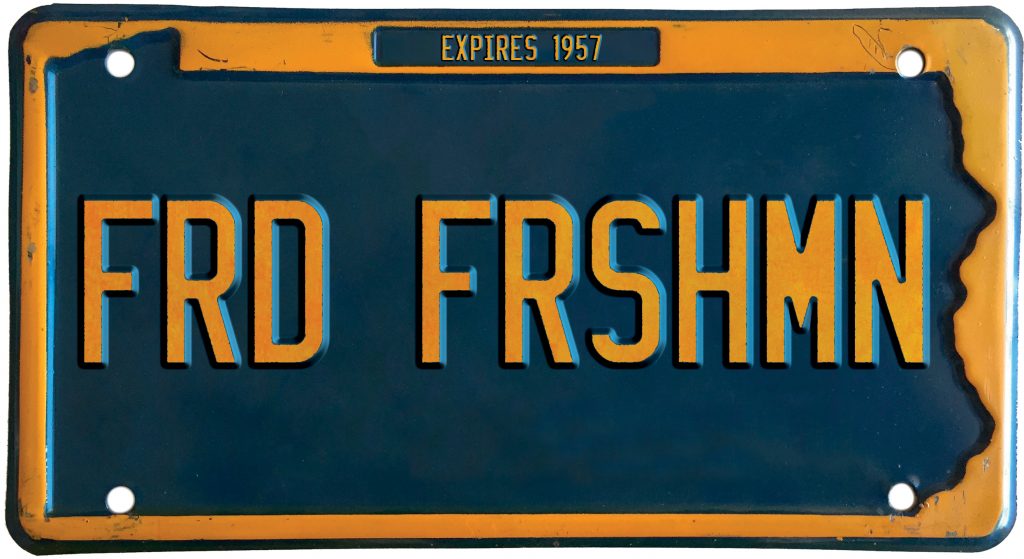

Ford Freshmen

A teenager in upstate New York in the early 1950s, Chuck Hage ’56 was bored with high school. He wasn’t receiving a particularly good education, either. Then his father found out about a new scholarship program that offered the right student an opportunity to step into college two years early and met with a high school counselor to learn more.

It turned out that the Ford Foundation, one of the nation’s largest charitable endowments, was backing a program to send hundreds of young men and women, 16 or younger, to some of the most prestigious colleges and universities in the nation, including Lafayette.

All you needed were good grades, a successful interview with a Ford Foundation representative, a high score on the entrance exam, and a willingness to leave home and family early, when the rest of your friends were enjoying teenage life in high school.

Hage jumped at the opportunity.

In the 1950s, Lafayette was among a handful of colleges and universities selected to participate in an experimental scholarship program that targeted exceptional teenagers to begin their collegiate careers early.

The intent of the pre-induction program, which lasted from 1951-57, was to admit the best and brightest students two years early, before they possibly could be drafted into the military, creating an incentive for them to finish college after discharge from the service. During the Korean War, Congress lowered the draft age to meet demands of the war.

Looking back, Hage says the program taught him to tackle any challenge.

“It taught me that it’s not just brains, it’s work,” he says. “Put your shoulder into the job and just plow through.”

He was not alone when he came to Lafayette as a young teenager. The Class of 1956 had at least a half-dozen pre-induction scholars eager to make their mark and prove to themselves that they could keep pace with older students.

All of them produce detailed, vivid memories of their experience, which exposed them to tough, less-than-coddling faculty who gave them an early jump-start into their professional careers.

Just 15 when he came to Lafayette, Hage, who majored in mechanical engineering, wasn’t sure he would make it through his first year.

“I knew I wasn’t alone because other kids had lousy grades at midterm in their freshman year,” he recalls. “But by the end of the first semester, I was surprised that I survived and some people around me had not.”

For one of Hage’s classmates, Paul Howard, the expectations for him were indisputable.

It was arguably the best foundation I ever had and served me extremely well after I graduated and into my first jobs

“It was made clear to me by my father that this was my opportunity for college,” he recalls. “He had expectations that I would take advantage of this opportunity. There wasn’t a question that I was going to knuckle down.”

Howard was living in Arlington, Va., when his father, who worked as a civilian for the Navy, started searching for college scholarships for his son.

“My parents were worried about me being drafted into the Korean War,” he says. “My father, as an employee of the Navy, knew full well that the war was coming and found out about the pre-induction program.”

“The given reason for the Ford program, as I understood and my father understood, was that the Russians were churning out engineers at an alarming rate and we were not,” Howard says.

The premise of the pre-induction program was, “OK, we can catch up to the Russians. One of the aspects of the Russian system was that they started advanced education a year or two earlier than we did at that time.”

Fellow Class of ’56 Ford Scholar Harold Hartman, who grew up in Port Royal, Pa., north of Harrisburg, heard about the program from one of his high school teachers who received a promotional brochure. “Between him and my dad, we talked about it and started the process,” he says.

Hartman, a chemical engineering graduate, remembers his mother being the most concerned about the early separation, recalling her reaction when he was left at Lafayette for the first time in fall 1952.

With an itch to get a head start on life’s possibilities, he never experienced homesickness. “I was mature enough to participate in the Lafayette adventure and traveled on vacation trips with my uncle in earlier years.”

Hage and Howard fell into college life easily also.

A resident of South College, Hage never felt out of place around older students. “I didn’t have much time for a social life, other than a couple blind dates, but I didn’t expect to have a social life in that first year,” he says. “I was concerned about getting through the academics. By the first semester of my sophomore year I was on the dean’s list, and for three years enjoyed a pleasurable college life.”

His father, who initiated his entry into the program, was supportive of Hage leaving home at an early age.

“My mother was concerned, but she didn’t express it much,” he remembers. “I think a large part of their attitude was based on the fact that my grandparents were all immigrants, including my father, who was 6 years old and wasn’t allowed to continue his education. He was pulled out of school to go to work and always wished he had

a college education.”

After graduating from Lafayette, Hage served in the Army in France. Upon returning, he resumed his studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic, earning a degree in applied math, and worked in the aerospace industry privately and with NASA as his career evolved from research and development to business development and investment management. His granddaughter, Annie Hage ’21, is an economics major and plays lacrosse at Lafayette.

Less socially inclined, Hartman hunkered down with his books in his South College dorm room where he occupied the center bedroom of a three-bedroom suite. Lafayette’s academic rigors, particularly English Composition, Foundations of Engineering, and Engineering Drawing, were difficult. “But the second semester was a bit better,” he recalls.

“During my last year I worked part time at various tasks involved with serving meals at the Watson Hall social dorm, including serving dishes of green-colored mashed potatoes on St. Patrick’s Day and returning them uneaten to the kitchen,” he says.

“The program permitted me to get a two-year earlier start in the working world in July 1956 and use my chemical engineering training in a position at Union Carbide’s nuclear division in Oak Ridge, Tennessee,” Hartman says.

The Ford Foundation selected students who were of average intelligence, “maybe a little smarter,” Howard says, “who by their upbringing had not been homebodies.” Growing up during World War II, he remembers how his family moved frequently because of his father’s work with the Navy.

His parents had some concerns about their son leaving home early, “but those concerns were overridden by the Korean War,” Howard says.

But for the most part, Howard (physics) kept on the straight and narrow and got through Foundations of Engineering, which he says was the hardest course he took at Lafayette.

“It was arguably the best foundation I ever had and served me extremely well after I graduated and into my first jobs,” Howard says. “It was the fuel that made the scientific portion of the pre-induction program work.”

After graduation he went to work for Glenn L. Martin Co., an aircraft and aerospace manufacturer in Baltimore, first as control analyst and later in flight testing to gather data on the accuracy of guidance systems. He later formed his own company and is still active as a consultant for the Navy, designing sensors for diagnostic systems for aircraft and ships.

For the Class of 1956, it was a stellar year to find a job. “Graduates had the pick of jobs, whatever they wanted,” remembers Howard, who chose from five offers as a 19-year-old. “I would have never gone to college and had these opportunities without the pre-induction program,” Howard says. “The fact that it was an accelerated program forced me to work harder, and that experience more than 60 years ago has served me well throughout my life and career.”