A Complicated Legacy

Over the summer, as Confederate and other statuary fell across the nation in response to George Floyd’s death, Arleen Fields held her breath, hoping that a monument in Cross Creek Park in Fayetteville, N.C., would be spared.

“We’ve really upped our promotion of the Marquis de Lafayette as a champion of human rights,” said Fields, secretary of the Lafayette Society in Fayetteville, which raises awareness of the young French nobleman’s contributions to American freedoms. “We have a statue of him downtown, and we don’t want people tearing him down thinking he’s one of the bad guys.”

So far, Fayetteville’s edifice to its namesake—Fayetteville is the only U.S. city the Marquis actually visited that bears his name—and that of Lafayette College have remained untouched.

Appearing in full military uniform, a sword at his side, the bronze and granite depiction of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette is the one perhaps most familiar to Americans as the dutiful teenage major general who served in the Continental Army under George Washington.

But he left another legacy—his stubborn push to end slavery and advocate for human rights and dignity. Inspired by his friendship and service with African Americans during the Revolutionary War and his devotion to the ideals of the Enlightenment and those expressed in the Declaration of Independence, his human rights work began in earnest soon after his military service in America and return to France.

“It’s a complicated legacy, because he very much wanted to stay within the laws as they were written at the time, which were decidedly pro-slavery, but also work to change the laws through personal lobbying,” says Robert Taber, a history professor at Fayetteville State University, who specializes in the history of slavery, race, and family life in French colonies during Lafayette’s time.

Jacques Nicholas Bellin. Carte de la Guyane. Engraved map, hand-colored, 1757. David Bishop Skillman Library, Lafayette College

Perhaps his boldest idea, an experiment designed to gradually free enslaved people, is largely obscured by his larger than life image as a military leader. In 1785, Lafayette purchased two plantations in the French colony of Cayenne, now French Guiana, on the northeastern coast of South America. With them came 70 enslaved people whom Lafayette began to pay and provide schooling for their work in preparation for their freedom.

In a February 1783 letter (owned by Lafayette College) to his old friend and comrade, Lafayette invited Washington to join him in the plan.

“Now, my dear General, that you are going to enjoy some ease and quiet, permit me to propose a plan to you which might become greatly beneficial to the Black Part of Mankind. Let us unite in purchasing a small estate where we may try the experiment to free the Negroes, and use them only as tenants—such an example as yours might render it a general practice, and if we succeed in America, I will cheerfully devote a part of my time to render the method fashionable in the West Indies. If it be a wild scheme, I had rather be mad that way, than to be thought wise on the other tack.”

Washington politely demurred in his reply a few months later, characterizing Lafayette’s plan as striking evidence of “the benevolence of your Heart. I shall be happy to join you in so laudable a work; but will defer going into a detail of the business, till I have the pleasure of seeing you.”

Mary Thompson, research historian at George Washington’s Mount Vernon, speculates that Lafayette’s visit to Mount Vernon a year later in 1784 might have contributed to Washington’s evolving view on slavery and influenced his eventual decision to make provisions in his will to free his enslaved people.

“You can imagine the conversations they had that we don’t know about while talking on the piazza at Mount Vernon or riding around together on the estate,” she says. “Lafayette likely talked about the hypocrisy of fighting for liberty and freedom, while keeping others enslaved, and shared his hope that, if it was successful, his idea of gradual emancipation would spread to the West Indies and other parts of the world.”

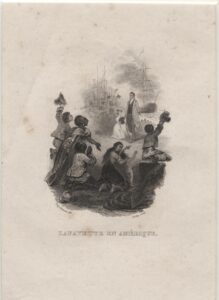

Jean-Jacques Frilley, after Tony Johannot. Lafayette en Amerique. Engraving. Paris: Perrotin, n.d. David Bishop Skillman Library, Lafayette College

While Lafayette was imprisoned in Prussia in 1792 after fleeing radical revolutionaries in France, his Cayenne property was seized and his Black tenants eventually returned to a state of slavery when Napoleon reinstituted slavery in the French colonies in 1802.

Under the cultural lens of 21st-century sensibilities, his scheme might seem like little more than a continuation of a form of bondage and servitude. But, as Lafayette expert Lloyd Kramer points out, Lafayette’s actions were radical by late 18th-century standards, embraced by progressives seeking an end to slavery.

“It’s easy to say in hindsight that it was a flawed strategy and didn’t lead to much,” says Kramer, history professor at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “But I really do believe he was sincere in his thinking that this was the way to end slavery.

“People often say that he was a naive idealist about almost everything,” he adds. “But he also was pragmatic in the sense that he said, well, if you have had no freedom and no training, how are they going to survive economically without education?”

Lafayette’s idea didn’t die with the French Revolution.

His good friend, Scottish-born American political activist Fanny Wright, followed the retired general during part of his farewell tour of the United States (1824-25), discussing emancipation with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison along the way.

A daughter figure to Lafayette, Wright confronted Jefferson repeatedly over the issue of slavery and came up with a plan to buy a plantation near Memphis, Tenn., to educate and emancipate enslaved people. She raised money from abolitionists, including Lafayette, and replicated in the 1820s what Lafayette tried in the 1780s.

At the settlement, called Nashoba, she brought together whites and Blacks and faced withering criticism by mixing races.

“The experiment ultimately collapsed,” Kramer says. “But she had the same idea of training these people with the goal that, one by one, they’d be freed. Although her plan unraveled, she managed to help 30 people escape from slavery by moving them to Haiti to secure their freedom.”

When Lafayette, his head swirling with visions of battlefield glory, sailed to America in 1777 to join the patriot cause, he likely had no position on the slave trade.

“I don’t think he could have had much of an opinion before that time. I mean, he was only 19 years old when he arrived,” says Alan Hoffman, president of the Massachusetts Lafayette Society and the Lafayette College-based American Friends of Lafayette, a national organization dedicated to the memory of Lafayette and the study of his life and times in America and France.

But that quickly changed when he encountered, befriended, and fought the British with African Americans who served at his side.

He commanded troops in the all-Black First Rhode Island Regiment in defense of Bristol and Warren, R.I., in September 1778, and later served with them during the siege of Yorktown, befriending an enslaved African American, James Armistead, who spied on Cornwallis and delivered valuable intelligence to the combined American and French forces. Despite his bravery and patriotism, Armistead was returned to slavery after the war until Lafayette’s personal lobbying won his freedom.

“Lafayette’s antislavery advocacy continued until the end of his life,” Hoffman says. “During his final visit to America in 1824 and 1825, he pointedly sought out African Americans, visiting the African Free School in New York City and clasping hands with African American veterans of the War of 1812 in New Orleans, for example.”

Lafayette’s strides to help end the slave trade and slavery itself constituted just one part of his social justice persona. He helped write the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Men and of the Citizen, supported Native Americans, defended the rights of French Huguenots and Jews before and during the French Revolution, backed national revolutions in Europe and South America, spoke out against capital punishment and solitary confinement, and supported women and their ideas and causes.

In 2016, the story of Lafayette’s role as an international antislavery advocate was the subject of an extensive exhibition at the Grolier Club in New York, curated by Lafayette College’s Olga Anna Duhl, Oliver Edwin Williams Professor of Languages, and Diane Windham Shaw, director emerita of Special Collections and College Archives. The exhibition was accompanied by a beautifully illustrated catalog, “A True Friend of the Cause”: Lafayette and the Antislavery Movement.

“It has long been my desire for people to know Lafayette in a broader sense,” Shaw says. “I think Lafayette would have a lot to say about the state of America today and what is needed. He had a vision for America—as a haven for virtue, integrity, tolerance, equality, and liberty—that we would do well to adhere to today.”

When Lafayette returned to America for the last time in 1824, he sought Black Americans who served with him and Washington during the war, “a terrible problem for his hosts in the United States,” Taber says.

“The big life lesson to take from Lafayette is to not give up the fight for human rights,” he says. “Never give up the fight for justice, equality, and equity. Stay committed, even when things don’t necessarily go your way, when things don’t necessarily look exactly how you want them to, but keep fighting for your ideals.”