In the Marquis’ Footsteps

The Marquis de Lafayette was 19 when he first came to America in 1777 to fight for his freedom. When he returned in 1824 for his farewell tour, the Frenchman was 67. By then, the entire nation celebrated his name as he made his way through all 24 states in the Union.

In this issue, we follow the Marquis to Savannah, Ga., where he arrived March 19, 1825, by steamboat and was greeted on the shore “by the entire population and militia assembled together, who had been waiting for several hours,” according to the journal of Auguste Levasseur, Lafayette’s private secretary, who accompanied him on his 14-month trip as a Guest of the Nation. “Soon we heard the majestic welcome of the artillery and the shouts of the people. We responded to them by the cannon-fire from our ship and by the patriotic tunes that our band caused to echo from the shore.”

In this issue, we follow the Marquis to Savannah, Ga., where he arrived March 19, 1825, by steamboat and was greeted on the shore “by the entire population and militia assembled together, who had been waiting for several hours,” according to the journal of Auguste Levasseur, Lafayette’s private secretary, who accompanied him on his 14-month trip as a Guest of the Nation. “Soon we heard the majestic welcome of the artillery and the shouts of the people. We responded to them by the cannon-fire from our ship and by the patriotic tunes that our band caused to echo from the shore.”

Before arriving in Savannah, Lafayette and his entourage stopped at Edisto Island, where William Seabrook, a wealthy planter, hosted a dinner and ball for the Marquis, then asked him to baptize his infant daughter, whom he named Caroline Lafayette.

Trace Lafayette’s journey through Savannah’s tidy squares, elegant mansions, and towering oak trees.

Savannah GUIDE

1. Owens-Thomas House

124 Abercorn St.

telfair.org/visit/owens-thomas

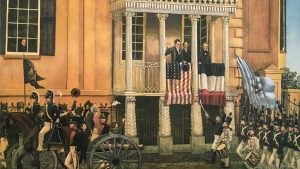

Lafayette stayed at the Owens-Thomas House in 1825 and from its south balcony gave a speech to a group of townspeople. Construction of the mansion was completed in 1819 in posh Oglethorpe Square, and it was one of the first homes of the century to have indoor plumbing and a flush toilet. Now a museum, the historic house features one of the oldest urban slave quarters still intact, and a spine-tingling reputation for being haunted.

Lafayette stayed at the Owens-Thomas House in 1825 and from its south balcony gave a speech to a group of townspeople. Construction of the mansion was completed in 1819 in posh Oglethorpe Square, and it was one of the first homes of the century to have indoor plumbing and a flush toilet. Now a museum, the historic house features one of the oldest urban slave quarters still intact, and a spine-tingling reputation for being haunted.

2. Chippewa Square

1-11 E. Perry St.

savannah.com/chippewa-square

You may recognize Chippewa Square from the bench scene in the 1994 film Forrest Gump, but that was long after Lafayette laid a cornerstone there in 1825 for a statue to Revolutionary War hero Gen. Casimir Pulaski, who died of wounds received in the Siege of Savannah. Citizens weren’t able to raise enough money to complete the project, and in 1853 it was moved to Monterey Square where a 55-foot marble obelisk was erected. Pulaski is alleged to be buried next to the monument, but a medical examination of the body a few years ago was inconclusive. Monterey Square is also the site of Mercer House, residence of the late restorationist and antiques dealer Jim Williams, who was featured in the 1994 novel and 1997 film Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.

You may recognize Chippewa Square from the bench scene in the 1994 film Forrest Gump, but that was long after Lafayette laid a cornerstone there in 1825 for a statue to Revolutionary War hero Gen. Casimir Pulaski, who died of wounds received in the Siege of Savannah. Citizens weren’t able to raise enough money to complete the project, and in 1853 it was moved to Monterey Square where a 55-foot marble obelisk was erected. Pulaski is alleged to be buried next to the monument, but a medical examination of the body a few years ago was inconclusive. Monterey Square is also the site of Mercer House, residence of the late restorationist and antiques dealer Jim Williams, who was featured in the 1994 novel and 1997 film Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.

3. River House Savannah

125 W. River St.

savannahriverhouse.com

Lafayette never wet his whistle at the River House (it wasn’t a restaurant then), but he would have appreciated a swig of its Chatham Artillery Punch, concocted in colonial times by Georgia’s oldest military organization. Organized in 1786, the group’s first duty was to pay tribute at the funeral of Revolutionary War hero Gen. Nathanael Greene. The artillery also thundered its welcome to Lafayette when he arrived in Savannah. The punch, which includes a mixture of champagne, rum, brandy, and bourbon, used to be served in horse buckets during celebrations. Today it comes in a snifter, but its potency hasn’t dimmed.

Lafayette never wet his whistle at the River House (it wasn’t a restaurant then), but he would have appreciated a swig of its Chatham Artillery Punch, concocted in colonial times by Georgia’s oldest military organization. Organized in 1786, the group’s first duty was to pay tribute at the funeral of Revolutionary War hero Gen. Nathanael Greene. The artillery also thundered its welcome to Lafayette when he arrived in Savannah. The punch, which includes a mixture of champagne, rum, brandy, and bourbon, used to be served in horse buckets during celebrations. Today it comes in a snifter, but its potency hasn’t dimmed.

4. Johnson Square

7 E. Congress St.

savannah.com/johnson-square

Of Savannah’s 24 squares, Johnson is the oldest and largest, and served for decades as the central hub for social activities. Here the head chief of the Creek Nation recited the origin myth of the Creeks, a reading of the Declaration of Independence took place in 1776, and a ball was held for President James Monroe in 1819. It’s also where Lafayette laid the foundation for a 50-foot monument honoring Greene, whose remains are interred at the site. Today, Johnson Square is surrounded by some of downtown Savannah’s most elegant buildings, including Christ Episcopal Church and City Hall.

Of Savannah’s 24 squares, Johnson is the oldest and largest, and served for decades as the central hub for social activities. Here the head chief of the Creek Nation recited the origin myth of the Creeks, a reading of the Declaration of Independence took place in 1776, and a ball was held for President James Monroe in 1819. It’s also where Lafayette laid the foundation for a 50-foot monument honoring Greene, whose remains are interred at the site. Today, Johnson Square is surrounded by some of downtown Savannah’s most elegant buildings, including Christ Episcopal Church and City Hall.

5. Lafayette Square

199 E. Harris St.

savannah.com/lafayette-square

Lafayette Square was laid out in 1873 in honor of you-know-who and is home to the ornate Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, which boasts the highest twin steeples in the downtown. Also on the square is Hamilton-Turner House, built in 1873 for a wealthy businessman. The first residence in Savannah with electricity, the elegant villa has since been turned into a bed and breakfast. On one corner sits Andrew Low House, whose most famous occupant was Andrew’s daughter-in-law, Juliette Gordon Low, founder of the Girl Scouts. The home is now open to the public as a museum and features works by some of America’s finest furniture makers.

Lafayette Square was laid out in 1873 in honor of you-know-who and is home to the ornate Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, which boasts the highest twin steeples in the downtown. Also on the square is Hamilton-Turner House, built in 1873 for a wealthy businessman. The first residence in Savannah with electricity, the elegant villa has since been turned into a bed and breakfast. On one corner sits Andrew Low House, whose most famous occupant was Andrew’s daughter-in-law, Juliette Gordon Low, founder of the Girl Scouts. The home is now open to the public as a museum and features works by some of America’s finest furniture makers.