In the Marquis’ Footsteps

Unlike his stops in other states, his visit to Louisiana helped validate the territory’s admittance to the Union, as many people had opposed inclusion because of its French background, a result of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. When Lafayette first arrived aboard the steamboat Natchez April 10, 1825, hundreds of men in French uniforms greeted the nation’s guest on the banks of the Mississippi River with whoops of Vive la liberté! Vive l’ami de l’Amérique! Vive Lafayette! He was then accompanied by a military escort to Chalmette battlefield, site of the Battle of New Orleans, where a decisive victory over the British had taken place. There, during his opening remarks, Lafayette took the opportunity to reinforce that Louisiana was no longer a foreign region but an integral part of the United States. During his five-day visit, a street and a square were named in his honor, followed by a cemetery a few years later.

In this issue, we trace the famous Frenchman’s journey through magnolia trees, spooky crypts, and a city hall turned museum where Lafayette once slept.

For more information, visit thelafayettetrail.com, which was created by Julien Icher.

1. Théâtre d’Orléans

717 N. Orleans St.

bourbonorleans.com

There were actually two theaters in New Orleans in 1825. One performed shows in English, the other in French, and they competed against one another for patrons. Pressed to visit both theaters on the same night, Lafayette decided by lot which one to visit first, and chance favored the English, called Camp Street Theatre, run by James Caldwell. Lafayette arrived there at 7 p.m. and afterward made his way to Théâtre d’Orléans on Orleans Street where he caught the last act of a vaudeville titled Lafayette in New Orleans.

There were actually two theaters in New Orleans in 1825. One performed shows in English, the other in French, and they competed against one another for patrons. Pressed to visit both theaters on the same night, Lafayette decided by lot which one to visit first, and chance favored the English, called Camp Street Theatre, run by James Caldwell. Lafayette arrived there at 7 p.m. and afterward made his way to Théâtre d’Orléans on Orleans Street where he caught the last act of a vaudeville titled Lafayette in New Orleans.

Both theaters burned down and were rebuilt and renamed several times over the years, but the Civil War was more devastating than fire to the city’s nightlife. In 1881, the French theater and adjacent ballroom were acquired by the first female-led African American order of nuns. The sisters founded an orphanage, church, and school on the property but outgrew the complex in the 1960s. Construction began on the Bourbon Orleans Hotel in 1964, and the original ballroom was restored to its grandeur and is now in use for weddings, banquets, and special occasions.

Both theaters burned down and were rebuilt and renamed several times over the years, but the Civil War was more devastating than fire to the city’s nightlife. In 1881, the French theater and adjacent ballroom were acquired by the first female-led African American order of nuns. The sisters founded an orphanage, church, and school on the property but outgrew the complex in the 1960s. Construction began on the Bourbon Orleans Hotel in 1964, and the original ballroom was restored to its grandeur and is now in use for weddings, banquets, and special occasions.

The site of the original Camp Street Theatre is now a parking lot.

You don’t have to go to New Orleans to hear this Lafayette, La., band jam, as you can access its music on YouTube and Amazon, but you might be able to catch one of its concerts if you’re in the Big Easy or even elsewhere as it sometimes goes on tour. Its second album is called The Lafayette Marquis, and the band’s blend of steamy blues and Cajun rock could serve as theme music when tracing the real Lafayette’s journey through the cobblestone streets of the French Quarter on which Lafayette slept.

You don’t have to go to New Orleans to hear this Lafayette, La., band jam, as you can access its music on YouTube and Amazon, but you might be able to catch one of its concerts if you’re in the Big Easy or even elsewhere as it sometimes goes on tour. Its second album is called The Lafayette Marquis, and the band’s blend of steamy blues and Cajun rock could serve as theme music when tracing the real Lafayette’s journey through the cobblestone streets of the French Quarter on which Lafayette slept.

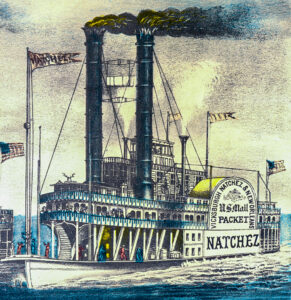

2. Steamboat Natchez

400 Toulouse St.

steamboatnatchez.com

A steamboat bearing the name Natchez, like the one that bore Lafayette up the mighty Mississippi River from Mobile, Ala., to New Orleans, is now a tourist attraction, offering dinner and day jazz cruises from the heart of the French Quarter. Set sail for a two-hour guided tour of historical river sites while listening to Dukes of Dixieland, one of the hottest jazz bands in New Orleans.

A steamboat bearing the name Natchez, like the one that bore Lafayette up the mighty Mississippi River from Mobile, Ala., to New Orleans, is now a tourist attraction, offering dinner and day jazz cruises from the heart of the French Quarter. Set sail for a two-hour guided tour of historical river sites while listening to Dukes of Dixieland, one of the hottest jazz bands in New Orleans.

Natchez has had as many lives as a cat. The original one was built in New York City in 1823, but fire destroyed her in 1835. Since then, there have been eight Natchez boats with the latest created in 1975 by New Orleans Steamboat Company as one of only two steam-powered sternwheelers working the Mississippi today. Boarding the Natchez makes you feel like you’ve entered another era as the captain barks orders through a hand-held megaphone, and the 25-ton white oak wheel churns the choppy waters of the timeless river.

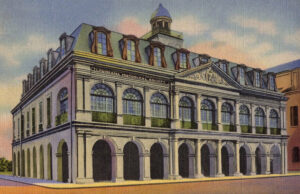

3. Louisiana State Museum

701 Chartres St.

louisianastatemuseum.org/museum/cabildo

Lafayette lodged for five nights at the Cabildo, which at the time served as the center of New Orleans government. City council chambers were converted to Lafayette’s quarters and outfitted with fancy furniture, rugs, drapes, and chandeliers borrowed from wealthy residents. “They figured it would be grand and important enough to welcome him,” says Karen Leathem, historian of the Louisiana museum.

Lafayette lodged for five nights at the Cabildo, which at the time served as the center of New Orleans government. City council chambers were converted to Lafayette’s quarters and outfitted with fancy furniture, rugs, drapes, and chandeliers borrowed from wealthy residents. “They figured it would be grand and important enough to welcome him,” says Karen Leathem, historian of the Louisiana museum.

In 1853, the Cabildo became headquarters of the Louisiana State Supreme Court, where in 1892 the infamous “separate but equal” Plessy v. Ferguson decision originated. In 1908, the building became home to Louisiana State Museum, and a bronze bust of Lafayette graces its first floor.

4. Jackson Square

751 Decatur St.

neworleans.com/listing/jackson-square/32150

A parade led Lafayette to Place d’Armes, now known as Jackson Square, where a temporary triumphal arch was built in his honor. The base of the nearly 70-foot-high arch was formed from green Italian marble, and its curves were composed of 24 stones, each decorated with a gilded star to signify the 24 states of the Union. Lafayette, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and names of officers who distinguished themselves during the Revolutionary War embellish the monument. Located in the heart of the French Quarter, the park was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1960 for its role in the city’s history, and as the site of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Today, the square hosts art shows, celebrations, and live music events.

A parade led Lafayette to Place d’Armes, now known as Jackson Square, where a temporary triumphal arch was built in his honor. The base of the nearly 70-foot-high arch was formed from green Italian marble, and its curves were composed of 24 stones, each decorated with a gilded star to signify the 24 states of the Union. Lafayette, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and names of officers who distinguished themselves during the Revolutionary War embellish the monument. Located in the heart of the French Quarter, the park was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1960 for its role in the city’s history, and as the site of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Today, the square hosts art shows, celebrations, and live music events.

5. Lafayette Cemetery #1

Washington Avenue

freetoursbyfoot.com/lafayette-cemetery-1-new-orleans/

Planning of this cemetery began in 1833 in preparation for the creation of Lafayette City, now known as the Garden District. The size of a city block, the cemetery features a maze of above-ground Gothic tombs and mausoleums and is the most filmed graveyard in New Orleans. It also was the inspiration for author Anne Rice’s novel Interview with a Vampire, later made into a movie and filmed there. Today the cemetery is still in use and contains 1,100 family tombs and 7,000 people. You can take a self-guided tour or hop on a bus that includes a stop at the cemetery.

Planning of this cemetery began in 1833 in preparation for the creation of Lafayette City, now known as the Garden District. The size of a city block, the cemetery features a maze of above-ground Gothic tombs and mausoleums and is the most filmed graveyard in New Orleans. It also was the inspiration for author Anne Rice’s novel Interview with a Vampire, later made into a movie and filmed there. Today the cemetery is still in use and contains 1,100 family tombs and 7,000 people. You can take a self-guided tour or hop on a bus that includes a stop at the cemetery.