Jan 11, 2013

A Range of Choices

Additional research opportunities include: Research Assistants Pilot Program, launched 2010-11; students apply disciplinary skills to assist faculty with…

Alexandria Brannick ’12 (left) and Jaclyn White ’13

scour rock piles in Sutton, Alaska, looking for leaf

fossil specimens during a research trip last summer.

by Samuel T. Clover ’91

Nearly 25 percent of Lafayette students conduct substantive basic research at some point during their four years. The College’s focus on close student-faculty interaction has made it a national leader in undergraduate research. Guided by faculty members, students who participate in these programs often publish their work in academic journals, present at regional and national conferences, or conduct research in off-campus field locations.

Some of these students complete creative projects such as a series of paintings, a musical composition, a novel, or a theatrical script. Their experience makes them successful candidates for national scholarships and fellowships, and many are accepted into some of the country’s top graduate programs.

Having the opportunity to work one-on-one with a professor as an undergraduate is unique to small liberal arts colleges, since these opportunities go to graduate students at universities and colleges that grant graduate degrees. At Lafayette, the opportunities are further enhanced by the presence of the engineering division.

The cornerstone of student-faculty research is the EXCEL Scholars program in which a student works collaboratively with a faculty member on his or her ongoing research. Students who prefer a more self-directed approach may choose a topic that interests them and, working with a faculty adviser, conduct a semester-long independent study or a yearlong honors thesis project. Many other opportunities are offered as well (see “A Range of Choices,” page 31).

Elaine Reynolds, associate professor of biology, and Glenford Robinson ’13 are using epileptic flies to try and understand why a high-fat diet reduces the incidence of seizures in some people.

Each year, approximately 250 students in all four academic areas — natural sciences, social sciences, humanities, and engineering — are nominated by their professors to be EXCEL Scholars. Once approved by the Academic Research Committee, composed of faculty members from each division, students are paid $8 to $10 per hour for a maximum of 10 hours per week during the academic year. Some conduct research full-time during January interim or over the summer.

One student who has taken advantage of both the EXCEL Scholars program and honors research is Alexandria Brannick ’12, a geology major. Accustomed to rigorous schedules — as co-captain of Lafayette’s swimming and diving team, she typically trains two hours a day, six days a week — her research trip to Alaska for two weeks last July posed unique challenges. She was part of a team that included her adviser, David Sunderlin, assistant professor of geology and environmental geosciences and a paleontology specialist, and Jaclyn White ’13.

The extended northern daylight meant long days of scouring rock beds for leaf fossil specimens, which they would then clean, examine, and organize. Since the weather was unpredictable, sometimes bringing three or four days of cool, steady drizzle, they took full advantage of clear days to get as much fieldwork done as possible.

“Undergraduate research is an integral part of this community,” says John Meier, associate provost for faculty development and research services, and professor of mathematics. “It is a natural outgrowth of having excellent students on campus who interact on a daily basis with faculty who are producing very interesting scholarly work. This sort of student-faculty interaction isn’t just valued; it is a deeply embedded part of our identity.”

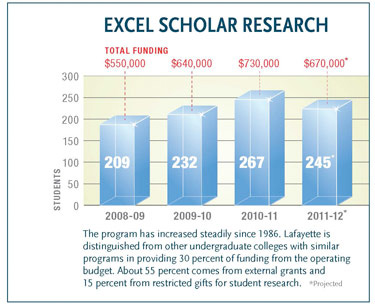

The program, which began in 1986 with 14 students, has grown steadily in numbers, stature, and credibility. The number of students has doubled in the past 10 years, from 112 in 2000-01 to 267 in 2010-11 (see chart below).

One mark of that success is that each spring for the past 25 years, students have been invited to present their work at the National Conference on Undergraduate Research. This year, 25 students will present at the conference being held in March at Weber State University, Ogden, Utah. “We could probably send twice as many students if we had a more generous budget,” says Meier. “While other small colleges have similar programs, Lafayette usually has the largest representation. We are a leader in this arena.”

Approximately 2,200 undergraduates from more than 250 colleges and universities attend NCUR.

“Lafayette students do an excellent job of presenting their work,” he says. “But, I am most impressed by the research skills and instincts they display during the conference when they aren’t presenting. They are an intellectually curious group, going to talks and poster presentations, thinking about their peers’ work, and coming up with insights, new directions that could be explored, and spotting diffi culties in methodology. Those are not the sort of analytic skills one develops without having the intense, focused experience of working with faculty on research projects.”

“Lafayette students do an excellent job of presenting their work,” he says. “But, I am most impressed by the research skills and instincts they display during the conference when they aren’t presenting. They are an intellectually curious group, going to talks and poster presentations, thinking about their peers’ work, and coming up with insights, new directions that could be explored, and spotting diffi culties in methodology. Those are not the sort of analytic skills one develops without having the intense, focused experience of working with faculty on research projects.”

Among this year’s presenters is Ericka “Missy” Chehi ’12, an economics and Asian studies double major. She will present “China’s Household Registration System: The Effects of Hukou on China’s Current Generation,” based on her honors thesis research advised by Robin Rinehart, professor and head of religious studies and chair of Asian studies.

Each honors project is guided by a faculty member. Students register for a fall and spring thesis course, conduct research, and write the thesis. Much like graduate school, the student defends the thesis before a committee that includes his or her mentor, departmental faculty members, and in some cases, an outside faculty member. An average of 63 students each year graduate with honors.

Chehi’s interest in China began with a three-week visit during high school. Upon arriving at Lafayette, she began taking Chinese courses and spent her entire junior year abroad in Shanghai and Beijing to study recent reforms in the Chinese economy and politics. During her stay she interviewed some of the floating population of street vendors and retail workers who had illegally moved from villages to cities to cash in on growing urban prosperity.

The hukou system of household registration links people with the region in which they were born and determines what kind of social services they receive. It also restricts rural-to-urban movement, since cities are overcrowded.

“People who have an urban registration receive education, job opportunities, health care. Rural people don’t have these and are not allowed to move to urban areas,” Chehi explains. “One man in Beijing hadn’t seen his family for years. He had come to the city by himself and was working as a bicycle rickshaw driver. This allowed him to send money to his family so they could keep their land in their home village.”

Rinehart says honors theses enable students to experience an integration and depth of learning not available in regular courses. As an adviser, she guides them in “how to think through an issue on their own, figure out the most effective ways to do research, and learn how to craft their own analysis and not just summarize what others have said or written.” An honors thesis takes their research work and analytical ability to a higher level.

“The biggest challenge is that they’ve never written or conceived of such a lengthy project,” Rinehart says. “It’s daunting to think about what is realistic to cover, how to find enough sources, and how to organize it.” Faculty mentors teach students to work independently and to develop a work ethic to check their progress because there is no syllabus to follow.

The relationship is based on guidance and collaboration says David Sunderlin, faculty adviser for Brannick’s honor thesis.

As often occurs, Brannick’s involvement in Sunderlin’s research led her to develop an interest in a related topic. She is exploring Alaskan fossil records of herbivory intensity and diversity — that is, the way ancient insects ate plants — to gain insight into the way ecosystems may have functioned in the Paleocene-Eocene epochs.

Brannick previously learned how to examine plant fossils using samples at Lafayette. She took photographs and then reproduced them using a computerized drawing program in order to calculate the frequency of insect damage. “This taught her the methods and analyses that are done so that she would be able to apply them to a fresh set of data,” says Sunderlin.

Susan Averett (left), Dana Professor of Economics, Andrew Holmes ’12, and George Bright, associate director of athletics, discuss sports management in a seminar room in Allan P. Kirby Sports Center.

“What’s great about my thesis is that I can contribute my ideas,” says Brannick. “It’s more of a conversation, trying to figure out what’s going on with these fossils instead of just being a student. My input has value. I’m actually contributing to the questions posed in this research area. I think that’s the point of doing a thesis.”

Sunderlin agrees. “I am not handing down a task, and then the student does it. They come up with their own tasks to answer questions that they have about the science themselves.”

In weekly meetings, they discuss how scientific writing is done. Brannick brings drafts, and Sunderlin provides a critique, helping her determine how to incorporate something new learned from the material into the thesis. “Science is done in this iterative fashion,” he says. “Her project has implications for how climate and ecosystems are working in concert and is directly related to paleontology, which she plans to study in graduate school.”

Another student who is excited to conduct in-depth research on a topic related to his future plans is Glenford Robinson ’13, a neuroscience major who plans to attend medical school. He is one of eight students currently conducting research in the lab of Elaine Reynolds, associate professor of biology and a neuroscientist. He is assisting her with a study that uses epileptic flies to try and understand why a high-fat diet reduces the incidence of seizures in some people.

“There’s potential for development of a new drug,” says Reynolds, who has worked with more than 70 students over the past 14 years on projects ranging from the genetics of alcoholism and epilepsy, to computer modeling of neurocomplexity.

Ericka Chehi ’12 (right) discusses China’s hukou system, the topic of her honors thesis, with adviser Robin Rinehart, professor of religious studies and chair of Asian studies.

The ketogenic diet reduces the number of seizures in people who don’t respond to drugs. A previous student looked into the ratio of protein to carbohydrate to fat, to see if a particular ratio could reduce seizures. “We found several diets that did reduce and prevent seizures,” says Reynolds. “Glen is working to better define what components of the diet are important in modulating the seizure in the fly model of epilepsy.”

Some students, like government and law major Andrew Holmes ’12, prefer to design their own independent study rather than delving into EXCEL research or an honors thesis.

Interested in the effects of European and American colonialism, particularly on Africa and countries of the African diaspora, Holmes turned to John McCartney, professor of government and law, who grew up in the Bahamas and has “a vast knowledge of the field,” Holmes says. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, McCartney was president of the Vanguard Party in the Bahamas and ran for the Bahamian parliament.

“I was excited about Andrew’s interest in third-world countries,” says McCartney. “His father is from Jamaica, and his mother is from the U.S. He knows his background, but wanted to learn more about the other side.”

In the fall, Holmes studied the 1963 revolution in Kenya and the life of Jomo Kenyatta, the country’s first prime minister and president. The work prepared him for the January study-abroad course in Kenya where he studied politics and history with Rexford Ahene, professor of economics and chair of Africana Studies.

Currently, Holmes is exploring the dynamics of sports management and the importance of athletics to an academic community. His advisers are Susan Averett, Dana Professor of Economics, and George Bright, associate director of athletics.

“I feel there is wealth of valuable knowledge to be discovered about the management side of athletics that would balance my experience on the field,” says Holmes, who completed his final season as a defensive lineman on the football team. “With my knowledge as a varsity athlete, I feel I can offer a new perspective for the department, and the department will do the same for me.”

McCartney is also intrigued by Holmes’s ability to balance his responsibilities as an athlete and student. McCartney should know: he himself once managed an amateur baseball team in the Bahamas, the City Lumberyard Baseball Club. It’s another example of the serendipity that happens when students and professors work so closely together.

Additional research opportunities include: Research Assistants Pilot Program, launched 2010-11; students apply disciplinary skills to assist faculty with…

A nationwide trend in undergraduate research has been that projects tend to be focused on and largely defined by scientific research more so than research…

Faculty have collaborated with students on their scientific research from at least the early 1900s, beginning with Beverly W. Kunkel, professor of biology…