Home Sweet Home

Caitlin Flood ’12 co-founds organization that gives struggling families a fresh start

Domestic violence is one of the primary causes of homelessness for women and their children in the United States.

According to the National Network to End Domestic Violence, between 22 and 57 percent of women and children are homeless due to domestic violence, with 38% of all victims experiencing homelessness at some point in their lives due to domestic violence.

In the U.S., female adults, youth, and children comprise 38% of those experiencing homelessness, with adult women and female youth making up 29%, or nearly one-third.

When victims of domestic violence choose to leave their abusive partner, safe and affordable housing may become one of the primary barriers they will face for themselves and their family. Intimate partner violence is a cycle that often includes severing ties to resources such as community support and financial access. In these circumstances, options can narrow very quickly to emergency shelter and the hope for transitional housing.

Without these programs, survivors have no options other than to return to their abuser’s home or face homelessness. And very often, the networks that are built to provide transitional or safe housing include everyday, ordinary people who just want to extend a helping hand. Very often, these angels are volunteers who have full-time jobs, families of their own, and utilize their precious spare time to help those in need.

April Hinkle (left) and Caitlin Flood ‘12 (right) provide help, support, and homes for vulnerable community members.

Caitlin Flood ’12 is one of those people who has seen injustice firsthand and knew she had the power to make a difference.

After law school, Flood worked as an assistant deputy public defender for the Office of the Public Defender in New Jersey. For the past two years, she has served as a senior program manager on the National Training and Technical Assistance team at the Center for Court Innovation, providing criminal justice practitioners technical assistance in creating and enhancing community courts.

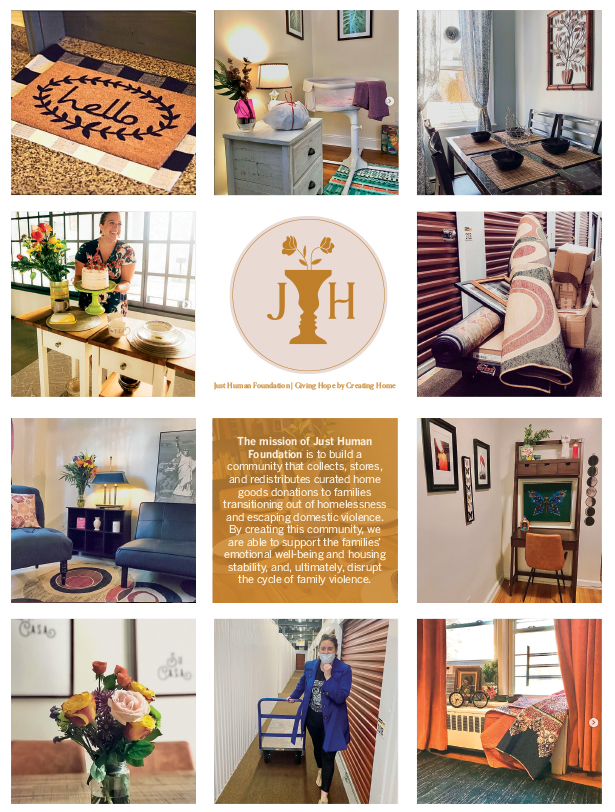

On top of all that, Flood managed to find the time to co-found Just Human, an organization that collects, stores, and redistributes curated home goods donations to families facing housing insecurity. Just Human not only provides a direct service to these families, but also connects them with donors in a larger community, where those donors can see the impact of their contributions in real time.

The story began when Flood met her co-founder, April Hinkle, when they were both assisting a reentry nonprofit in New York. In November 2019, Hinkle reached out with an idea she had been brainstorming for years. After becoming a new mother herself and thinking about the challenges families face raising children with limited means, Hinkle wondered what it would look like if she and Flood collected gently used home goods and then connected with families who were moving out of shelters.

Hinkle worked in the social services field since 2014, and at the time Just Human was started, she was the manager of a crime victim services agency that is well known for working with survivors of domestic violence. Her knowledge of domestic violence services and homeless shelters was integral to creating Just Human’s mission of helping families create a warm and welcoming home when transitioning to a new space.

Hinkle worked in the social services field since 2014, and at the time Just Human was started, she was the manager of a crime victim services agency that is well known for working with survivors of domestic violence. Her knowledge of domestic violence services and homeless shelters was integral to creating Just Human’s mission of helping families create a warm and welcoming home when transitioning to a new space.

“When I was working with Safe Horizon, a victims’ service agency in New York City, I was constantly hearing about families needing to find safe housing options while weighing the needs of their children,” explains Hinkle. “This included toys, clothing, school supplies, and home comforts all being weighed against their own safety. This was the catalyst for the creation of Just Human.”

While it was nice for them to have a coffee table and pictures and art hanging, what they also needed was a bed, a couch, and a kitchen table where their kids could do homework.

co-founder of Just Human

The two women laid out a plan, but there were questions that needed to be answered. How would they find the families in need? And how long would it take—with the women each working full-time jobs—to get a volunteer-based organization off the ground in Hudson County?

“April was living in New Jersey and reached out to the housing provider Women Rising, which does a lot of work around domestic violence services and setting people up with emergency housing and permanent housing,” recalls Flood. “Once we had our first referral partner, we were able to connect with families who were transitioning, specifically from domestic violence shelters.”

Hinkle set up a social media presence asking donors for items that would help families make a fresh start—everything from end tables to rugs and mirrors—and the immediate response was overwhelming.

“It branched off into donations of much bigger furniture, because what we were learning was that a lot of our families that were coming from shelters had almost nothing,” Flood explains. “While it was nice for them to have a coffee table and pictures and art hanging, what they also needed was a bed, a couch, and a kitchen table where their kids could do homework.”

“It branched off into donations of much bigger furniture, because what we were learning was that a lot of our families that were coming from shelters had almost nothing,” Flood explains. “While it was nice for them to have a coffee table and pictures and art hanging, what they also needed was a bed, a couch, and a kitchen table where their kids could do homework.”

The donation of larger items filled up one storage unit in New York, and then another in New Jersey. The women helped do one apartment setup, and then another and another—each time, tagging their furniture donors in social media posts that showed new homes ready to welcome families. Through the Instagram page, donors get to see their former belongings in people’s new homes.

It was February 2020. Just Human was moving full steam ahead and had completed four apartment setups in just two months. And then, COVID-19 hit.

A Pandemic Within a Pandemic

Throughout spring, summer, and fall of 2020, the news headlines went out around the world.

In The New York Times: “A New COVID-19 Crisis: Domestic Abuse Rises Worldwide.”

In The Washington Post: “For Women and Children Around the World, a Double Plague: Coronavirus and Domestic Violence.”

On CNN: “The Shadow Pandemic: Domestic Violence Surges During COVID-19.”

The stark reality was that movement restrictions and quarantines that were put in place to slow the spread of the virus made violence in homes more frequent and more dangerous. And many states had prematurely suspended or overspent their emergency ordinances, rolling back housing availability and protections, forcing families in shelters who were awaiting new apartments to hold out days, weeks, or months longer.

For Sarah Shuster ’12, who reached out to Flood to help after she saw Just Human’s Instagram posts, this provided an even greater urgency to aid women in transition.

“I had been doing a graduate social work internship working with a domestic violence counseling team that worked out of the Queens Family Justice Center, doing intakes, counseling, and support groups for survivors of domestic violence. I unfortunately saw firsthand, with the start of COVID-19, how difficult it was to reach so many of the clients I had been working with all year,” says Shuster. “As many of us were reading the news, I was seeing in person how much more unsafe our women, children, and families were becoming. If I was able to reach someone, it was because they were in their car or in their bathroom, and I was really resorting to having to email and text with so many of the women who were grieving that massive change.”

Shuster joined Flood and Hinkle for a “double setup” day over the summer, where the volunteers set up the apartments for families in Manhattan and in the Bronx. Apartment setups are held on weekends during times that work for the families and volunteers. Reeve Lanigan ’19 also has contributed to Just Human, organizing a large donation pickup in Pennsylvania. It’s the generosity of donors and volunteers that keep Just Human going.

“Another concern is that when eviction moratoria are lifted, it’s going to change the dynamic and the timeline of when people might move in and out of shelters, whether they’ll be able to find affordable housing, and what their vouchers cover. Certain vouchers only cover so much, and they often do not cover furnishing an entire apartment,” says Flood. “Especially in the New York and New Jersey area, families were waiting on housing vouchers to be processed, so the need was only growing.”

Despite the restrictions, Just Human was able to furnish apartments for several families over the summer, making sure that they followed social distancing and masking guidelines while also relying on a strong network of about 10 volunteers to help get everything set up.

“When we organize a setup day, we collect and curate the donations that kind of fit together and make sense,” says Flood. There is a form that collects information on the apartment layout and what furniture or decor is needed. “Then, based on what the family needs, we have our volunteers meet us that day to help do the heavy lifting, some light building, or put furniture together.”

Some of the women who are moving into their new apartments are the ones lending a helping hand. Others wait and come in for the first time with their children after everything is in place. The experience is usually an emotional one for all involved.

“I remember one woman who said, ‘I can’t believe this is my home. This looks like a home that somebody else lives in that I just get to visit,’” recalls Hinkle. “My favorite part of this setup was that we didn’t bring in that much new art. Instead, we framed artwork her grandchildren had made with crayons and taped onto her walls. We framed what mattered to her and her family.”

An Extended Network of Female Empowerment

In the U.S., female adults, youth, and children comprise 38% of those experiencing homelessness, with adult women and female youth making up 29%, or nearly one-third. While women with children are recognized as a distinct population with urgent needs, single women without children have remained the most invisible subgroup, only recently receiving formal recognition in the hope that their special needs will translate into specific and needed programming and funding.

It’s important to remember that not every woman facing homelessness comes from a domestic violence situation. Racism, poverty, gender inequalities, employment discrimination, and housing or food insecurities are all issues that women face that put them in a difficult situation. Whatever the reason for needing transitional housing, these women rely on an extended network of volunteers to connect them with those who can help them restart their lives.

One of those volunteers who connected Just Human with two women in need last year was Shemin Wilson, Bronx resident and founder of STARS & WINGS, a women’s empowerment program that rose from Wilson’s desire to show women that their collective strength is more powerful than the messages and environments that try to divide them. STARS stands for “Standing Tall and Respecting Self,” while WINGS stands for “Women in Need Gaining Strength.” The 12-week program focuses on financial literacy, self-esteem, and developing a support system.

“I do this for women in shelters and women in domestic violence situations, but my program is actually for all women and girls. Because we go through the same things, just at different times in our lives. So, who better to help a woman than a woman?” asks Wilson. “We’re here to learn from each other and serve each other.”

Several women Wilson referred to Just Human were able to move into their new accommodations last year, and Wilson is in the process now of continuing to look for places that might be suitable for more women to move this year.

“Getting apartments has been difficult, because some people are nervous about just going around to look at them. Some women become frustrated because apartments are not becoming available as quick as they should be,” Wilson says about the way the virus has slowed the housing process. “But, we just try to stay positive, and I remind them that when it’s their time, it’s their time. During the time we work together, we become family. I’m the person who believes for them.”

Plans for 2021

When the coronavirus began stalling collection of donations or ability to set up apartments, Flood and Hinkle moved all donated items into a storage facility and set up an Amazon Wish List (listed on Amazon under “Just Human Families”) for new linens, bedding, couch covers, and other essential items. Utilizing social media, they also put out word to their generous donors that they are in need of rent to cover their existing and additional storage units, as well as a bigger vehicle to pick up donations.

“Our intention is for folks to be able to partner with us, and maybe say, they want to create a fundraiser and cover rent for a storage unit that is their Just Human location in their area,” says Hinkle. “These types of services are needed everywhere and are not unique to our county. So, I’d hope we can help them connect with local domestic violence shelters and help raise funds and get donations for their community, as well.”

Unlike a designer who may come in and design based off of the spatial needs and lighting, we’re coming in and filling homes with what the family thinks a home should be filled with.

–April Hinkle

co-founder of Just Human

“We want everyone to know that throughout COVID-19, we’ve been really safe doing these setups, and we don’t accept any used linens or towels. Our Amazon Wish List is where all of those items are purchased new thanks to the generosity of our donors,” says Flood. “We have more and more generous people asking if they can donate all the time, but our units are full, and we’re really in need of more storage space.”

Flood and Hinkle would also like to recognize that Just Human collects donations from a diverse group of community members, and that their volunteers come from a variety of backgrounds ranging from concerned citizens, to professionals in the field of social work, and survivors of family violence.

“We’re very intentional about offering choice in not only how the setup is facilitated, but in aesthetics, as well. As two white women, we recognize that our design preferences are not reflective of everyone’s,” says Hinkle. “Unlike a designer who may come in and design based off of the spatial needs and lighting, we’re coming in and filling homes with what the family thinks a home should be filled with.”

Anyone who is interested in donating to Just Human can visit the website at justhuman.org