Mending the Gap

Jim Petrucci (left) and Berrisford Boothe ’83 are acquiring works for the Petrucci Family

Foundation Collection of African American Art.

Berrisford Boothe ’83 was in New York City previewing his first major art auction when he struck tarnished gold. He couldn’t wait to bid on a portfolio of prints collected by Romare Bearden, one of the most important African American artists of the 20th century. Bearden had come of age and influence during a historic explosion of work by black artists, writers, and singers in a cultural phenomenon that became known as the New Negro Movement.

“It was clear the collection was a web of influence and ability and power of Negro artists condensed into one thing,” says Boothe, a talented and prolific multimedia artist, art professor, and most recently, art curator.

But there was a problem, possibly a really big one. Much of the selection of Bearden’s work, which was being auctioned in a single lot, had been improperly stored and was damaged by moisture and ink-transfer staining.

Boothe went to the auction house bathroom to discreetly place a call to a lifeline and friend, Lewis Tanner Moore, a renowned collector of African American art who would have ideas about both the value and viability of the damaged work. When Boothe walked back out, he was armed with assurances the stained prints could be restored and were more than worth the price of doing so.

Boothe bought the portfolio for a fair price, outbidding rivals he believes were uncharacteristically wary due to the moisture damage. After the stained prints went through a restoration and conservation process, he placed the Bearden portfolio in its new home—the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection.

The collection is a body of nearly 230 works by African American artists, including one by its Jamaican-born curator, that Boothe has taken to noteworthiness in just four years. His partner and patron in this remarkable endeavor is Jim Petrucci, a prominent real estate developer in New Jersey and the Lehigh Valley. Last year, the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection

was sampled at three institutions, including the African American Museum in Philadelphia.

A fourth major exhibit is scheduled to open in early 2017 at the Portland Museum of Art in Oregon.

The Petrucci collection started as most of its brethren do—as an investment. But as Boothe and Petrucci, two longtime friends, began gathering its first works, a personality and purpose of its own began emerging from the collection.

THE RIGHT PERSON

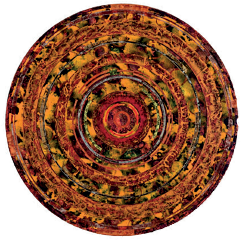

Berrisford Boothe Now Everywhere Surrounding

The collection formed in June 2012. Petrucci was visiting galleries in Montreal with one of his four children when he decided he wanted to start investing in art. When he got home, he called Boothe, a friend he had met years earlier when Petrucci and his wife, Jeanne, went on a 1988 tour of artist studios in Easton and bought two of Boothe’s monoprints. The prints still hang in the couple’s dining room.

“He wanted to know what I thought about collecting art as an investment,” says Boothe, describing the post-Montreal conversation. “I said, ‘It’s a no brainer. You get the right person, you get the right art.’ It never occurred to me that he was asking for my involvement.”

“We want to collect master works that define humanity, that show characters in their full, most authentic human moments.”

– Berrisford Boothe ’83

For Petrucci, formerly a defensive tackle at Princeton University and founder of J.G. Petrucci Co. Inc., the design and construction company that bears his name, any prosperous business is built on getting the right people. And for almost 30 years, he had watched Boothe successfully take on many roles: Abstract painter. Realist printmaker. Abstract/realist photographer.

Collaborator with improvisational musicians. Installation/conceptual artist. Inspirational professor of African American art. An original actor/founder of Lehigh University’s Africana studies program. Incessant visual media experimenter. Regular challenger of the status quo. In other words, the right person. Petrucci made the offer.

Boothe was hesitant. It didn’t seem like the right time. He was still producing work and marketing a national and international career as an artist, never mind deciding whether or not other established artists’ work was the right stuff for a collection. He also loved teaching and didn’t want more meetings and more travel to get in the way of that.

Petrucci was undeterred. He persisted, pointing out the impact and excitement a collection could bring with the right curator. The two talked a while longer. Boothe put together a six-page, five-year business plan. Interestingly, it didn’t involve specifically collecting African American art.

THE RIGHT ART

The first piece Boothe purchased for Petrucci was a pencil wash drawing. Although the French artist, Alix Aymé, was white, the drawing was a compelling, sympathetic study of a young black Moroccan woman. Boothe then picked up The Rehearsal by African American painter Avel deKnight. Next came the purchase of a neo-Cubist piece by Beni E. Kosh, an abstract painter from Cleveland, Ohio, who received little recognition before his death in 1993.

“We kept getting these lovely pieces by African American artists by recommendation or by default,” says Boothe, who received a bachelor’s degree in art at Lafayette College and an MFA in painting from The Maryland Institute College of Art. “At one point Jim says, ‘You know, I’m not really feeling the proposal you wrote. What if we just buy work by African American artists?’ ”

Turns out, Boothe had stumbled into some unfinished business of Petrucci’s. As an American history major at Princeton, Petrucci had interestingly devoted his senior thesis to the white and black patrons who supported African American writers during the Harlem Renaissance.

The first time Boothe had heard about the thesis was in 2014 when collecting for the PFF was well underway. “It was one of those OH-MY-GOD moments,” says Boothe. “I was astounded by the circumstances of fate.”

Petrucci describes the decision to refocus the collection from his viewpoint as a historian. “I don’t think you can really understand American history if you don’t understand African American history,” he says. “If people can’t try to walk in each other’s shoes, we’re going to continue to slide backward.”

As the Nobel- and Pulitzer-winning author Toni Morrison once said, “You can’t see America unless you see it through the eyes of blacks as well as slaves.” The collection not only confronts the legacy of slavery, it celebrates the beauty, compassion, strength, and persistant culture of African Americans.

Young African Americans need to see their race and culture as integral to America more than anyone, adds Boothe. “You have people growing up without a prescriptive, positive sense of their selves,” he says.

“If you’re not represented in the historical context, you don’t see yourself as valuable.”

What began as a straightforward investment now promotes a specific mission: To create a diverse and important collection that strives to bring awareness to the talents and contributions of black artists, whose work is often ignored and historically underrepresented in museums and galleries. It’s also an effort to paint a more accurate and comprehensive picture of America’s history and act as a catalyst for conversation, scholarship, and education.

“It’s a great sense of doing our part to preserve a culture and demonstrate that America simply wouldn’t be America without the influence and contributions of people of color. Instead of an ecumenical mission, it’s a spiritual mission,” says Boothe, who lacking a formal degree in art history, taught the African American seminar Africans in the New World for many years. “So many students had no idea black people made art of this caliber, or suffered, or risked their lives to define themselves and their experiences in America. I’m so grateful that life unfolded in this way, granting me the ability to be a custodian of great treasures of American art.”

In just four years, Boothe and Petrucci have acquired African American art covering such broad subjects as identity, community, history, and common cultural experiences. Calvin Burnett’s ink drawing Man Shortage depicts women dancing together while men are off fighting in World War II. Hale Woodruff’s Coming Home, a cubist/surrealist linoleum cut, represents a return to the American South from 1920s Paris, where many expatriate black artists worked alongside Picasso and other notables of the time. Jacob Lawrence, best known for his vibrant, sharp portraits of black Southern agrarians who migrated to the industrial North, contributes Confrontation at the Bridge, a well-known iconic silkscreen of ’60s racial conflict.

“A lot of collectors are building their collections and preserving the legacy of our culture.”

– Berrisford Boothe ’83

Boothe also has paid close attention to art from African American women, whose work often has been even more marginalized or ignored by museum curators and gallery owners than that of African American men. He has acquired works ranging from Sonya Clark’s Afro Abe, a $5 bill with Abe Lincoln sporting an Afro of ground peacock feathers, to Kara Walker’s silhouette of a black woman shouldering a larger silhouette of a white grand dame. Walker’s work can create quite a stir, such as in 2014 when she displayed a 35-by-75-foot sculpture of a sphinxlike Aunt Jemima figure, made of sugar-coated foam, in an abandoned sugar factory in Brooklyn. Boothe was among the more than 150,000 who visited the installation, conceived as a statement of monumental proportions on overworked, underpaid blacks and black artists.

“What we’re offering here are corrective, positive images that sometimes address long-standing negative perceptions and ignorance,” says Boothe. “We don’t want to just collect pretty pictures that whitewash black life. We want to collect master works that define our humanity, that show characters in their fullest, most authentic moments.”

Young people played an important part during last year’s exhibits of works from the Petrucci collection. Youngsters drew their own versions of images at the African American Museum in Philadelphia. African studies students wrote intimate essays in the Gettysburg College catalog. At William Paterson University a roomful of Irvington High football players heard Debra Priestly, an inventive African American multimedia artist, describe how she preserves her family heritage as ghostly pictures in pickling jars.

“I’d like to get the collection into the hands of as many young people as humanly possible,” says Petrucci, whose family foundation supports ambitious inner-city students. “My interest is to make it very child- and family-friendly. I’d like it to be the kind of collection that will be comfortable for my two children in their 20s as well as my 7- and 9- year-olds.”

Boothe is inspecting recent acquisitions at the collection storage facility in Philadelphia.

THE RIGHT PEOPLE AND THE RIGHT ART

As the friendship between Boothe and Petrucci developed and deepened into a partnership, both men learned to reexamine their understanding of the thing called value.

Petrucci taught Boothe about the business world and the value of tight deadlines and budgets. Boothe taught Petrucci about the art world and how it can reveal, even create, things of deeply personal value. Both men have learned that walking into an auction having done your homework is invaluable.

“Perhaps we’re setting an example for mutual understanding,” says Petrucci. “Berris has really embraced the project, shaped the project, taken ownership of the project. It’s a good example of a collector finding the absolute best talent and then getting out of the way.”

Petrucci isn’t the only one with plans to get out of the way; Boothe is doing the same. After teaching full time and traveling tens of thousands of miles over the last few years to visit auction houses, galleries, museums, studios, and dealers’ homes, he is currently on a two-semester sabbatical from teaching at Lehigh in order to spend more time making art and building an international audience for it.

It’s time. His assistant, Devyn Leonor Briggs, an artist with Jamaican, African American, and Colombian roots, has jumped in to effectively fill much of the breach. And as the Petrucci Family Collection grows, it parallels a relatively new surge in the value of art by African Americans. There has been a decade-long explosion fueled primarily by the competitive passion of longtime private collectors, recent interest of additional key curators, and auction prices that are still comparatively affordable.

“A lot of collectors are building their collections and preserving the legacy of our culture,” says Boothe. “They’re looking for the gems America has forgotten.”

The activities of Petrucci and Boothe also have contributed to the boom, as exemplified by the 2013-14 sales season at Swann Auction Galleries in Manhattan, a relatively new auction house specializing in fine art by African Americans. In consultation over the phone with Boothe, Petrucci bid nearly double the top estimate for Wandering Boy, a 1940 watercolor portrait by Dox Thrash of a powerful, pensive young man in a white hat and a loose white shirt. As he won the bid, Petrucci also set an auction record for a Thrash watercolor.

“There’s something about the gaze of the wandering boy, or man, that tells me he’s wondering what the future will bring,” says Petrucci. “All young people are concerned and anxious about what the future will bring. We’re all staring into a pretty big world; we’re all wanderers and wonderers.”

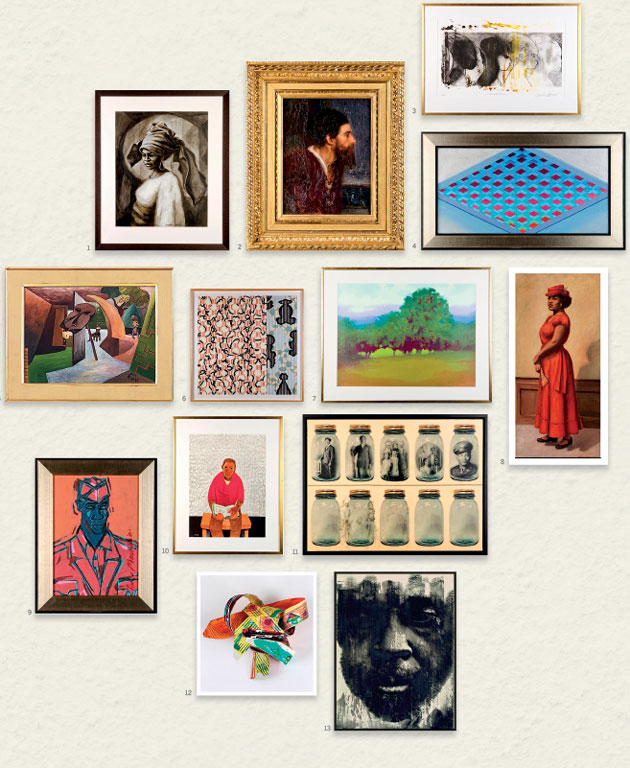

1. Herman “Kofi” Bailey, Young Woman from Yoruba 2. Henry Ossawa Tanner, Nicodemus (Portrait of a Bearded Man) 3. Curlee Raven Holton, Bred for Pleasure 4. James Dupree, Untitled Diamond Form 5. Beni E. Kosh, Mask 6. Charles Burwell, Linear Fragments 7. Richard Mayhew, Atascadero 8. Laura Wheeler Waring, After Sunday Services 9. Deryl Mackie, Pink Soldier

10. Samella Lewis, Untitled-Boy on a Bench 11. Debra Priestly, Mattoon #4 12. Kevin Cole, Dreams Over Memories 13. Donald E. Camp, Man Who Feels Shape