Wired for Success

Jeff Acopian ’75 can’t understand the fuss. What, he asks one dreary day in late March, is so interesting about the 60th anniversary of an unassuming Lehigh Valley company that produces, of all things, power supplies?

“I don’t see it,” he says, shaking his head. It would be easy to suggest that the younger son of the company’s co-founder and namesake is merely being coy. But it’s clear as he sits in an office at Acopian Technical Company’s Easton headquarters discussing family business with older brother Greg ’70, nephew Alex Karapetian ’04, and other nephew Ezra ’03 joining in on the phone from the company’s Florida manufacturing facility, that he’s anything but.

Alex Karapetian ’04 (L-R), Jeff Acopian ’75, Greg Acopian ’70, and Ezra Acopian ’03 at Easton headquarters

Unassuming? Perhaps to a fault given that it’s just not in the Acopian family’s DNA to brag about a Who’s Who client list that includes Walt Disney Company, General Motors, and Boeing. NASA came calling in 1969 for Apollo 11, which delivered the first men on the moon, and again in 1995 with specific power needs for the Hubble Space Telescope. Hollywood film production companies also have sought out Acopian as do the Oscars and Times Square New Year’s Eve ball drop. And perhaps there was no bigger patron than the U.S. government, which in 1971 tapped Acopian for President Nixon’s historic trip to mainland China. Since its founding in 1957, the privately held company has sold millions of power supplies around the world.

After some more discussion and reflection on their milestone, Jeff grudgingly agrees that yes, there is something special about Acopian and the family of Lafayette graduates behind its success. But getting them to talk about it is a different matter.

“That’s not how we were raised,” says Jeff. “Blame my dad.”

Jump Start

Sarkis Acopian ’51 spoke little English when he arrived at Lafayette in 1945. He was born and raised in Iran, the middle child of two dentists who lived in the city of Tabriz, which was home to a large population of fellow Christian Armenians. The family later moved to Tehran, where Sarkis’ goal was to be an engineer. During a chance encounter there, he met two American GIs who told him about a small college in Easton, Pa., with a great engineering program.

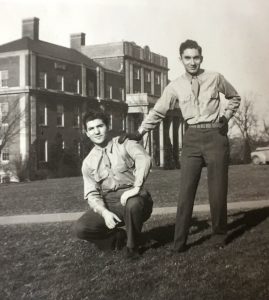

Sarkis Acopian ’51 (right) and friend in front of Markle Hall.

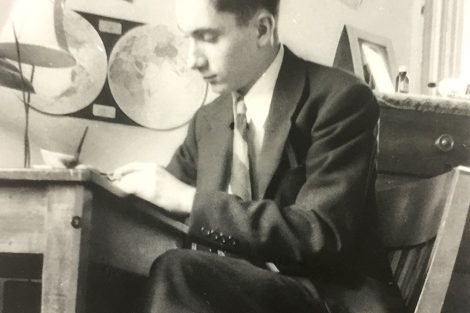

After enrolling in Lafayette, Sarkis was drafted into the U.S. Army and served two tours. It was during the first tour at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas that he met Bobbye Seitze Mixon. She followed him back to Easton, where they married in Colton Chapel, and after graduating in 1951, he put his engineering degree to work at Weller Electric Corp. But his mind would wander, looking for the next big invention.

“He’d always sit on the living room floor tinkering and soldering electronic equipment together,” says Greg, 68. “He was always searching for something.”

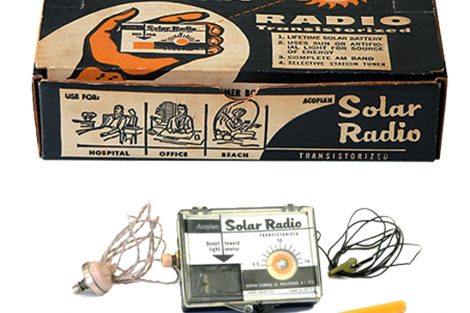

In 1956, Sarkis decided to go on his own and opened a small shop in Phillipsburg, N.J., with partner Thomas A. Workman ’51. They did contract work, with Sarkis in charge of design and manufacturing while Workman handled sales and advertising. It was just a year later when they decided to make their own products and officially named their business Acopian Technical Company. Their first invention, the Acopian Solar Radio, was a small gadget that operated via light and was advertised as having a lifetime battery. The invention was ahead of its time and drew some press and high praise, but few sales.

Undaunted, the small firm moved across the Delaware River in 1958 to Spruce Street in Easton, and soon Sarkis’ attention turned to power supply equipment. “He couldn’t find a power supply for something he was working on and designed one himself,” says Alex. “He realized that if he couldn’t get a power supply quickly enough, then other companies would be having the same problem.”

While business grew slowly, a breakthrough came in 1963. Power supplies, which convert electric energy and protect sensitive electronics from damage during sudden power surges, would, by their nature, take weeks to manufacture and ship. But Sarkis and Workman came up with a novel idea: They shook industry standards by promising to deliver customer orders in three days. It was a promise that not only assured the future growth of the firm, but remains a staple of Acopian’s business today.

Customers, new and old, responded, and a year later the company moved its headquarters to its current address off Loomis Street, tucked between a residential neighborhood and Route 22. As the company grew, Sarkis indulged in several hobbies, all with varying degrees of danger.

On weekends, for example, he’d quietly travel to an airport in Hackettstown, N.J., and board a small plane. When it reached a certain altitude, he’d jump. “My dad used to parachute,” says Jeff, 63, pointing to his father’s faded World War II-style parachute sitting in a corner. “He did over 250 jumps in Hackettstown. He didn’t want to tell people that he did it and kept it a secret.”

When he wasn’t parachuting or scuba diving in deep quarries in New Jersey, Sarkis earned his pilot’s license flying over Blue Mountain, where he’d do tricks, legal and otherwise.

“What can you say?” says Jeff. “He loved adventure and excitement.”

Powering Up

Despite Sarkis’ success as an entrepreneur and local business leader, he never pressured his sons to follow in his footsteps to Lafayette or even to the family business.

They were expected to forge their own paths. Still, it came with little surprise when both Greg and Jeff sought early admission to their father’s alma mater.

Greg arrived at Lafayette in 1966 and a year later took up a hobby that infuriated his father but would become a mainstay through the rest of his life: surfing.

I sent you all over the world, and now you want to be a surf bum.

“I had a roommate who was a surfer, and he showed me how to sneak into an Army base on the Jersey shore,” says Greg, who moved to Florida after graduation and then headed to California. “My dad wasn’t thrilled. He said, ‘I sent you all over the world, and now you want to be a surf bum.’”

After three years he returned home to a job at Acopian, but stayed there less than a year.

“I didn’t like it,” he says. “So I took a job at a radio station.”

Younger brother Jeff arrived at Lafayette in 1971 and quickly made his mark along with friend Dave Farer ’75. Both guitar players, they formed a two-man group called It’s Not a Hoagie and performed a mix of Grateful Dead; Crosby, Stills, & Nash; and originals around campus, starting with wine and cheese get-togethers and then frat parties, earning up to $250 per performance.

Much to his father’s dismay, Jeff also took up surfing—thanks to his brother—and, after graduating with a degree in electrical engineering, accepted a job building satellite antennas in Nigeria. He was back in the states less than a year later working for a computer company in San Francisco, but wanderlust got the best of him, and he moved to Japan where he worked, studied martial arts, and traveled throughout Southeast Asia.

“My mom thought I’d never come back,” he says. “But after living in Japan, working with my father seemed like a stupid thing not to do. It was a good company, and it seemed like a waste not to work there.”

Jeff returned to Easton in 1980, with Greg eventually following him to the firm but to the Melbourne, Fla., facility, which was close to the beach. Sarkis would fly the company-owned Cessna Citation back and forth between his Easton headquarters and Florida. Greg remained there until 1986, when Sarkis called him home. It was time for his boys to be groomed to take charge of the company.

By the late 1990s, Sarkis had turned over day-to-day control to Greg and Jeff. But the transition came at a time when the world was changing how it did business, and U.S. manufacturing companies began to feel the effects of foreign competition, particularly from China.

Fully Charged

According to the Economic Policy Institute, a London think tank, China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001 has cost 3.2 million American jobs, including 2.4 million in manufacturing. Unable to meet the widening price difference offered by cheaper labor and materials overseas, many U.S. companies were forced into layoffs or out of business altogether. Today, China accounts for two-thirds of the $32 billion global power supply business.

Acopian Technical Company did not go unscathed. Business suffered, and for the first time in its history there were a few layoffs. But after several lean years, the next generation of Acopian family Lafayette graduates had arrived, and with them came new ideas.

Greg’s son Ezra, now 36, and Alex, 35, never envisioned themselves working for the family business after graduating from Lafayette, but providence has a funny way of rerouting intended directions.

Ezra’s journey to the family firm began in 2004 with a simple wish to move from his job in central Pennsylvania to Melbourne, where he was born and where his mother’s side of the family resides. With no plans other than hanging by the beach and tinkering with the idea of joining the Marines, Ezra received a call from his father.

“My dad said he had a warehouse stocking position to fill in Melbourne and do I want the job,” recalls Ezra. “I had to fill out an application and give references.”

Ezra got the job and was later elevated from the warehouse to manager of purchasing and facilities. Alex arrived at Acopian in 2006—one of his references was family friend and Lafayette’s 15th president Arthur J. Rothkopf ’55.

You can say they are the future of Acopian.

An outgoing personality in a family of introverts, Alex focused on the company website, online advertising, and social media, and began heavily promoting the company’s ability to create American-made, custom systems to meet the exact needs of a client and its three-day delivery promise.

Greg credits Ezra and Alex with bringing fresh ideas to the company and helping it grow by attracting new clients, including ones in the alternative energy industry.

“You can say they are the future of Acopian.”

Surging Forward

With the future now set in Ezra and Alex, Acopian’s founder was nearing his end.

It had been more than 10 years since Sarkis Acopian stepped back from the day-to-day control of his company to focus on his philanthropy, which extended throughout the Lehigh Valley and beyond. He had for years given money to a host of charities, causes, and projects under condition that he not be recognized, including the $1 million he contributed for the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. “He was the largest single donor,” says Alex. “He sent the check regular mail.”

But age, a sense of his mortality, and a desire for a legacy moved him to add his name to some of those gifts. There’s the Acopian Ballroom at the State Theatre in Easton, the Acopian Center for Conservation Learning at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Kempton, Pa., and the Acopian Center for Ornithology at Muhlenberg College. And never forgetting his roots, he had over the years contributed to a variety of Armenian organizations and causes, including three churches and American University of Armenia and the Acopian Center for the Environment, both in Armenia.

In 2002, he decided he wanted to do something for Lafayette. A year earlier he had been approached by Gary Evans ’57, then vice president for development and college relations, who sought out alumni to discuss financial support. Evans recalls meeting with Sarkis at Marblehead Chowder House on William Penn Highway in Easton, where Sarkis had a standard table.

“They called it the Acopian table,” says Evans. “We were in a capital campaign, and I asked him if he’d be interested in making a significant gift, and he said no.”

Despite this refusal, the two men would meet at the same restaurant and table for lunch every two months or so. It was a year after Evans’ first approach when Sarkis announced that he did have something in mind.

“He said he wanted to do something substantial for the school,” says Evans.

At the dedication for the the 90,000-square-foot Acopian Engineering Center in 2003.

That substantial contribution from Sarkis and Bobbye Acopian resulted in construction of the 90,000-square-foot Acopian Engineering Center on campus. At the dedication for the new building in 2003, Evans says Sarkis didn’t speak, preferring instead to have sons Greg and Jeff do the talking.

“He was very shy and modest,” says Evans. “He was successful but wasn’t one of those people who’d wave it in your face. I’m proud to have called him a friend.”

Sarkis died on Jan. 18, 2007, following a lengthy illness, and a decade later the Acopian family continues to maintain its strong ties with Lafayette.

In 2009, the company began offering winter and summer internships to Lafayette students. One former intern, Bill Hoffman ’10, now works there as an engineer. Alex served as president of the Lafayette Alumni Association from 2014 to 2016, and currently serves on the Board of Trustees’ Grounds and Buildings Committee. Acopian was also a sponsor last year for the 150th anniversary celebration of Lafayette engineering. And yet another Acopian, Jeff’s daughter Natalie ’19, is majoring in film and media studies.

Meanwhile, Acopian Technical Company continues to add to its stellar client list. The NFL tapped Acopian for the 2014 Super Bowl at MetLife Stadium in New Jersey. IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the South Pole turned to Acopian for Project Ice Cube, a particle detector. And Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Tesla reached out from their respective headquarters in California for custom-made Acopian power products.

The company’s 60-year story continues to evolve. “We had to reinvent ourselves,” says Greg. “But our core values never changed. We’re engineers. It’s in our genes.”