Diagnosing Dyslexia

by Adam Pitluk

On the outside, Lee Pesky was everything his father, Alan ’56, had been at the same age. Tall, handsome, and athletic. A chip-off-the-old-block, as it were.

But on the inside, Lee ’87 faced challenges his father never had. He had difficulty getting his thoughts down on paper, which made him struggle mightily with schoolwork. His teachers often scolded him for sloppy handwriting and poor note taking. These daily admonitions frustrated Lee, and by proxy his parents, who were concerned about the amount of effort their son expended to get so few results in school.

The situation came to a head when a third-grade teacher told the Peskys their son couldn’t do the quality of work expected of him and belonged in a special school for slower students.

“They were using code language to say Lee wasn’t very bright or mature, whatever you want to call it,” says Alan Pesky, an emeritus trustee at Lafayette.

“We ended up having Lee diagnosed by a neurologist who was able to decipher that Lee had a problem processing information.”

He also had a disorder called dysgraphia. “He was bright, but he had this small motor control problem so whenever he had to write, take a test, or do homework, he was at a very big disadvantage,” adds his dad.

In those days, a diagnosis was most of the battle, as the term “learning disability” didn’t enter public consciousness until the mid-1970s. In addition, special education didn’t become a protected category under federal law until 1975, and local boards were free to define and treat such students according to whichever parochial philosophy they saw fit.

Once Lee got the help he needed, he did his part by working his tail off, first to make it through middle and high school and then to get into a really good college: one named Lafayette. A chip off the old block, indeed.

After graduating in 1987, he moved to Idaho, where his parents were living, and started a chain of bagel stores. An entrepreneur at heart, he was just coming into his own when in 1995 he was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor after he blacked out behind the wheel of his car. Lee Pesky was just 30 years old when he passed away 10 weeks later.

“During that 2 ½ months, we lived a lifetime,” Pesky says. “When he took ill, we decided that we would do something to keep his memory alive. Nothing made greater sense than to do something for children dealing with learning disabilities in Lee’s honor.”

“There’s evidence to suggest that there is a difference in problem-solving ability for children with and without dyslexia, and that this ability correlates with certain candidate dyslexia susceptibility genes.”

– Lisa Gabel

In 1997, the Lee Pesky Learning Center opened in a strip mall in downtown Boise with two employees. Twenty years later, it has 32 employees and an annual budget exceeding $1.8 million. The center, by way of Alan Pesky, also works with Lafayette’s Lisa Gabel, associate professor of psychology and neuroscience, who is on the precipice of a scientific breakthrough that could save years of frustration and heartache for the millions of people who have difficulty making sense of language.

Armed with a virtual maze and joystick, Gabel, with the help of students, has developed what she says is an early-detection method for the propensity of a learning disability known as dyslexia. It has a prevalence of 5 to 17 percent in school-age children and makes it more difficult to process written, and sometimes spoken, language. Although the condition was first identified in 1881, only about five out of every 100 persons with dyslexia are diagnosed and receive treatment.

“We determined that the maze enabled us to successfully identify individuals with dyslexia,” says Gabel. “Our research with humans and animals was intended to determine if specific deficits are associated with certain genetic factors for dyslexia. There’s evidence to suggest that there is a difference in problem-solving ability for children with and without dyslexia, and that this ability correlates with certain candidate dyslexia susceptibility genes.”

Gabel’s work is still in progress, but her findings are starting to make some noise in scientific and neurological circles. “I can’t tell you that every dyslexic child will exhibit the same problem-solving strategies, but we tested over 150 children, and those who were reading impaired showed significantly poorer performance on this task than those who weren’t,” she says.

Her extensive research into finding a way to diagnose dyslexia before a student enters school has been going on for almost two decades, and began long before her son was diagnosed with it at age 6. She’s published numerous papers on the topic and has earned international recognition in the field. She’s currently an Alexander von Humboldt research fellow at the Friedrich-Alexander Universität in Germany. She is using her appointment to examine children from diverse language backgrounds to determine if impaired performance on this task is universal among children with reading impairment.

Alexandria Battison ’16 meets with Alan Pesky ’57 at the lab in Oechsle Hall.

BRAVE NEW WORLD

Alan Pesky also introduced Gabel to Evelyn Johnson, executive director of the Lee Pesky Learning Center, and the two educators have been working together ever since. In March, they presented their research at Oxford University before the British Dyslexia Association, which is the preeminent association in Europe for educating students, teachers, and the public about dyslexia.

Development of the maze began about four years ago in a basement lab in Oechsle Hall. After assessing how mice with gene mutations similar to those identified in dyslexic humans navigate

a maze for a food pellet, Gabel and her students developed an identical method that functions like an online computer game. Children use a joystick to motor their way through the network in search of a red ball.

“If a kid were to take longer to perform on the maze, it might indicate that he or she has a reading disorder and should get screening,” explains Alexandria Battison ’16, a Ph.D. candidate in neuroscience at University of Connecticut. “You learn to read and you read to learn, so often by the time children are diagnosed they’re struggling in all subjects.”

Battison and another one of Gabel’s students, Isabella Maita ’17, traveled to the Lee Pesky Center in February to facilitate testing of the online maze on a group of 5- and 6-year-olds. There’s a lot more that goes into conducting experiments on humans than collecting data from animals. “When you do stuff with kids you have to think through every aspect of design,” says Battison, who is not only attending Gabel’s alma mater, but working with her mentor. “Did I put the joystick on the right or left side? Can they see the screen OK? Are they getting fatigued or losing interest? Is the chair the right height?”

Afterward, the children provided saliva samples for DNA analysis by Dr. Jeffrey Gruen, professor of pediatrics, genetics, and investigative medicine at Yale University School of Medicine. The Pesky Center and Gabel are working in collaboration with the Gruen Lab to determine gene risk variants associated with the genetic susceptibility of dyslexia.

“Nothing made greater sense than to do something for children dealing with learning disabilities in Lee’s honor.”

– Alan Pesky ’57

It’s a brave new world when it comes to learning disabilities, and the Pesky Center, in partnership with Lafayette, is leading the charge. The only full-service facility of its kind in Idaho and the four neighboring states, the center is working with clinicians and researchers at Boise State University to stay abreast of all the latest teaching techniques and technology. It also helps educate teachers on how to instruct dyslexic students, which is not the same as providing tutoring.

“Tutoring is one thing, but intervention is different,” says Pesky. “Intervention is understanding the problem of a child and working around it. Tutoring is sitting there and not understanding the problem, but trying to bang it into the kid’s head on how to do it. We knew Lee had learning problems, but we weren’t able to give him the type of understanding and intervention they get today at the Lee Pesky Learning Center. We now understand what goes on in the mind of a child, and we give them the tools to succeed.”

Lee’s younger brother, Greg ’90, serves as vice chair of the center’s Board of Trustees, a role he relishes. “It’s such a personal focus for our family,” says Greg, who entered Lafayette as a freshman when Lee was a senior. “To my parents’ credit, they took the greatest tragedy that can happen to a parent and turned that pain into something extraordinary.”

In a similar way, Greg and his older sister, Heidi, channeled Lee’s entrepreneurial spirit to launch NEATGOODS, a company that brings function and design to everyday products for seniors. “Lee was probably more of a risk taker than me and my sister,” Greg says. “He really enjoyed life. He had a fantastic sense of humor. He followed his passion and heart.”

LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES

In addition to the scores of children and adolescents benefiting from the research of Gabel and the Lee Pesky Learning Center, there are some other beneficiaries: Lafayette students. Erin Murray ’19, a neuroscience major from Princeton, N.J., is staying on campus this summer so she can continue to work in Gabel’s lab, where she’s collecting control data from students on campus.

Then there’s Maita, a neuroscience major from Fair Haven, N.J., who took the advanced research course with Gabel solely because of the teacher. “I wanted to study under Dr. Gabel,” she says. They Skyped every Tuesday for an hour and a half while Gabel was in Germany. The course, she says, was career defining. “Dr. Gabel is an amazing professor. I knew she would be a great person to work with in the lab. She’s really involved, and we can talk like peers; but she’s a great role model for me or for anyone in her lab.”

Battison echoes that sentiment, saying her research with Gabel and the Pesky Center is not only the most memorable part of her college career, but the experience that shaped her most as a student and person. “I’m absolutely obsessed with Dr. Gabel’s research,” she says. “I love it. I want to keep working on it even in grad school.”

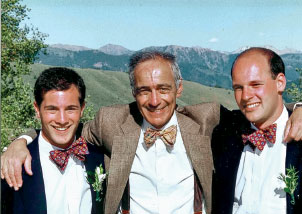

Greg ’90, Alan ’57, and Lee Pesky ’87 at their sister, Heidi’s wedding in Sun Valley, Idaho in 1993.

Pesky was traveling when Gabel’s students came to Idaho in February, so Battison didn’t get to meet the benefactor of her mentor’s research until he came to campus in May. The two hit it off. “I was immediately struck by how much passion he has for the work this lab is doing, and how invested and attentive he is to everything,” she says.

A self-described “overachiever,” Alan Pesky graduated from Lafayette with an ROTC commission and, after a successful stint in the military, received his MBA from Dartmouth College. In 1967 he and four business associates started their own advertising agency in a New York hotel room. Thirteen years later, they sold the business to Ogilvy & Mather, and Pesky stayed on as president to oversee its international expansion. When he stepped down in 1983, the agency had 15 offices around the world.

Now at 82, he’s the living embodiment of what Roman poet Juvenal articulated: “Mens sana in corpore sano,” which means “a sound mind in a sound body.” He still skis the expert trails at Sun Valley, Idaho, is training for his fourth New York City Marathon in 2017 to mark the 20th anniversary of the Lee Pesky Learning Center, and is hoping to write a book to inspire seniors to stay active. Alan Pesky and his wife, Wendy, also are involved in numerous philanthropic initiatives, including the Alan and Wendy Pesky Artist-in-Residence program they established in the 1970s at Lafayette.

But of all the journeys Alan Pesky has taken, founding the Lee Pesky Learning Center in 1997 has been the most rewarding. A few years ago, someone asked his wife what the Lee Pesky Center means to her. “She said it means that all children who come through our door can feel better about themselves and leave with a smile on their face and a little bit of Lee in them.”

You could say they’re a chip off the old block.

Lee’s block.

Adam Pitluk has dyslexia and vouches for the importance of early diagnosis of the learning disability.

For more information about the Lee Pesky Learning Center, go to: lplearningcenter.org

What is Dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a language-based learning disability. It is often experienced as difficulty in reading, spelling, writing, and pronouncing words. It is referred to as a learning disability because dyslexia can make it very difficult for a student to succeed academically in the typical instructional environment, and in its more severe forms, will qualify a student for special education, special accommodations, or extra support services.

What causes dyslexia?

The exact causes of dyslexia are still not completely clear, but anatomical and brain imagery studies show the neural system of the dyslexic brain processes written language differently than the “typical” brain. Dyslexia is not due to either lack of intelligence or desire to learn; with appropriate teaching methods, students with dyslexia can learn successfully. Many famous people are dyslexic including: Orlando Bloom, Whoopi Goldberg, and Stephen Spielberg. Albert Einstein was dyslexic.

How widespread is dyslexia?

Dyslexia occurs in at least five out of every 100 people, putting more than 700 million children and adults worldwide at risk of lifelong illiteracy and social exclusion. It’s estimated that 5 to 17 percent of school-age children are dyslexic in the U.S. Many go undiagnosed.

What are the effects of dyslexia?

The core difficulty is with word recognition and reading fluency, spelling, and writing. People with dyslexia also can have problems with spoken language and may find it difficult to express themselves clearly or to fully comprehend what others mean when they speak. Dyslexia also can affect a person’s self-image. Students with dyslexia often end up feeling “dumb” and less capable than they actually are. After experiencing a great deal of stress due to academic problems, students may become discouraged.

How is dyslexia treated?

Dyslexia is a lifelong condition. With proper help, many people with dyslexia can learn to read and write well. Early identification and treatment are key to helping individuals with dyslexia achieve in school and in life. Most people with dyslexia need help from a teacher, tutor, or therapist specially trained in using a multisensory, structured language approach. It is important for these individuals to be taught by a systematic and explicit method that involves several senses (hearing, seeing, touching) at the same time.

Source: International Dyslexia Association