

So what it comes down to for me is that I believe a person has to experience a race in person accompanied by an experienced race fan to answer the inevitable questions. Once the cars are on the track, it’s a sport that touches all the senses. That either works for you or not.

One memorable night during my sophomore year at Lafayette, a group of four friends and I went on a Saturday afternoon road trip. When I realized we were near Reading, Pa., I convinced the others that we should go to the regular weekly stock car races at the historic Reading Fairgrounds Speedway that night. I, of course, loved it, but my companions … well, let’s just say I wasn’t invited to join any subsequent road trips.

I recently began attending races at the local short track after an absence of several years. When I came home, my wife asked, “How were the races?” I replied that the racing was terrible … single file, very little passing, and too many caution periods. She said she was sorry I had such a bad time. I replied that I had a wonderful time. The sights, the sounds, the smells. It was as awesome as it has always been for me.