Game Changer

Imagine the composer Leonard Bernstein in khaki shorts and a ball cap on a high school athletic field in Brooklyn. Instead of using a baton to divine a Beethoven sonata from his wind, wood, and brass sections, our Bernstein, AKA John Moser ’83, is using a wooden staff with a netted pocket to produce something just as melodious from a bunch of teenage boys learning the game of lacrosse.

“Sticks to the outside, sticks to the outside,” yells Moser, weaving between squat and lanky players alike who are shrouded in shoulder and chest pads, helmets, and thick gloves. “You’re bunching up, offense. Spread out. Now quick, quick.”

“You,” he calls to a defender in a white jersey with brown legs thin as Popsicle sticks. “Get on it.”

Welcome to CityLax Summer Camp where for two weeks in July roughly 45 boys and more than 90 girls are working on passing, scooping, cradling, and throwing a rubber lacrosse ball, essential skills in a sport that is among the fastest growing in the country, according to a recent Sport & Fitness Industry Association report.

But these kids aren’t your typical lacrosse players. There’s Caleb from Guyana, Constantine from Moldova, and Robert from the Dominican Republic.

Their parents didn’t pack their gym bags the night before, buy them Gatorade, or drop them off in an SUV. Most of them traveled more than an hour by subway to Frank J. Macchiarola High School, where donated gear was handed out in assembly-like fashion to new recruits who hail from 25 high schools in the city’s five boroughs.

The camp is a means to the end for CityLax, a nonprofit that uses lacrosse to teach life skills such as teamwork, discipline, and time management to students in underserved communities and schools. That’s what drew Moser to the field: the opportunity to use a sport he loves for a higher purpose.

“Lacrosse is just the vehicle,” says Moser, who was named CEO of CityLax in 2014 after spending more than a decade as a coach and board member. “Our real goal is to take what they learn on the field back to the classroom and put them on a path that leads to college.”

Getting Started

Lacrosse has long been a part of Moser’s life. He grew up attending games at his mother’s alma mater, William Smith College, a powerhouse in the collegiate lacrosse world. He first picked up a lacrosse stick in seventh grade and later played goalie for Madison High School in Madison, N.J., where he was an All-State player in 1977. He then went on to play goalie and faceoff midfield at Lafayette for the late Bill Lawson.

After graduating with a major in history, Moser moved to Manhattan in 1983 to work in the hospitality industry at luxury hotels and celebrity chef restaurants while continuing to play lacrosse for New York Athletic Club.

“There’s something about the sport that gets into people’s blood,” says Moser.

It’s not surprising then that his two sons caught the lacrosse bug, and in 2005 when they were 10 and 13 he signed them up for Doc’s NYC Lacrosse, the only youth program in the city at the time. Matt Levine co-founded it in 1996 to give his own children a chance to play lacrosse in the city as he had done growing up on Long Island. Like Moser, Levine had been a goalkeeper but for Williams College where he was co-captain and led the nation in saves in 1971.

The two men became fast friends, and when Levine started CityLax as a way to introduce underserved youth to the sport, Moser knew it was something he could get behind.

“I was always impressed by these students. They had the same love of lacrosse that my boys and I did, but they were doing it all on their own; their parents weren’t there,” he says. “Until then, my only impact was on my two boys, and they were getting older. Here was an opportunity to help a whole bunch of kids.”

Growing Strong

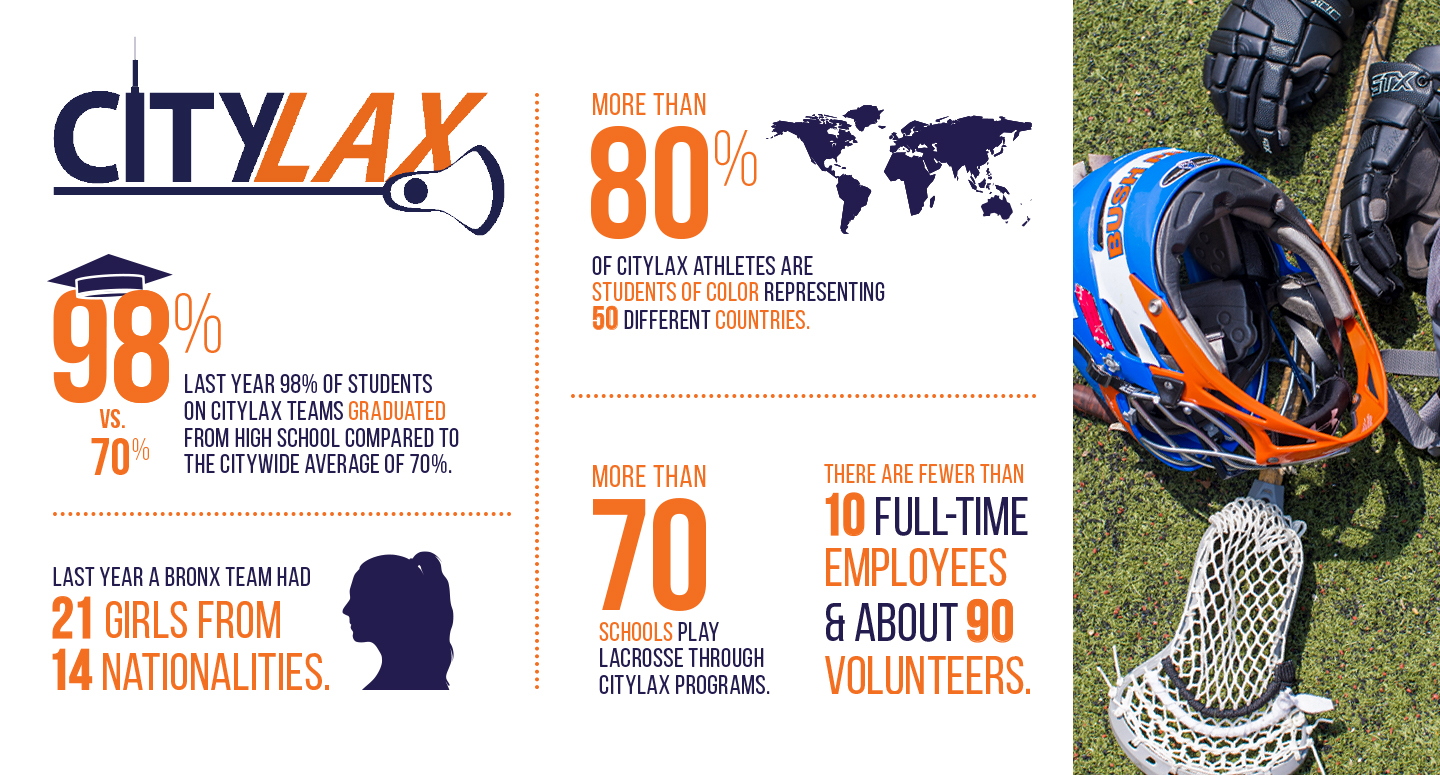

The first program was at A.P. Randolph High School in Harlem, and it took off from there. Today CityLax supports lacrosse programs at nearly 70 schools in New York City and Albany, N.Y. More than 2,500 boys and girls are in the program, and with fewer than 10 full-time employees, CityLax relies heavily on its roughly 90 volunteers to help develop new players, coaches, and teams.

“The growth has been incredible,” says Moser. “It’s a sport that appeals to youth because it’s gear-orientated, and it’s not a concussion sport. If you have a child who likes to run around and be physical, they’re probably not going to be severely injured.”

Being gear-orientated also can have a downside, as lower-income athletes don’t have the means for equipment and fees.

That’s where Moser comes in. As CEO, he focuses on raising funds to provide equipment and uniforms to schools at no cost. The nonprofit also picks up the tab for school insurance, transporting teams to and from games, training clinics, camps, and U.S. Lacrosse certifications for teachers who want to coach their school’s team. Under the rules of New York’s Public School Athletic League, head coaches must hold a valid teaching license with the Department of Education.

Not a lot of NYC public school teachers played lacrosse, so giving them the training they need to coach an unfamiliar sport is important, says Moser. However, it is not all about technique. Teaching life skills to the athletes is also a key component of the program.

“The great thing about sports is you need your teammates to win; you can’t do it by yourself,” says Moser, president of a hospitality consulting company and adjunct instructor at New York University. “It’s learning about sacrifice and the rewards of hard work.”

That message is apparently getting through. Last year 98% of students on CityLax teams graduated from high school compared to the citywide average of 70%.

“It not only keeps them in school but gives them pride,” Moser says. “Last year we had a Bronx team with 21 girls from 14 nationalities. One of them said, ‘We may speak different languages, but we all speak lacrosse.’”

Although lacrosse players still are predominantly middle- and upper-class white kids—in 2016, 85.9% of women and men’s college lacrosse players were white—CityLax is working to change that.

More than 80% of its athletes are students of color representing 50 different countries, Moser says, a virtual stick-wielding United Nations that is changing the racial and socio-economic makeup of the sport. As a result, it’s opening doors for minority athletes to access college and earn scholarships.

“One young lady who played for us while living in a car for two years got a four-year scholarship to Wagner College” in Staten Island, says Moser. “I talk to a lot of coaches who say they would love to get more integration on their teams. I know there is opportunity for these kids. Even if they don’t play, being on a team is a positive experience.”

While some CityLax players have received scholarships to play lacrosse in college, it mostly has been at Division III schools because it takes more than two or three years to master the skills needed to earn spots on DI teams.

For that reason, CityLax is focusing its programming in middle schools. “It’s a hard sport to get good at,” says Moser. “If these kids don’t pick up a stick until they’re a freshman in high school, it’s almost too late.”

There is another reason for starting kids early: grades.

“We have kids whose transcripts were terrible freshman and sophomore years,” says Moser. “They weren’t sure what they were doing. It wasn’t until their junior and senior years that the bell went off and they started to study. We kind of realized we have to turn the light on in eighth grade. If we can find ways to get them engaged earlier, I think we’re going to find more candidates going on to a Division I college.”

Like Lafayette. “That’s my goal,” says Moser. “I think the first CityLax student to come to Lafayette will be a girl. They’re catching up to the prep school players faster than the boys.”

Back at CityLax Summer Camp, 14-year-old David Waka, a hulking dark-haired midfielder, runs off the field glazed in sweat. This is the second year he’s attended CityLax Summer Camp after his mother pretty much forced him to attend last year, he says. “She found it on Facebook, and she was like ‘Why don’t you go? You can use your brother’s equipment.’” Waka started playing and recently earned a spot on his Brooklyn high school’s lacrosse team.

“When you have a team, it’s like a brotherhood, and you respect them and they respect you,” he says. “I didn’t really have that before.”

As the second day of camp ends, Moser heads home to Manhattan, his polo steeped in sweat and ears slightly pink from sunburn. He couldn’t be happier.

“I love doing this,” he says. “I feel like I owe the world back for all of the good things that have happened to me. The fact that I can use something I’m passionate about to help others, well, that’s a pretty fulfilling day.”