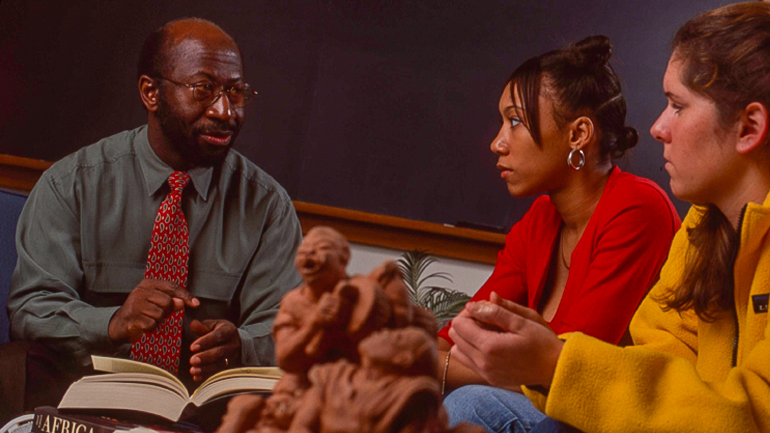

A servant-leader, Prof. Rexford Ahene reflects on his 40-year career

Rexford Ahene

Rexford Ahene made his decision to stay at Lafayette during his first day of class, despite a jarring, racially derogatory welcome.

“Half my class walked out when I introduced myself as a professor,” he recalls. “The students told me they didn’t come to Lafayette to be taught by a Black professor. It was shocking and unexpected, especially in 1982.

“I was also surprised to discover that I was the only tenure-track faculty of color on the entire campus,” says Ahene, professor of economics. “The only previous full-time Black professor was G. Earl Peace Jr. ’66, appointed professor of chemistry at Lafayette in 1971. These observations shattered my innocence and the image of serenity about the College, and became the clarion call to advocate for change.”

Ahene challenged the students and presented his credentials.

“If you want me to teach, then stay. If you don’t want this, go ahead and walk out,” he remembers saying. “The rest of the class stayed. So I taught the class.”

Shaken and angered by the experience, he walked directly to see David Ellis, president at the time, to explain what happened and share his disbelief that an institution such as Lafayette could be so racially intolerant.

“David Ellis immediately said, no, we want to change,” Ahene says. “I wanted to quit. Instead, he turned around and said, ‘Let’s be partners. Let’s see what we can do to change the institution.’ And that changed everything because suddenly it became a challenge. It became an opportunity rather than a detriment. And that’s what started this whole 40-year career.”

With perseverance never in short supply, Ahene went on to help found the McDonogh Network, became a faculty adviser to the Association of Black Collegians (ABC), chaired the Black Cultural Center Committee, and helped establish the Portlock Black Cultural Center, the Office for Intercultural Affairs, the Africana studies program, and the Interim Program/Study Abroad in Africa.

He also created the College’s dean for multicultural affairs and diversity issues position, helped establish the Black Coalition, an informal affinity group established to make Lafayette College a more welcoming place to work and learn, in 1994, and worked to recruit Black faculty through the creation of the Faculty Diversity Committee in 1983.

Far beyond Lafayette, he has left his mark internationally, serving as a policy adviser to many national governments, multilateral development institutions, academic institutions, and think tanks on how restructuring property and economic rights can enable markets and free enterprise to redress the ill effects of colonialism and underdevelopment, especially in post-colonial countries throughout Africa.

He is the principal architect and author of land policies in Tanzania, Malawi, and Sierra Leone, and the senior land policy adviser for Uganda and Liberia. Since 2006, Ahene has served as the senior technical adviser for designing and implementing digital land information systems for land administration reforms in Sub-Saharan Africa, work that has changed and improved lives.

Beginnings

At the start of his working life, Ahene, who grew up in Ghana, had no intention of seeking a career in academia or coming to the United States. He earned a bachelor’s degree in real estate and land economics from University of Science and Technology in Kumasi, Ghana, and took a job as an investment appraisal analyst for housing and construction at a bank. After hours, Ahene helped his uncle manage his hotel and bar.

“Life was very good,” he says. “You know, as a young man, managing a bar and having a job at a bank, what could be better?”

But his career trajectory changed when two professors from Virginia State University, a historically Black college, came to Ghana to conduct an economic analysis of small-scale farming and study property rights of farmers in Ghana. He was encouraged to join the research team.

“I flatly refused, because, you know, life was good,” he laughs.

But his father and the Virginia State faculty convinced him to become a research assistant for the project and travel to the United States with the team to finish the research, which led him to earn a master’s degree.

The offer, however, did not include a return ticket to Ghana. His parents did not have the money to bring him home, so he chose to continue his education in the United States, where he was granted citizenship, and earned his Ph.D. at University of Wisconsin, where he wrote his thesis on property rights, a topic that would become one of his lifelong passions.

“It’s something I’ve thought about a lot,” Ahene says. “On one hand, I’m sure I would have been very successful as a banker in real estate and probably would have had a very good career. But my contribution is exponentially larger, because of the opportunity to come to the United States.”

Lafayette’s Global View

“Lafayette provided the flexibility for me to be a teacher and a mentor to students on campus, but also the freedom to pursue my scholarship and professional career in Africa,” he adds, recalling his first land policy project in Tanzania in 1994 as the country was transitioning from socialism to a market-based economic system.

The Tanzanian government was going to cancel the project while Ahene was in the middle of a teaching semester. Sensing the importance of Ahene’s global influence, the provost at the time allowed him to turn his attention to the situation in Tanzania.

Professor Ahene and Jane Goodall

“I took 10 days off in the middle of the semester to go assess the situation, lay out a plan for moving forward, and gather a team together to continue to do the research,” he says. “And then the College gave me an unpaid leave for the next year, even though I wasn’t due for a sabbatical. I spent a year in Tanzania, leading the policy formulation process. Most academic institutions will not just allow a professor to get up and go do some project in Africa and not worry about it.”

As Ahene’s reputation in authoring and successfully executing land policies grew, Lafayette always afforded Ahene the time to carry out his important work that improved the lives of Africans in several nations. Land and land-based natural resources are fundamental resources for every country, and a national land policy expresses the aspirations of a nation on management of land resources, Ahene says.

“When I needed to spend longer periods of time in creating these policies, Lafayette was flexible enough to allow me to do that,” he says. “It allowed me to focus on doing my work, which is also why I owe so much of my success to the institution for helping me develop and grow professionally.”

His most recent work has involved finalizing the primary policy on land and natural resources in Sierra Leone and bringing the principles of participatory democracy and public policy to that country while helping to alleviate poverty and improve food security.

“Having Rex on board has been a great opportunity for Sierra Leone. His enormous experience and professional ethics are always admired among people,” says Samuel B. Mabikke, land tenure officer and head of the Natural Resources Unit of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

“Rex’s work went beyond policy formulation to actual practical implementation,” he notes. “Through his technical support, capacities of government ministry staff were increased on innovative fit for purpose land administration practices for securing community land rights.”

As a result of Ahene’s work, for the first time in Sierra Leone, families in more than 60 communities were able to receive their cadastral maps showing the actual land size and harmonized boundaries in four districts of Sierra Leone, Mabikke says.

Mentor, Friend

As he has helped improve lives in Africa, his roles as ABC adviser and as a creator of programs to help the underrepresented have been valuable resources for students of color or anyone in need of a friend and mentor to navigate the world of college life.

“As a minority faculty member on a predominantly white campus, I know about feeling isolated and unmoored during my early years at Lafayette,” he says. “Similarly, first-year students of color, African, and first-generation students often arrive on campus unfamiliar with a college’s academic and social pressures. They often perform poorly during their first year at Lafayette. Introducing students to how to relate to faculty, navigate advising, and pursue research or scholarship resources at Lafayette became a huge part of my role as a member of the faculty in the Economics Department and as ABC adviser.”

ALUMNI REMEMBER PROF. Ahene

Yolanda Wisher ’98 grew up watching the sitcom A Different World and dreamt of one day going to a college where, like the young hip college students on the show, she would find Black professors who understood her struggles and would challenge her to reach her full potential.

“I didn’t end up in a fictional or real HBCU, but I did find Prof. Rexford Ahene,” says Wisher, an established poet, musician, educator, and former poet laureate of Philadelphia.

“Sometime during my sophomore year at Lafayette, I decided to double major in English and Black studies, and he helped me to create a customized Black studies major that focused on my interests in communications,” she recalls. “An economics and Africana studies professor, he became a mentor to this poet and performer, encouraging me to take business and logic classes, coaching me through ruthless edits of my internship articles by news editors, and catching more than a few of my tears on his shoulder.”

Wisher describes Ahene as the kind of teacher who makes teachers.

“He lit a fire in me as a young college student and kept it burning. Kept in touch. Kept me in mind. Sang my praises long after I was gone. Embraced my husband as if he was also one of his students,” she says.

Wisher asks, rhetorically, what kind of teacher does that?

“A gifted one, a called one, a deeply loving one,” she responds. “When I think of what I know of Prof. Ahene’s life and how much he shared it with all of us at Lafayette, I am humbled to the core, and I am simply driven to be more than even he has seen in me. I am grateful for the love and light that he has poured into me and all of his students.”

Student concerns have always been close to Ahene’s heart, says former trustee Leroy D. Nunery II ’77, who worked with Ahene on the Portlock Center and the McDonogh Network.

“Over the years we had numerous conversations about student life and student success,” says Nunery. “Having that sense of belonging in an environment that’s not always the most comfortable or friendly has always been important to Rex. I always found conversations with him to be intellectually stimulating because his perspective was more global, and he could always understand the plight of African Americans.”

Ahene says his success at mentoring derives “from unpacking my background and personal experiences as a first-generation immigrant faculty of color.”

“I recall spending countless hours listening and paying attention to student concerns, recalling what it was like to navigate a new environment, and how to use that knowledge to guide students positively and constructively,” he says.

“Mentoring increases my job satisfaction. It allowed me to know students at the individual level, and often provided timely opportunities to listen and pay attention to student concerns, engage, and provide appropriate feedback,” Ahene adds. “As a role model, I enjoy empowering students to build confidence in their pursuit of professional opportunities in their chosen disciplines and achieve career goals.”

Ahene has been a loyal mentor to generations of students, administrators, and faculty colleagues, “a servant-leader in the strengthening and furtherance of the important mission of the College,” says Gladstone “Fluney” Hutchinson, associate professor of economics and policy studies and founder of Lafayette’s Economic Empowerment and Global Learning Project.

“Prof. Ahene’s contributions to our beloved Lafayette community have been significant and lasting in seen and unseen ways,” he says, from his work to develop the full promise of all Lafayette students to restructuring property and economic rights in post-colonial countries throughout Africa.

“His work is straightforward—fairness and justice in the ability of individuals and communities to own, utilize, enjoy, and profit from the exchange of their property, whether this property be intellectual, human, creative or physical, is essential to human and economic agency, wealth building, and prosperity, and constitutes a central pillar in any community-based or national development and progress,” Hutchinson says.