Helping Refugees Transition from Surviving to Thriving

The call came after we’d had just a few months of loose training—there’s a family on their way to the area, and they’ll be here in seven days. Do we want to take this family on, and are we prepared to help them?”

Erik Laucks ’20 pauses before recalling what it was like the first time he was able to impact the lives of refugees in 2017.

“There were so many things we didn’t know, and so many things we had to figure out along the way. When we met the family at the airport, none of them could say anything other than ‘hi’ and a couple of basic words. We didn’t even have a plan for what we were doing with them the next day in terms of ‘the process’ of resettlement,” he recalls matter-of-factly. “The initial joy from that first day turns into a feeling of real fulfillment as you can start having conversations with them, you help find them permanent housing, and you figure out how to move them. There’s a lot of ways that refugee families grow and change as a result of our help, but there’s also a lot of ways that we grow and change as a result of helping them.”

When we met the family at the airport, none of them could say anything other than ‘hi’ and a couple of basic words.

At the height of the government-imposed Muslim travel ban, Laucks was part of a core group of students (along with Anna Nollan ’20, Rebecca Webster ’19, Natalie Nollan ’17, Hagar Kenawy ’17, and Rebecca Wei ’18) who sprang into action and submitted a proposal to former President Alison Byerly, asking the College to provide space to host refugee families making a new start in the Lehigh Valley. The group of students had just invited Diya Abdo, the founder of Every Campus a Refuge at Guilford College, to speak at Lafayette.

This was the beginning of Refugee Action (RefAct), a student-led organization that focuses on sponsorship, outreach, and fundraising for resources these new residents need. The club members—who share a passion for service, human rights, and peer education—spend countless hours volunteering their time and energy, and work with Bethany Christian Services of Allentown (Northampton and Lehigh counties’ designated resettlement agency under the umbrella of Lutheran Immigration Services, one of nine overarching organizations across the country that oversees resettlement offices) for incoming refugee referrals.

“We developed a very comprehensive program that was built not only around financial self-sufficiency in the U.S. Self-sufficiency is not enough for people who are coming from traumatic experiences and the sort of experiences that they had to get through to get here,” says Ayat Husseini ’20, who previously served as RefAct’s president of resettlement. “We really structured our organization, our program, and our process not only around self-sufficiency, but also around fulfillment and helping families reach their own personal goals. There’s a level of happiness and joy that we are all entitled to pursue, and we wanted to be able to help them with that.”

What does it mean to be a refugee?

According to the United Nations, of the 79.5 million people forcibly displaced from their homelands by war, persecution, or natural disaster, more than 26 million are refugees who have crossed international borders while fleeing. Unable to return, they depend on federal organizations to help them safely make their way to the U.S. and ultimately restart their lives here.

This is the fundamental difference between refugees and immigrants; according to rescue.org, an immigrant is someone who makes a conscious decision to leave his or her home and move to a foreign country with the intention of settling there. Immigrants often go through a lengthy vetting process to immigrate to a new country. Many become lawful permanent residents and eventually citizens. They are able to research their destinations prior to arrival, including employment and schooling opportunities. Most importantly, they are free to return home if they choose.

Refugees, however, are unable to return home unless or until conditions in their native lands are safe for them again.

How would we feel if we had to leave Pennsylvania and move to Afghanistan, learn the language, put kids in school, and find a job?

“I think it’s important to note that, in general, most refugees don’t want to leave where they’re from. The fact of the matter is most families have had something happen in their country that caused them to flee,” points out Chaplain Alex Hendrickson, director of religious and spiritual life and adviser for RefAct. “How would we feel if we had to leave Pennsylvania and move to Afghanistan, learn the language, put kids in school, and find a job? There’s a level of empathy where you have to try to imagine yourself in this situation.”

“The process of being resettled—while that process can inspire both hope and feelings of relief for families—can also be traumatic in its own way,” echoes Rachel Helwig, development and communications coordinator for Church World Service, a resettlement agency with offices in Lancaster. “Feeling the loss

of a homeland is a pretty stark moment, and the loss of that place they probably continue to love even though it’s not a safe place for them to live.”

Who comes to this country, and more specifically to Pennsylvania and the Lehigh Valley, depends largely on what’s happening in the world and what places are in crisis.

State Department statistics show that just over 440 refugees were resettled in Pennsylvania in (fiscal year) 2020, with most coming from the Democratic Republic of Congo and Ukraine. In the decade before that, many refugees in the state came from Afghanistan, Bhutan, Burma, Eritrea, Iraq, and Syria.

Kibrom Tesfu, refugee employment specialist at Bethany Christian Services who serves as the direct connection between RefAct and incoming refugee families, was one of those who came from Eritrea and resettled here in 2011. Tesfu lived in a refugee camp for six years and wants to dispel the myth that getting into the U.S. is as simple as filling out a piece of paper and getting on a plane. In fact, less than 1% of all refugees who apply each year are actually resettled.

Luc Dobin ’22, finance chair

The vetting process is lengthy (see sidebar for a full timeline). U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services (USCIS) shares that all refugees must first receive a referral to the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) for consideration, and only then can they receive an application and be interviewed by a USCIS officer who will determine their eligibility for resettlement. Until they are part of this vetting process, refugees are known as asylum seekers.

Sometimes, individuals or families who have been given the green light to resettle in Pennsylvania are able to do so because they already have family here who previously relocated.

“When a refugee is filling out the [application] paperwork overseas, they’ll ask them during the interview if they have family in the United States. After that interview, all of their information is scanned into the system. The file is submitted to us, so that we know if they have family or friends here, and then we can use a contact number or email address to get in touch with them,” explains Tesfu. “If they don’t have any local family, then [volunteers] need to organize everything for when they get here—including transportation, and making sure they get checked out at a medical clinic on day one. That’s required by the government.”

Tesfu is grateful that he’s been able to rely on RefAct members to help navigate and take care of these and other critical tasks that new arrivals face during their first few months of resettlement, including taking care of a new home, language classes, job applications, school enrollment, setting up financial affairs, and introducing them to people who can help them integrate into their new neighborhoods.

“I find the Lafayette students to be so amazing. When we get too many arrivals, we don’t usually have enough help. We always need more volunteers,” Tesfu shares. “The Refugee Action students take care of everything and track everything, so we’re so happy to have their help.”

Maintaining operations through a pandemic

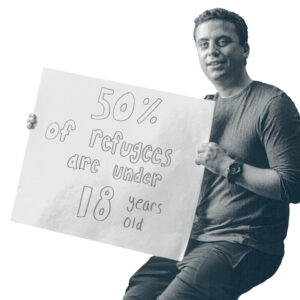

There is a common misconception that “resettling” refugees is simply the process of getting them from the airport to their new residence. There are also common misconceptions that refugees are mostly men, come from the Middle East, are terrorists, and are a drain on society.

As Refugee Action became a campus organization and began to grow over the last several years, it realized early on that educating the public about refugee issues around the globe was an important part of what it hoped to accomplish—that is, that small ways of seeing the “other” in ourselves can make a difference in our approach to complicated problems involving the needs and well-being of people who are in faraway countries.

To that end, the club decided to organize into two very specific areas: events and outreach, and resettlement.

Events and outreach

Prior to the pandemic shifting in-person events in 2020, club members involved in events and outreach would host guest speakers, community dinners, film screenings, virtual reality experiences, fundraising nights, and seek as many opportunities as they could to bring more of their peers into the fold.

When COVID-19 forced events to turn virtual, the club didn’t miss a beat even though everyone was working from a distance. Four films about the global refugee crisis, each highlighting different aspects of a refugee’s journey, were screened online for the Lafayette community. The group also held virtual orientations and hosted Somalian refugee Mohamed Malim for a keynote speech.

Pictured: Jacob Porter, Samantha Ganser, Anastasiia Shakhurina, Katie Kavanagh, Mariama Bah, Anna Boggess, Mackenzi Berner, Lauren Phillips-Jackson, Susanna Hontz, Luc Dobin, Olivia Newman, Eloise Gacetta, Alexa Raxenberg, Lia Sendler, Del Lyczak, Sofia Khalek, Venus Leshaj, Fatma Mahmoudi, Matthew Medaugh, and Celeste Fieberg. Not pictured: Ariel Haber-Fawcett, Nada Awadalla, Mahdia Azizi, Benjamin Falk, Sarah Hawtoff, Deniz Ozbay, Evangeline Coffinas, Melody DiBenedetto, Shirley Liu, and Steph Hotz

This year, RefAct co-hosted (with No Lost Generation at George Washington University) the first-ever National Collegiate Conference on Refugee Advocacy, a two-day (virtual) event connecting like-minded student leaders and professionals on topics related to refugee advocacy. It also co-sponsored Lafayette’s first Migration Summit, a weekend-long online workshop of conversations about what it means to support refugee resettlement and undocumented immigrants through scholarship, activism, and patronage of undocumented-owned businesses. The summit was organized by Flor de Maria Caceres ’22 and Milena Berestko ’22 in collaboration with Refugee Action, Undocufund, and the Hispanic Society of Lafayette.

“When Katie [Katie Kavanagh ’21, RefAct’s president of resettlement] and I were first-years and got involved with RefAct, the club was so new and everyone was making it up as we went, says Lauren Phillips-Jackson ’21, RefAct’s acting president of events and outreach. “As seniors, we have all of these connections across the country, and it feels like our network has really grown. We’ve developed a system that’s really effective. It feels like we’re making connections that we’ll be able to refer back to, and this will allow us even more longevity.”

Resettlement

On a cold Saturday back in February 2021, when snow was still blanketing the Lehigh Valley, members of RefAct’s resettlement team met up to move one of its refugee families from a temporary apartment into a permanent house. While the family had arrived in the area months prior, finding available housing—particularly during the pandemic—had become a challenge. Constant contact had been maintained, however, because the work with a refugee family continues months beyond their arrival on U.S. soil.

For at least six months after refugees resettle here, RefAct helps them with just about every basic necessity one can imagine needing when beginning a whole new life: collecting furniture and home goods, transportation, English tutoring, setting up appointments, teaching finances, enrolling children in school, grocery shopping, and helping them make connections that will integrate them into their new communities. All of these priorities are balanced throughout the day with RefAct members’ own schedules of classes, research and projects, jobs, and extracurricular activities.

“Helping this family get settled into their new home, bringing the truck over, setting up the utilities at the house . . . it felt like going back to the origins of RefAct,” says Kavanagh. “Though some of our members are still across the country doing important work for us in regards to the resettlement, we’re slowly moving toward things hopefully returning to normal next semester.”

Kavanagh also points out how many first-year members of RefAct often start on the resettlement side, and how she’s been impressed by the tasks that many of them have taken on virtually. Whether they’re tutoring both children and adults or even teaching families how to properly read medication bottles, new additions to RefAct who are willing to pitch in and help at any moment are what keep

the organization running smoothly.

“Some of the first-years came in with a lot of experience from tutoring in high school or from working with younger siblings, and they were able to really mesh with some of the families that we work with,” she explains. “I’ve also had a lot of students come in and say, ‘I’m really interested in resettlement, and I don’t know anything about it, but I’m willing to learn,’ and I really appreciate their positive attitudes.”

A team effort

Since the founding of Refugee Action, the club being able to harness a groundswell of support has alleviated pressure on places like Bethany Christian Services and other overstretched providers.

Each academic year, 10 of RefAct’s nearly 30 hard-working members assist Phillips-Jackson and Kavanagh by taking up leadership positions as chairs or coordinators for specific responsibilities: Anna Boggess ’23 is the acting events chair; Samantha Ganser ’23 is the acting outreach chair; Ariel Haber-Fawcett ’24 is the acting case management committee chair; Ben Falk ’23 is the acting accommodations committee chair; Fatma Mahmoudi ’22 is the acting education committee chair; Luc Dobin ’22 is the acting finance committee chair; Olivia Newman ’22 is the acting transportation coordinator; Sarah Hawtof ’21 is the acting furniture coordinator; Anastasiia Shakhurina ’22 is the acting treasurer; and Nada Awadalla ’23 serves as housing coordinator.

With each of these volunteers being drawn on for specific tasks, they offer unique perspectives into how being part of RefAct has affected them.

Anna Boggess ’23, events chair, holds “welcome” sign written in Farsi.

“For someone who doesn’t understand refugees, I would tell them to think about this process as if it’s one of your best friends or family members going through it,” says Ganser, who grew up in the Lehigh Valley and got involved because of the local refugee and immigrant population. “There are so many people who don’t understand people of other cultures, and they tend to dehumanize them. So, when you read or learn about refugee experiences, think about your best friends and your family, and what kind of services you would want for them.”

“The actual systematic way that the U.S. government has set up the refugee system is completely dependent on volunteers or completely dependent on local agencies finding volunteers. Otherwise, this work would not be possible,” points out Haber-Fawcett. “When refugees arrive, they are given a caseworker for 90 days, and $925 each. Helping them is an incredibly challenging experience, but it’s a rewarding experience.”

“I feel like when these students graduate, they should have a master’s in social work because they’ve learned so much,” says Hendrickson. “From the beginning, the students who have been part of RefAct have really taken charge and have said, ‘We’re going to do something that really makes a difference.’ It’s also given them a whole new perspective.”

Raising the ceiling

With a high number of migrant children held at the U.S./Mexico border over the past several years, the U.S. government has inched its way toward the promise of a raised ceiling of allowing at least 62,500 refugees into the country during the 2021 fiscal year. As a result of the long delays, many lives have been left in limbo.

Both Tesfu and Helwig explain that they have had families scheduled to arrive in the U.S. earlier this spring whose clearances were only valid until their travel-by dates, which means that they will have to begin the process over.

“We had two families identified for resettlement, their flights were booked, and they were scheduled to arrive. But because their flights were canceled, and because the presidential determination had not been signed at that point, those families were not able to be resettled here,” explains Helwig.

It is because of setbacks like this that RefAct members will continue to fight for, and act as voices for, those who cannot fight and speak for themselves.

How you can help

Because of the constant need for physical household goods and items of clothing for the incoming families, RefAct’s resettlement team will often communicate internally (via a monthly club newsletter) or externally (sharing flyers on campus or emails to community partners) about what current needs are in terms of donations. Those needs can range from twin mattresses, to microwaves, to shoes and clothing items. At this stage, four years into RefAct’s still-young existence, the group has been able to rely on community partners, as well, to help cross items off its wish lists.

Those partners can include professors from other colleges and universities, business owners, or people with special skill sets who heard about RefAct from a friend, colleague, or neighbor.

“There’s no way we’d be able to function the same way we do without community support, especially during the pandemic,” says Kavanagh. “We’ve gotten people from all over the Lehigh Valley who are willing to help out, even though most of the refugees who come here are settled in Allentown, and we’re based in Easton. Word of mouth has helped us expand our reach, and we’re grateful for that interest and that strong support.”

There are many ways you can support Refugee Action. Email refact@lafayette.edu to join its mailing list to receive monthly updates, including ways you can help with outreach, resettlement, in-kind donations, and monetary donations. The group also provides a number of educational resources and information on how you can contact your state representatives to encourage refugee support.

The step-by-step process of resettlement

For those refugees who are going through the system, here are steps they must take, according to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS):

Step 1: Refugees become known to humanitarian officials through visits that happen over a certain period of time—often years—before they are even selected for consideration. Typically, there are multiple visits to ensure their claims are valid.

Step 1: Refugees become known to humanitarian officials through visits that happen over a certain period of time—often years—before they are even selected for consideration. Typically, there are multiple visits to ensure their claims are valid.

Step 2: Once a refugee’s situation merits resettlement consideration, a UNHCR staff person conducts interviews and builds an in-depth file on this refugee. For humanitarian officials engaged in the process, there is anti-fraud training that tests whether the refugee’s story will hold up. There is significant scrutiny for each individual and family.

Step 2: Once a refugee’s situation merits resettlement consideration, a UNHCR staff person conducts interviews and builds an in-depth file on this refugee. For humanitarian officials engaged in the process, there is anti-fraud training that tests whether the refugee’s story will hold up. There is significant scrutiny for each individual and family.

Step 3: A U.S. embassy or processing contractor receives the file on the individual or family, and the American part of the process begins. This includes new rounds of face-to-face interviews where they learn the refugee’s story of persecution and other personal details.

Step 3: A U.S. embassy or processing contractor receives the file on the individual or family, and the American part of the process begins. This includes new rounds of face-to-face interviews where they learn the refugee’s story of persecution and other personal details.

Step 4: Extensive security checks happen. This includes fingerprinting and photos, as well as security checks done by the DHS, the National Counter-terrorism Center, the FBI’s Terrorist Screening Center, the Department of Defense. During this time, the refugee(s) under consideration do not know how their cases will be resolved.

Step 4: Extensive security checks happen. This includes fingerprinting and photos, as well as security checks done by the DHS, the National Counter-terrorism Center, the FBI’s Terrorist Screening Center, the Department of Defense. During this time, the refugee(s) under consideration do not know how their cases will be resolved.

Step 5: The DHS sends out a specially trained refugee corps officer to conduct an intensive adjudication interview.

Step 5: The DHS sends out a specially trained refugee corps officer to conduct an intensive adjudication interview.

Step 6: If the individual is approved for resettlement, there are medical examinations, cultural orientation classes, and other processing steps before the individual can travel to the U.S.

Step 7: From the point of referral to departure, the process takes an average of several years. During this time, if any additional or contradictory information comes to light, the case can be put on hold or the approval can be revoked. There is also a final security check upon arrival at a U.S. airport.

Step 7: From the point of referral to departure, the process takes an average of several years. During this time, if any additional or contradictory information comes to light, the case can be put on hold or the approval can be revoked. There is also a final security check upon arrival at a U.S. airport.