Beautiful and Powerful

Chawne Kimber has something to say—and she uses a needle and thread to express it.

If you have the impression that quilts are just cozy bed coverings and quilting trade shows are only frequented by conservative crowds, Kimber’s work might give you whiplash. She uses quilts as a medium through which she provides commentary about topics such as censorship, rape culture, social injustice, and racism.

Kimber’s ability to blend beautiful artistry with powerful, thought-provoking messaging has attracted attention and earned her notoriety in the quilting world. Her work is regularly featured at quilt shows and art museum exhibitions throughout the country. She had 12 quilts on display at Paul Mellon Arts Center in Connecticut through the end of February, and one of her pieces, “The One for Eric G,” was part of an exhibition at Northern Illinois University.

Using cotton as a canvas adds to the evocative nature of her work.

“I have a very deep ancestral connection to the growing of cotton,” Kimber says. “It wasn’t willingly or fun. As a result, cotton has been central in the lives of the women in my family. I remember my great-grandmother’s quilts on my bed as a kid. I liked the idea of connecting to the past and recapturing that memory. But also, there is the underlying message: You can’t talk about race in this country without talking about cotton.”

First Stitches

Kimber started quilting in 2005 shortly after applying for tenure in the math department. After she submitted all her materials and realized it was now out of her hands, the nerves kicked in. Armed with a $50 sewing machine from Amazon and a copy of Quilting for Dummies, Kimber found an outlet for her nervous energy. A year later, she had tenure—and 10 quilts.

The hobby had served its purpose, so Kimber set it aside. But when her father passed away in 2007, she found herself reaching for her sewing machine again. She inherited his vast necktie collection (400!) and decided to stitch them together into quilts she then gifted to her sister and brother.

Once again, the work brought her solace. But something shifted: The quilt wasn’t just an attractive compilation of fabrics. It had a greater meaning, a deeper significance. And that changed her perspective and how she thought about her craft.

“I realized it wasn’t enough for me to just chop up fabrics and put them back together,” she says. “I decided that my work needed to have meaning. And that opened up something new in me and sparked a whole new direction for my work.”

That realization motivated Kimber to learn an advanced technique her great-grandmother had used, called improvisation. “Traditional quilts are made with rigid geometry,” she says. “Improvisation is more like jazz. You get to play. You work with scissors, and you get to use a more organic styling and aren’t limited by the standard angles. For me, it’s an escape from the math.”

This technique enabled Kimber to develop a needlework handwriting. That, in turn, allowed her to express her voice, starting with a colorful endorsement of the First Amendment.

Inspired by comedian George Carlin’s “seven words you can never say on television,” Kimber sewed those seven words on a bright, vibrant, multihued quilt. She put it on her blog in 2008 to test the waters.

“Some people were really excited—and some people were not,” she says. “I got some negative comments, and some people made it personal. But a lot of other people thought it was really revolutionary—to see this on a quilt. I’m not out to shock people. I think it’s good to start conversations, and I like if I can reach a wider audience of people who are willing to have open minds and generate a conversation.”

Kimber has developed a loyal and supportive fan base online. But she relishes in the opportunity to participate in quilt shows and art exhibitions where she feels her quilts can make a stronger statement. Each one is between 5 and 6 feet square, and they have more oomph in person, compared to a two-dimensional photo on a computer screen.

“It’s a completely different experience in person,” she says. “Quilting involves having three layers—a backing layer, an insulating layer, and a decorative layer. It’s very much three-dimensional and is like a sculpture. Flowing woven textiles also have a warmth to them. You are drawn in by the feeling of warmth and comfort that they evoke, and then are surprised by the messaging.”

Kimber shares the inspiration, backstory, and details of three of her creations.

“The One for T,” 2013

The inspiration: “In the aftermath of the killing of Trayvon Martin, a comment was made on social media that if Trayvon hadn’t been wearing a hoodie then the shooting wouldn’t have happened,” Kimber says. “It produced this ‘I am Spartacus’ response. People took photos of themselves in hoodies and posted on social media ‘I am Trayvon.’ I don’t want my social commentary to be so closely tied to an event that you have to know the full details of what happened to be able to interact with the work. And so I decided to explore the idea in an abstract way, by exploring the idea of the politics of fashion.”

The backstory: “This is one of the first quilts I ever exhibited,” Kimber says. “It was at Babson College in Boston. It was at an art venue, which was very important for my development as an artist. I flew there to be at the opening because I wanted that experience. I knew it was important, but I didn’t realize how important. I walked in, and I was an artist. There is a sense in mathematics that I’m still trying to prove myself. But by virtue of making something, I was an artist. It was a true sense of acceptance. I’ve never experienced that in a professional environment so quickly. I also learned a ton. I was surrounded by sculptors and painters and was a sponge. It was wonderful to get to talk to other people about their work. Something in me knew that this was a step into a new life of some kind. It was very exciting.”

The details: “I took self-portraits in a hoodie,” Kimber says. “I wanted to represent the different ways you could be viewed wearing the same garment. I used a pretty high-intensity flash to take two-tone photos of myself. I moved the light source to create different imagery. In one, I look very fierce. In another I look like a nun in a habit. I printed out the images using a large-scale printer on paper. The technique I used is raw-edge appliqué. It was a yearlong project that required a lot of study and a lot of skill development. With appliqué, you stack fabrics and then cut out layers to expose what is underneath. I wanted the fabric I was cutting to be detailed and have a raw edge, which requires a process. You don’t tuck under and sew all the frays. You launder the quilt multiple times so the edges get tangly. It’s an organic, textured look. It’s not tidy, which seems appropriate for an expression of a dirty experience.”

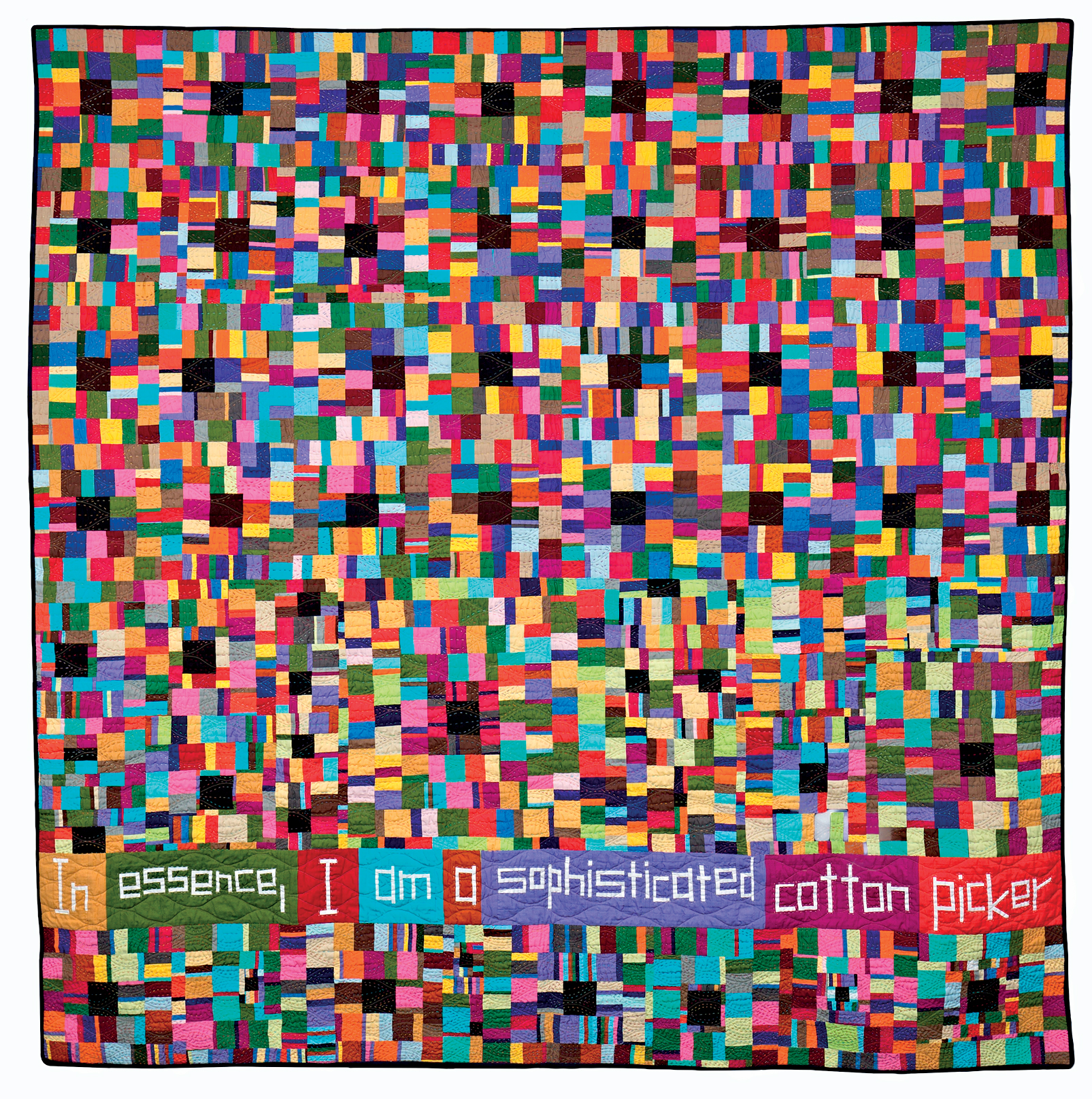

“Cotton Sophisticate,” 2015

The inspiration: “This quote, ‘In essence I am a sophisticated cotton picker,’ comes from Eartha Kitt’s autobiography,” Kimber says. “Eartha Kitt was a very talented singer and actress who broke a lot of barriers. She was born on a cotton plantation and grew up in southern Georgia, not far from where I grew up in northern Florida. The quote is a summation of her life, and it resonated with me. This improvisational patchwork and kantha-style handquilting is a direct callback to the utility quilts my great-grandmother made on a former cotton plantation.”

The backstory: “I made the words first to establish the width of the quilt,” Kimber says. “I wanted them to be legible from a distance. I tried different layouts for the words but having them anchor the design worked best. This is currently on display at a show in Connecticut. It’s been all over the country. It’s a fairly popular piece. I think it’s my best work to date.”

The details: “It’s made of fabrics whose cotton is processed in the United States, which is super. I’m concerned about the labor behind the fabrics that I use, and ones that are made off continent can be questionable. This company, American Made Brand, has 72 different colors, and I used every one of them in this quilt. It looks very random, but it was a very planned quilting pattern. It’s not that I used math—I rarely use math when making quilts. It’s more about knowing color theory.”

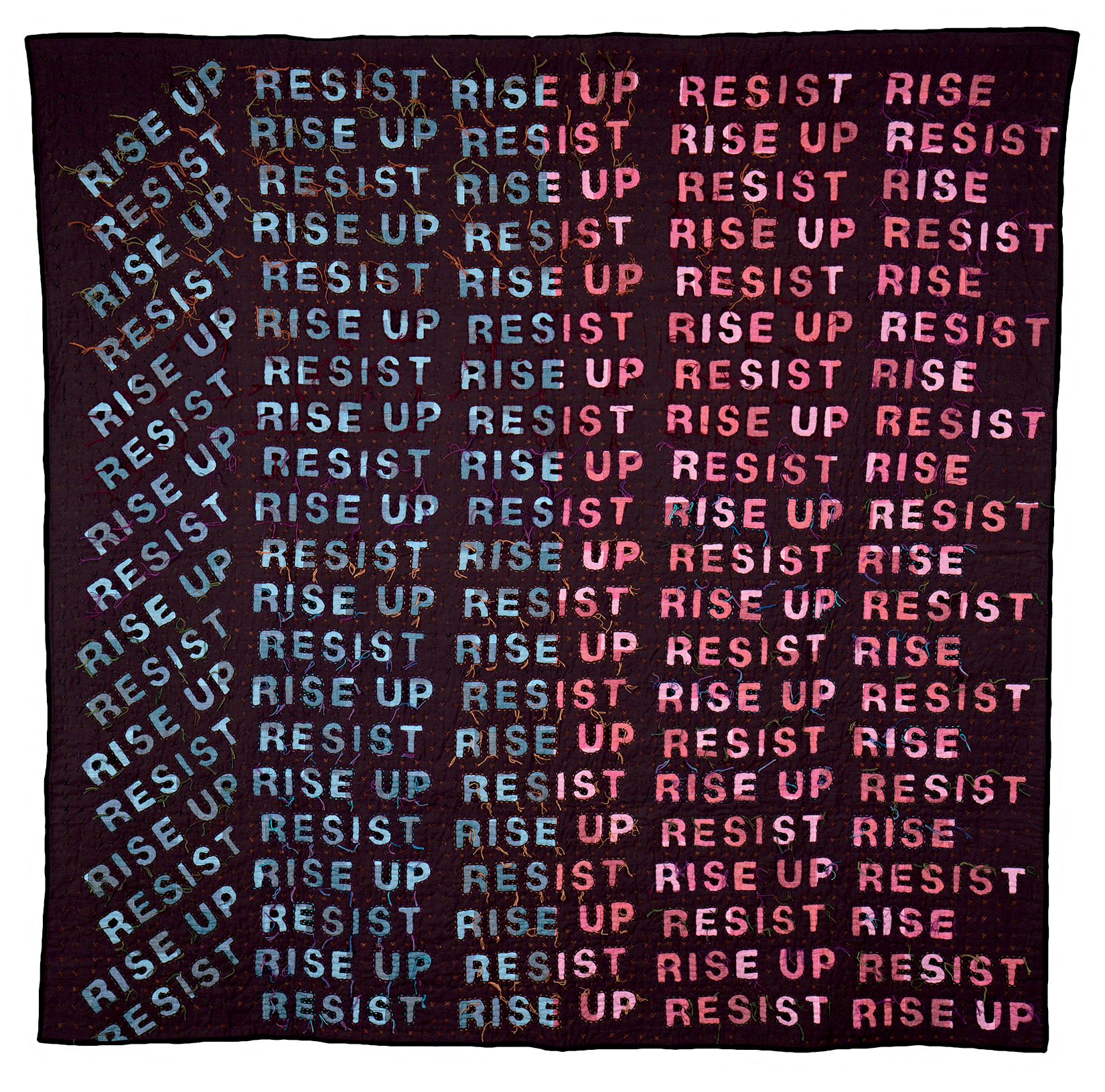

“Get Woke,” 2017

The inspiration: “I started making this on Inauguration Day in 2017,” Kimber says. “I was definitely motivated by the protests and the resistance that have mobilized since Election Day. I decided I wanted to make something to represent that movement. I see this as my form of a protest poster.”

The backstory: “I travel a lot, and this quilt traveled with me,” Kimber says. “I would put this folded up into its own carry-on bag. I would take it out in coffee shops and airports and work on it. People would stop and ask questions or share with me that their mom or grandmother used to sew. It was a way to connect with people. At first, people couldn’t read what it said, but as I made more progress, it became more obvious. I knew that it would generate different reactions, and I was open-minded and ready for whatever came at me. I think we dwell in different information universes, and I think that it’s important that we still try to connect with each other. I may not have changed anyone’s mind. But to have those opportunities to talk and connect with people was just lovely.”

The details: “I used reverse appliqué, in which you cut out the top layer to reveal something underneath—in this case, these words,” Kimber says. “It’s not perfect. You can identify the moments when I was talking to someone and my scissor work got a little sloppy. The under layer is red, white, and blue for symbolism. It flows from red to blue to show that there are people from both sides of the aisle who have concerns, who are resisting. The red and blue could also represent blood and breath.”