Silver Linings

For the final few months of the spring semester, Lafayette faculty ventured into uncharted territory when they were asked to rapidly transition to remote instruction of their courses in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

From facing challenges converting their course materials to Google and Zoom with very little notice, to trying to remain “hands on” with those subjects that require it, faculty members—like students—faced a learning curve when switching to the virtual realm.

True to form, however, they rose to the occasion and embraced the change in order to continue presenting the highest-quality learning experience. They even found ways to continue injecting their own personalities—and drawing out the personalities of their students—in the process.

Creating a virtual geology field trip

When associate professor of geology David Sunderlin realized that his intro course, GEOL 130, would miss out on the spring component of going out into the field, he employed the help of his own children to take his class on a virtual field trip.

“My kids and I hopped into the car, and we drove around to all of these different locations where I would have taken the students. I took pictures, and the kids took videos of me describing the kinds of rocks that there were there, trying to make a virtual field trip as if the students would have gone there themselves,” says Sunderlin. “I posted those videos on Moodle and got myself up to date with how iMovie works, so I even gained quite a bit of video editing knowledge.”

With 44 students in the course, the idea was to expose them to a storybook of Earth’s history—to the outcrops, field exposures, landscapes, and life-forms that live there. Though they didn’t all get to pile into a bus to walk these sites together, experiencing them via video was also a way to connect to the person leading their group.

“I think they saw the humanity in me as their instructor rather than just a talking head,” says Sunderlin. “I tried to keep them attached to the community feeling that we had through the first half of the semester.”

Biodiversity Challenge

Associate professor of biology Megan Rothenberger would have had nine field trips associated with her (conservation) BIO 272 lab—and getting outside and observing nature is a big part of what the course is based on. Without the ability to conduct fieldwork this past spring, Rothenberger got creative and decided to challenge her students in a unique way.

For six weeks, the “Biodiversity Challenge” asked students to get outside, find a species or landscape, learn something about it, and then post what they learned on the course’s Moodle discussion board. From showcasing rocks and flowers in their yards to sharing their community’s nightly expressions of appreciation for health care workers, students shared content that connected them on a personal level and shared all the emotions that quarantine was making them feel at the time.

“The outcome of this assignment was far better than I had hoped,” shares Rothenberger. “Not only were the students enthusiastically reporting on biodiversity in the vicinity of their homes, but they also had such diverse experience to report because they are from all over the place. Reading students’ posts became the highlight of my week.”

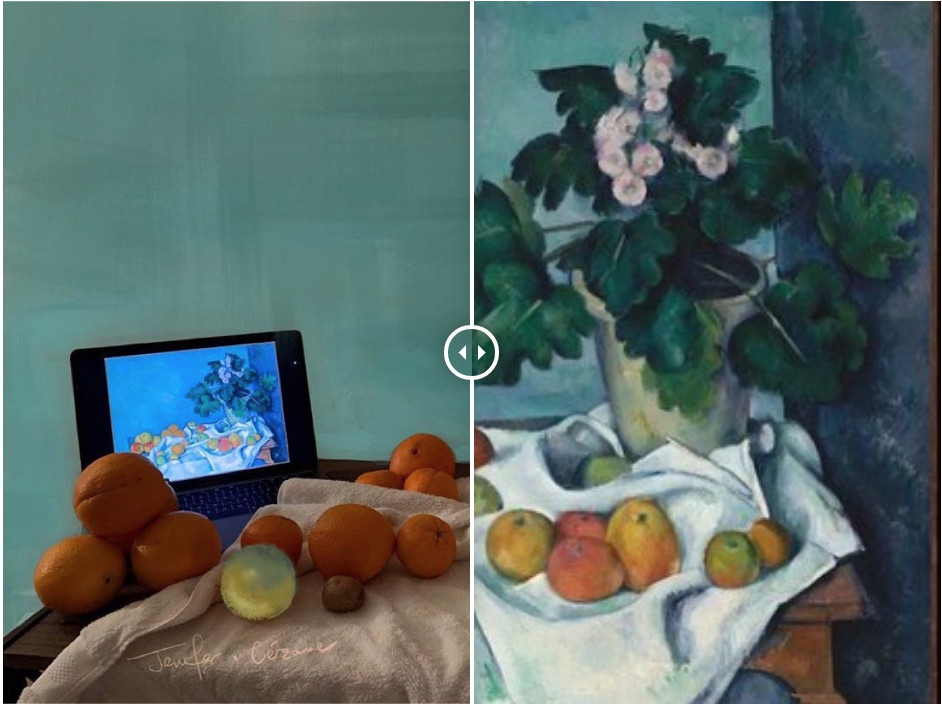

Household items mirror famous works of art

When assistant professor of art Eric Hupe took notice of a social media trend that asked art fans around the world to share photos of themselves bringing their favorite works to life, it inspired him to ask his students to connect with their coursework on a new level.

Ordinarily, Hupe’s ART 102 class spent time writing their responses to artwork they were asked to investigate each week. Once classes went virtual, they were asked to use items they had on hand in their homes to recreate any work of art from the specific time period they were studying. The idea was that the physical act of recreation would require students to intentionally slow down the process they used to analyze each piece—the exact opposite of the few seconds of attention most social media posts receive.

“You have to think about how it’s composed and what elements work, especially when you’re making their recreation out of objects you have on hand,” says Hupe. “Maybe an item in the background of a painting is essential, and you have to find the equivalent, or there are other features in the painting that aren’t essential to its meaning and its power, and you can leave those aside. It reveals more of the artistic invention that goes behind a work’s creation.”

Making beautiful music from a distance

Not unlike countless other music educators around the world who were faced with figuring out how to still have meaningful engagement with their students that was musically collaborative, associate professor of music and director of art Jennifer Kelly did what socially distant choirs, orchestras, and vocalists around the world were already doing—she turned to technology.

Using a free cross-platform app that allowed them to sing and work together, Kelly’s students met every week in small group sections and as a full ensemble. And while this was not a “virtual choir” made up of individual performances, collaborating virtually enabled students to work on their listening and response skills—what Kelly describes as “somewhere between the experience of a live concert and a solo recording.” The groups used drafting, review, and revision steps for each piece.

““We finished our final class and played our ‘concert’ via Zoom,” says Kelly. “It was a meaningful performance for the students, and I am tremendously proud of all of them.”

Responding in new ways

While discussion boards have been a staple of online courses for decades, the ways in which the discussion boards are utilized may not always be the best method of fostering student engagement. Assistant professor of French Annie De Saussure recognized that emphasizing the quality and thoughtfulness of responses over the quantity and frequency of posts would construct the experience around collaboration and foster a deeper understanding of the material.

A presentation from class.

“I used the Moodle forum discussions as ‘homework,’ asking students to answer specific questions in the forum and to comment on each other’s answers. This helped extend conversation beyond the Zoom session, and I found that students came up with really good ideas and responded to each other in interesting ways,” says De Saussure. “Usually I would have students submit homework directly to me. The forum participation as homework is more dynamic, I think, while still engaging students on the material.”

She also noticed that in the Zoom format, some students who were unlikely to participate in a traditional classroom setting were answering or asking questions using the chat function.

“Something about removing the physical layout of the traditional classroom (where I stand at the front of the class and students sit in chairs) makes the Zoom class feel a bit more egalitarian and dynamic,” she says.